For more than a century, the state of Florida operated a reform school for boys that led to the deaths of almost 100 boys, mostly Black, many of who were then buried in unmarked graves on school grounds.

The Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys in the Panhandle town of Marianna also left hundreds of survivors traumatized from the physical, mental and sexual abuse they endured while incarcerated at the school.

This year, more than 800 survivors will receive $20 million in restitution to be divided equally among them, according to CNN. That would amount to about $25,000 each, which is not nearly enough to make up for the abuse, according to one survivor.

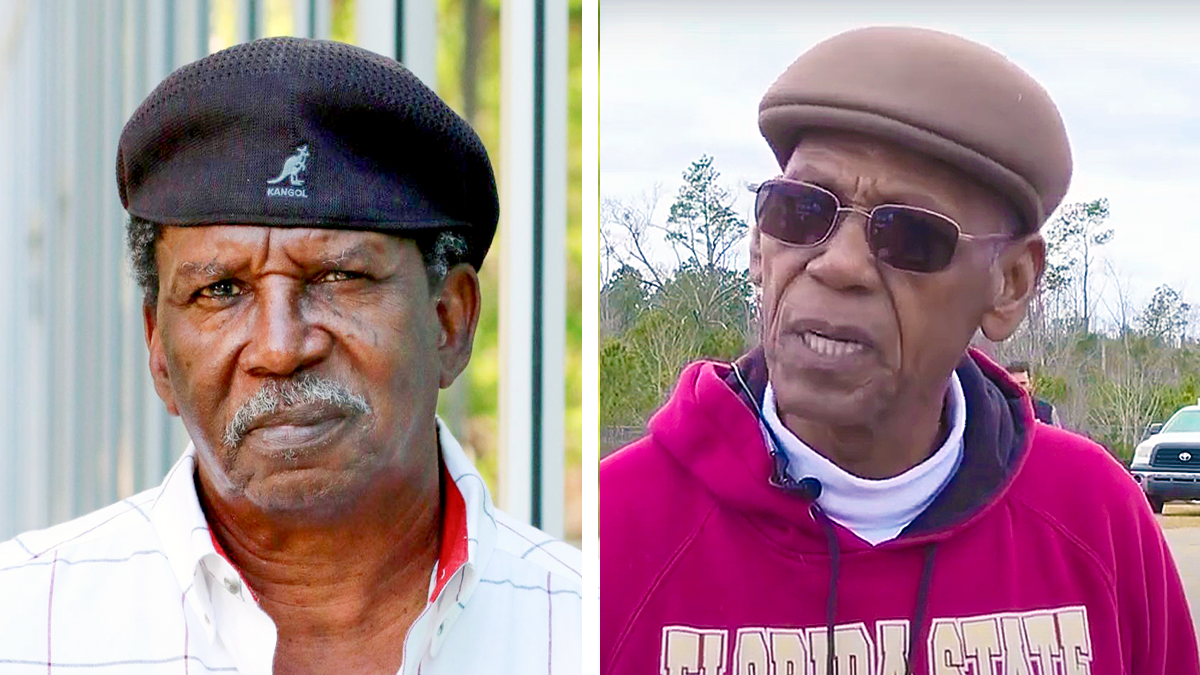

“It’s not enough money to pay a person for what we went through,” Richard Huntly, a 78-year-old Black man, told WESH in September when Florida legislators were finalizing the total amount to be paid out, going from $40 million to $20 million.

Huntly, who was sentenced to the school from 1957 to 1959, has published a book on his ordeals titled “I Survived Dozier: The Deadliest Reform School in America.”

Another Black man, Cecil Gardner, who is in his 70s, said he was raped as well as beaten on several occasions, including one time for speaking to a white boy in the institution, which remained segregated until 1966.

“I was beaten until the flesh was torn from my backside. … Beaten, for what? For nothing,” Gardner said in an interview with WUSF last year.

“Not only that, 12:45 one night, I can remember just like it was yesterday … [he] took me down to the White House and raped me. At 14 years old. … I’ve been living this day in and day out. How can grown men be put in a position to take care of young children, to rehabilitate them, and yet they end up abusing them?”

The abuse against Black boys was highlighted in the 2024 movie directed by a Black man named RaMell Ross titled “Nickel Boys,” which was based on the 2019 book by the same name written by Black author Colson Whitehead, who earned a Pulitzer Prize for the book in 2020.

Although a 2012 investigative report by the University of South Florida states that the majority of boys sentenced to the school for crimes like “truancy” and “incorrigibility” who ended up dead were Black, white boys were also beaten and sexually abused and left traumatized.

“I’ve seen a lot in my lifetime,” said Bryant Middleton, a white man in his 70s who was sentenced to the school from 1959 to 1961 and said he was molested by a school psychiatrist and also beaten several times, including for mispronouncing a teacher’s name, according to CNN.

“A lot of brutality, a lot of horror, a lot of death,” said Middleton, who served more than 20 years in the Army, including combat in Vietnam. “I would rather be sent back into the jungles of Vietnam than to spend one single day at the Florida School for Boys.”

Jim Crow Laws

The Florida State Reform School first opened in 1900 during the height of the Jim Crow era, where Black people were defined by law as second-class citizens and were forced to operate under a different set of laws than white people like “vagrancy,” resulting in many Black boys being sentenced to the school where they were then leased out to local companies and forced to work without pay.

“It was kind of like slavery,” said Huntly, who was 11 years old when he was first sentenced to the reform school in 1957, according to the Equal Justice Initiative.

Huntly also said that white boys were given vocational work while Black boys were made to work in the field picking and planting for state profit.

Investigations into allegations of abuse began as early as 1903 when it was reported that boys as young as 5 years old were being restrained with chains and irons as well as being leased out for labor, according to the 2012 report by USF.

“Throughout its history, the majority of boys at the institution were African Americans,” states the USF report. “Overall, there were more African American boys who died, and among those, they tended to be younger in age.”

One case described in the report is about a Black boy named George Grissom, who was 6 years old when he was sentenced to school in 1917 along with his 8-year-old brother, Ernst, for “delinquency.”

The two brothers were ordered to remain in the school until they turned 21 years old, but George Grissom died 16 months into his sentence under mysterious circumstances after he was leased out to work for free and returned to the school “unconscious.” The report states his burial location is unknown, as well as whatever happened to his older brother, who was only listed as “not here” in a document dated March 30, 1919.

However, the reform school was allowed to continue operating for more than a century despite several investigations and lawsuits over the years, remaining segregated until 1966, two years after the Civil Rights Act prohibited segregation.

It was not until 2008, years after a group of survivors began speaking out against their ordeals, that state officials finally apologized for the state-sanctioned abuse against children.

The school was shut down in 2011 after an investigation by the United States Department of Justice determined there was a pattern of abuse and unconstitutional conduct, including:

- Failure to adequately protect youth from harm;

- Unconstitutional uses of disciplinary confinement;

- Deliberate indifference to youth at risk of self-injurious and suicidal behaviors;

- Violations of youth’s due process rights; and

- Failure to provide necessary rehabilitation services

In 2012, Erin Kimmerle, a forensic anthropologist and University of South Florida associate professor, led a team of anthropologists, archaeologists and biologists to search for unmarked graves at the school in a state-approved project.

The researchers searched through archived documents from the school and discovered 96 children between the ages of 6 and 18 died at the school between 1914 to 1973.

They also discovered 50 graves around the reform school but believe there are many more unmarked graves.

“It is possible that additional graves and/or burial areas are present given the practice of segregation and number of cases that are still unaccounted,” the report states.

“Recommendations for further research and preservation of the site are also discussed for recognizing the historical significance of human and civil rights issues in Florida in the area of juvenile justice and the rights of families to have accountability and transparency as important aspects of restorative justice.

“These violations were the result of the state’s failed system of oversight and accountability. To protect the youth in its remaining facilities, the state must take immediate measures to assess the full extent of its failed oversight with the assistance of experts in juvenile protection from harm issues. The state must also strengthen its oversight processes by implementing a more rigorous system of hiring, training and accountability.”

The compensation is a result of legislation sponsored by Black Florida Sen. Darryl Rouson, who fought for years to get it passed before it was finally approved last year during his last term due to term limits.

Rouson, a Democrat, described the legislation last year to Florida media as “bittersweet.”

“Sweet, because the Senate leadership has put some funding behind this bill for the first time in years,” he said. “Bitter, because it’s a reminder and a retelling of the stories of the horrors that occurred there, that should never happen again.”