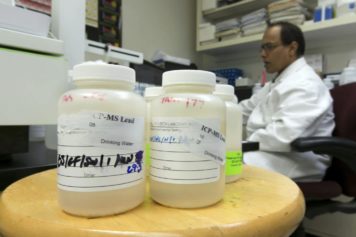

On June 2, President Barack Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency ruled that coal-fire power plants must reduce their carbon dioxide emissions by as much as 30 percent over the next 15 years. These plants are partially responsible for severe pollution, chronic health diseases and global warming, and they are disproportionately near Black communities.

As reported in the 2012 NAACP-sponsored study, Coal Blooded: Putting Profits Before People, more than three-quarters of African-Americans live within 30 miles of these plants.

The EPA ruling was slammed by conservatives, the right-wing media, and the fossil fuel lobby. As predicted, these groups said the proposal infringes upon the free market and is yet another example of Obama’s authoritarian impulses. Yet if the regulation leads to a dramatic reduction in pollution, improves the health of residents living near power plants, and encourages a greater reliance on renewable energy sources, then it may very well be a victory for progressive Black politics.

The contemporary roots of the EPA decision can be traced to Obama’s attempt to pass a climate change bill (the Waxman-Markey “cap-and-trade” legislation) in the early months of his presidency. The bill was a modest approach to curbing pollution and clearly written to win bipartisan support in Congress. Though some progressive environmentalists criticized the policy for being too lenient on the nation’s largest polluters, if enacted, the bill would have established the most far-reaching regulatory limits on greenhouse gas emissions.

Civil rights groups, Black lawmakers, antipoverty and environmental justice activists, and some labor unions—representing what some political observers referred to as the Climate Justice Movement (CJM)—worked closed with EPA Administrator, Lisa P. Jackson, the first African-American to hold the position, to shape the national climate policy. In contrast to mainstream (and mostly white) environmentalists, CJM groups incorporated concerns about racial justice, gainful employment, equitable land-use policy, and public health into the broader debate about climate change regulation.

In June 2009, the Waxman-Markey bill was approved by the U.S. House of Representatives by a seven-vote margin. Yet after the legislative battle, Obama immediately pivoted to health care and delayed a vote in the Senate. When the Senate took up the measure in the Spring 2010, just a month after the adoption of the health care law, it was dead on arrival. Conservative lawmakers and right-wing media worked hand-in-hand with the fossil-fuel lobby to frighten moderate Republicans and conservative Democrats into opposing the bill.

This overview is an important reminder of how instrumental Black activists have been in shaping the national dialogue over climate change, and that their influence was especially felt during in the initial months of the Obama presidency. The NAACP, the Congressional Black Caucus, and the U.S. Conference of Black Mayors all endorsed climate change legislation during this period. The Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, the nation’s most prominent African-American think tank, also formed an 18-member Commission to Engage African-Americans on Climate Change in 2008.

African-American and other CJM activists were actually involved in the climate debate before Obama’s election. In 2007, they pressured congressional allies to include a green jobs amendment in the Energy Independence and Security Act. The law created a workforce development program in green industries for people with barriers to employment (formerly incarcerated persons, transitional housing and homeless residents, low-income women, underemployed workers).

They also lobbied state and local officials to use the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant program to fund green jobs initiatives for low-skilled workers. By 2011, these two programs helped to bolster green jobs initiatives for working-poor residents in over 40 counties across the country.

Shortly before Obama’s election victory, CJM activists organized the “Dream Reborn” gathering in Memphis, Tennessee. Spearheaded by the Green For All organization, the event was held during the 40th observance of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. The hundreds of activists in attendance examined the intersection between civil rights and environmental equity. They also crafted community-based and policy responses to climate change. Several years later, Green For All created an outreach program for HBCU students interested in becoming climate justice activists.

Other groups shaping the national dialogue over climate change were the Climate Equity Alliance, Sustainable South Bronx, PolicyLink, the Apollo Alliance, and the Strategic Concepts in Organizing and Policy Education. The Hip Hop Caucus organized the Green the Block campaign for urban communities, even garnering support from federal agencies such as the EPA, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The Emerald Cities Collaborative also formed partnerships with 10 cities to help craft equity-based, sustainable development initiatives. Some of these groups sent delegates to the United Nation’s climate change conferences (officially called the Kyoto Protocols) to help negotiate an international climate agreement.

As the country debates the EPA’s legal authority to regulate pollution-emitting industries, we should remember that Blacks (and Black-influenced social movements) have been central to the debate about climate change. Although white liberals and environmentalists dominate the public narrative—they are typically guests on cable news and have cornered the market on climate change documentary films—Blacks have been at the forefront of explaining the relationship between climate change, racial justice, and poverty.

By: Sekou Franklin, Ph.D.