Jamaica has had a rich history of creative resistance during slavery. Similarly, during the post-slavery era, many Jamaicans have played pioneering roles in the development and the advancement of Black consciousness ideas and movement.

Before and after 1776, Jamaica had an active trade relationship with North America. Port Antonio was one of those active trading ports; it was the setting in which John Brown Russwurm’s father, a white American businessman, lived.

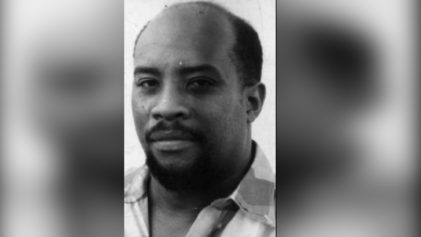

Winston James (2010) in The Struggles of John Brown Russwurm, 1799 to 1851, writes about Russwurm’s birth to a Black woman and his journey with his father to the U.S., where he attended school. The writer notes that at the time of his graduation from Bowdoin College, Russwurm may have been one of the earliest Blacks to graduate from a tertiary institution in America.

James notes that it was during his years in college that Russwurm began writing about Black struggles. Inspired by the Haitian Revolution and subsequent Black republic, he made it his duty to defend the young regime against propaganda depicting the Haitian people as savages.

Russwurm moved to New York after graduation. There he developed and published his ideas instilling greatness in racial pride and the back-to-Africa message. He emerged during the earlier period, before another early Pan-Africanist and back-to-Africa advocate, Edward Wilmot Blyden (1823-1912).

Russwurm met Samuel Cornish, a fellow African-American, in New York during the 1820s. They established Freedom’s Journal, the first newspaper to be owned and operated by Blacks in the U.S. According to James, the editors announced in their opening statement of the Journal that “we wish to plead our own cause, for too long have others spoken for us.”

Russwurm saw the paper as an “organizing force” among unorganized Blacks in America, aiming to “awaken African-Americans from the lethargy years.”

Russwurm’s writings advocated the role of family and the cultivation and growth of industry among Blacks by way of education and training. He saw education as that driving force towards higher achievements in science. He guided Black people in America along the path of race consciousness through which they could become useful and responsible citizens.

Eventually, he became disillusioned with America and went to live in Liberia, where he was established as a governor of that new Republic. A few years after his death, in 1851, and in one of the neighboring parishes to Portland, the Paul Bogle movement advanced Black consciousness struggles in another context in Morant Bay in St. Thomas Parish.

During the 1850s, the systematic program of land deprivation among the Black masses continued; the setting in St. Thomas Parish and all Jamaica was characterized by high taxation, high unemployment, high prices for basic food stuff, and severe and oppressive injustice.

The clarion call for “skin for skin” and Black unity was condensed into an assault against the agents of the planter and colonial power relations in St. Thomas. This violent insurgency of 1865 may have inspired a new thrust of Black consciousness among a few emerging Black intellectuals: Dr. Robert Love (a Bahamian who resided in Jamaica) and Dr T. E. S. Scholes. Both thinkers noted the role of the colonial-planter society and its systematic deprivation of the Black masses’ access to land.

They saw this as a deliberate strategy to keep Blacks and the country underdeveloped. Gordon K Lewis (1968) in The Growth of the Modern West Indies, describes Love as the publisher of the old Jamaican Advocate newspaper calling for Black representation in the Legislative Council, as well as, advocacy of Black consciousness.

According to Lewis, Love lived in Haiti, where he encountered ‘negritude’ and Black political representation. In the book, The Jamaican People 1880-1902 Race, Class and Social Control, Patrick Bryan (2000) describes Love, an Anglican pastor, as a secular-pragmatist; and Scholes, a Baptist, as another secular intellectual, and that they expressed their concerns about the land for the ex-slaves of Jamaica.

Bryan writes that Scholes placed the question of land tenure in the broader context of the imperial system of the appropriation of “native resources,” and he believed that it was a conspiracy by the British Empire to systematically deprive the Black masses access to land in Jamaica.

Noting the endless sources of laborers among the Black masses, Bryan writes that Scholes spoke about the high rate of taxation, land hunger, and the ignorance of scientific agriculture as hindrances to the development of the Black masses and the country.

Read the full story at the jamaicaobserver.com