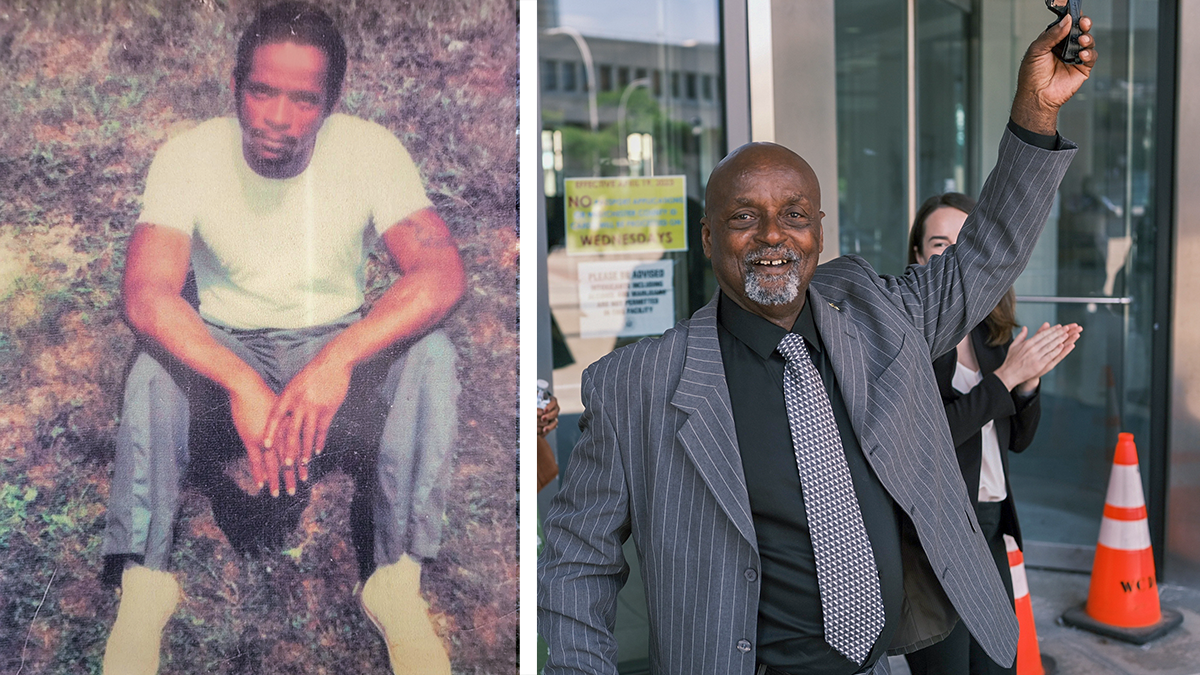

Leonard Mack was a 23-year-old decorated Vietnam veteran when he was pulled over by a cop in New York in 1975 and accused of rape.

Despite alibis and a blood test from the victim that proved his innocence, the Black man was falsely convicted, spending almost eight years in prison before he was released on parole in 1982.

He then spent more than 40 years living under the stigma of being a convicted rapist, resulting in a reduced pension from the military in addition to missed job opportunities. But he never gave up hope on proving his innocence.

In 2023, DNA evidence proved the actual rapist was another Black man named Robert Goods – who has been convicted twice on rape charges, including a rape that took place weeks after the initial rape. A judge then vacated Mack’s conviction that same year, ending his 47-year nightmare, believed to be the longest conviction overturned by DNA evidence.

On Tuesday, Mack, who is now a 73-year-old ordained deacon living in South Carolina with his wife of 21 years, filed a lawsuit against the Westchester County Department of Public Safety, the Greenburgh Police Department and the estates of several of the now-deceased investigators who implicated him.

The lawsuit, filed by the New York law firm Neufeld Scheck Brustin Hoffmann & Freudenberger, LLP, accuses the defendants of fabricating evidence, malicious prosecution and violating his civil rights.

“Mr. Mack’s conviction was the product of overt racism and forensic fraud,” said Emma Freudenberger in a statement, one of the lawyers representing Mack in his lawsuit.

“The police who framed him and the county’s crime lab analyst that stood in the way of the truth, must now answer for their actions—as must the agencies that employed them.”

The lawsuit states that “Mr. Mack was only prosecuted and convicted based on misconduct by Defendants.”

“Mr. Mack should have never been prosecuted, let alone convicted, as his innocence was apparent from the beginning,” the claim states.

“He did not look like the true assailant Robert Goods, had no interactions with the victims, had a corroborated alibi for the time of the crime and was excluded by serological evidence as the rapist before trial.”

The Incident

On May 22, 1975, two Black teenage girls were walking home from school in Greenburgh, a town in Westchester County about a 90 minute drive north of New York City, when a Black man forced them into the woods at gunpoint, binding their hands and feet and placing a blindfold over their eyes.

Goods then raped one of the girls identified only as S.F. in the lawsuit and attempted to rape the other girl identified as W.J. but the second girl was on her period, so he raped S.F. once again.

Goods then fled the scene, leaving the girls blindfolded with their hands and feet bound in the woods who managed to free themselves and call police police to report the rape.

The girls described the rapist to police as a Black man wearing a large black hat, a tan jacket and dark-colored pants as well as a gold earring on his ear. At 4:40 p.m., a dispatcher advised officers to be on the lookout for a Black man fitting the description of the rapist.

Two hours after the rape, James Fleming, an officer with the Westchester County Department of Public Safety, spotted Mack driving on the Bronx River Parkway and pulled him over, telling him he matched the description of a rapist.

But the lawsuit states that not only was Mack wearing clothes that did not fit the description of the rapist, he had spent the day with his girlfriend and her two friends and had also stopped at a local mechanic shop where he spoke to two mechanics.

However, Mack was wearing a gold earring and was also in possession of a .22 caliber handgun, so he was arrested for gun possession.

Investigators then pressured the girls to identify Mack as the rapist by conducting “a series of highly suggestive identification procedures with S.F. and W.J. designed to induce them to identify Mr. Mack as their attacker,” the lawsuit states.

“It was only as a result of Defendants’ improper suggestion that W.J. and S.F. ever wrongly identified the innocent Mr. Mack as their assailant.”

Police continued to implicate Mack despite his alibis, including his girlfriend, her two friends and the two mechanics, confirming he had spent the afternoon with them while the girls were getting raped at gunpoint.

Although DNA technology was not available at the time which would confirm without a doubt the actual rapist, investigators used a serology blood test that was able to confirm that Mack was not the rapist because the blood recovered from the victim did not match Mack’s blood type.

But investigators continued to implicate Mack in the rape, the lawsuit states.

Marie Felgenhauer, the Westchester County Labs analyst, conducted conventional serological testing on the underwear collected from S.F. after the rape. This testing excluded Mr. Mack as the source of the semen left by the rapist—and should have ended the prosecution before the trial.

But Felgenhauer fabricated that her serology testing demonstrated that Mr. Mack could have been the source of the semen in S.F.’s underwear, even though as she understood her own testing and basic principles of the field demonstrated he was definitively excluded as the source. Felgenhauer provided this fabricated serological evidence to the prosecutor and then at trial.

Relying primarily on this fabricated evidence and the highly unreliable in-court identifications of Mr. Mack from W.J. and S.F., the prosecution secured his wrongful conviction on March 29, 1976.

Mack was sentenced to seven-and-a-half to 15 years in prison where he spent his time writing appeals in the hopes of getting his conviction overturned.

DNA Test

Mack’s pleas for help reached the Innocence Project, a nonprofit organization that has helped free more than 250 wrongly convicted prisoners through DNA evidence.

In July 2023, the Innocence Project working with the Conviction Review Unit of the Office of the District Attorney for Westchester County confirmed through DNA evidence that the actual rapist was Goods who confessed to the rape when questioned by investigators.

A judge vacated Mack’s conviction in September 2023, finally proving his innocence which he had maintained for more than 40 years.

“The sole evidence implicating Mr. Mack was the product of Defendants’ unconstitutional misconduct,” the lawsuit states. “Based on evidence Defendants fabricated and their misrepresentations, Mr. Mack was wrongly prosecuted.”

Although Mack is now free, he knows there are many more people like him who are sitting in prison after being wrongfully convicted by malicious prosecutors and investigators.

“Sometimes I’ll be driving alone and I just start crying. And then I think about the other men and women sitting in prison right now who told people they didn’t do this. They’re innocent. I want to be able to do whatever I can to help these people, because I have experienced it,” Mack was quoted as saying in an article published by the Innocence Project.