As expected, the U.S. Supreme Court today ruled that Michigan’s voter initiative banning racial preferences in admissions to the state’s public universities was constitutionally permissible, putting yet another nail in the affirmative action coffin.

“This case is not about how the debate about racial preferences should be resolved,” Justice Anthony M. Kennedy wrote in a controlling opinion joined by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., and Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. “It is about who may resolve it. There is no authority in the Constitution of the United States or in this court’s precedents for the judiciary to set aside Michigan laws that commit this policy determination to the voters.”

But in an impassioned reading of a summary from her 58-page dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor — who was joined in the 6-2 ruling by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, with liberal Justice Elena Kagan recusing herself— said the decision creates “a two-tiered system of political change” by requiring only race-based proposals to surmount the state Constitution, while all other proposals can go to school boards.

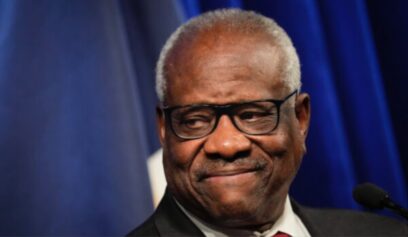

Sotomayor—who conceded she was the beneficiary of affirmative action, as has Justice Clarence Thomas, who was part of the majority—said that as a result of the ruling, minority enrollment will decline at Michigan’s public universities, just as it has in California and elsewhere.

“The numbers do not lie,” she said.

Indeed, since the ban was approved by voters, African-American enrollment at the University of Michigan has plummeted nearly 40 percent, from 6.4 percent of the university’s freshman class (not including international students) to 3.9 percent last year. At the prestigious University of Michigan Law School, this fall there were just 14 African-Americans among the 315 students admitted, a paltry 4.4 percent.

In contrast, Michigan’s Black population stands at 14.2 percent. Detroit, which is just a 45-minute drive from Ann Arbor, is nearly 85 percent Black.

The same drop-off has been seen in Blacks and Latinos at universities in California and Texas because of the race bans.

The Michigan case was not a clear-cut consideration of the merits of affirmative action; rather it was a somewhat murky legal skirmish between defenders of affirmative action and the Michigan attorney general, who had to defend the ban passed by voters seven years ago.

After the voters of Michigan, in a measure called Proposition 2, banned all “preferential treatment” based on race in education, it was struck down by the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. In an 8-7 decision, the appeals court said the ban violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution’s 14th Amendment because it presents an extraordinary burden to affirmative action supporters who would have to mount their own long, expensive campaign to repeal the constitutional provision.

That burden “undermines the Equal Protection Clause’s guarantee that all citizens ought to have equal access to the tools of political change,” Judge R. Guy Cole Jr. wrote for the majority on the appeals court.

The appeals court decision concluded that when the governing boards at the University of Michigan, Michigan State University and other public colleges set admissions policies at the schools and decide what factors they would use in determining admissions, groups representing athletes or alumni or musicians or any other grouping of students had the ability to lobby the governing boards on behalf of their students.

But proponents of affirmative action would have to change the state constitution to change admissions policy, which the appeals court ruled was an extraordinary burden.