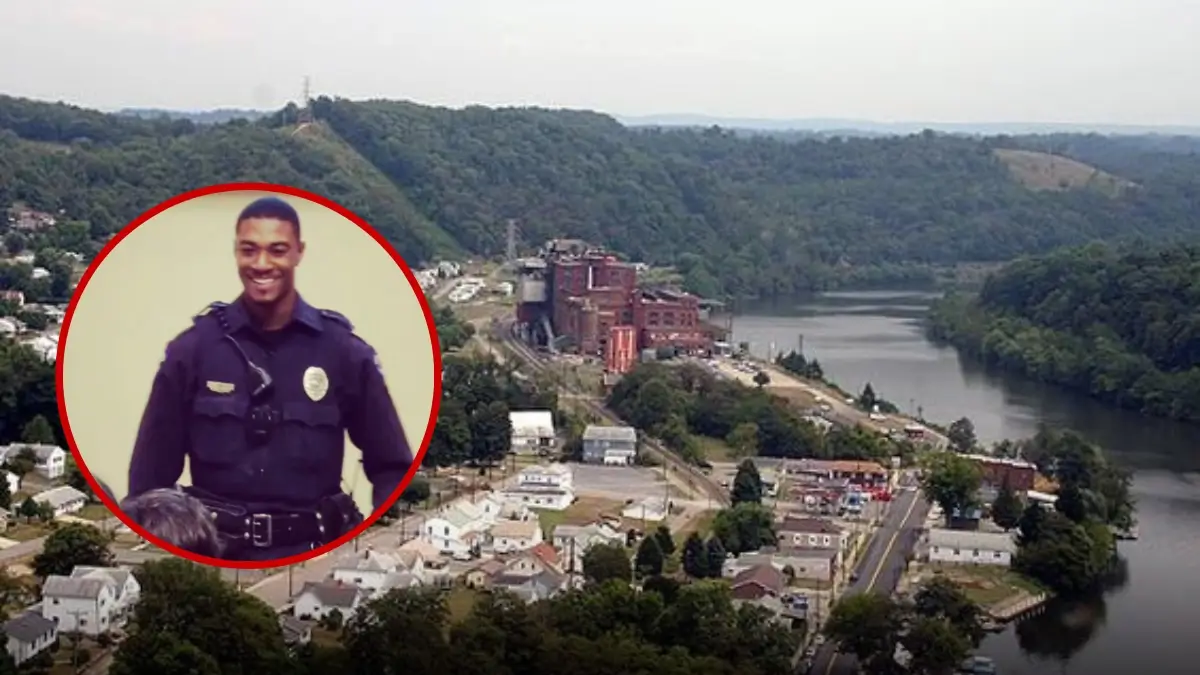

Lamon Simpson, 31, took the job in the mostly white Town of Rivesville, population 830, in September 2021, becoming the town’s first full-time police chief and, at the time, its only police officer.

Early on, town officials lauded his performance. Councilman Frank Moore “spoke approvingly of Simpson” at a town meeting in February of 2022, reported the Times West Virginian.

“He’s displayed that he really wants to be a member of this community, Moore said. “He’s making an effort, visiting schools, he’s out talking to kids and he’s doing a good job. Being a police officer today is not easy.”

But things soon turned sour between Simpson and town officials.

In a conversation with Mayor Barbara Beatty at the town hall, she “indicated to Officer Simpson … that if he could not handle being called the ‘N-word,’ he should reconsider his position because he was going to hear this term during his employment,” his complaint against Rivesville filed in Marion County Circuit Court in June alleges.

As he continued in his position, more discriminatory comments were made by town officials. His complaint states that in Simpson’s presence, Rivesville Town Council Member Michelle Bradley told the mayor, “I wish we could go back to the way policing was done in the 1960s,” comments the lawsuit argues “sought a return to the 1960s era in which African-Americans were assaulted and otherwise discriminated against by police.”

In February of 2022, Simpson received a call on his work cellphone. The unidentified caller “remarked along the lines of: ‘Is this the n*gger Chief? This means war!” the complaint alleges.

Simpson filed a report with the West Virginia State Police about the incident. When he began parking his cruiser and personal vehicle in the local garage instead of the street, out of fear that the vehicles would be vandalized, he told the mayor that the “racially threatening call” was the reason.

“In response, Mayor Beatty merely responded ‘Oh, ok,” and did not inquire further or take any action,” the lawsuit alleges.

Tensions in the Rivesville town hall were ratcheted up after an incident in May of 2022 when Simpson initiated a traffic stop on the mother of the Rivesville town clerk, Erica Corwin.

The complaint states that the woman was sitting in an SUV illegally parked in the street outside of an abandoned house suspected of drug activity, and that Simpson observed a man walking from her car to the house. When he approached and asked her for her ID, the man “became belligerent and yelled ‘you don’t have to talk to him,’ and ‘you are harassing us.’” Simpson recognized the man as Joshua Wolfe, a person suspected of drug activity by state police.

Simpson issued a warning to the female driver and permitted both her and Mr. Wolfe to leave the scene. A few days later, at the town hall, he says Corwin complained about him pulling over her mother, telling him “she didn’t feel comfortable working with him if he was going to be ‘stopping her family.’”

Later that day, Simpson informed a town council member and the mayor about the conversation with Corwin. “Mayor Beatty indicated that Rivesville did not want to lose a ‘good worker’ such as Clerk Corwin,” the complaint states. “Officer Simpson indicated in response that he did not desire that Clerk Corwin lose her job, but that he felt obligated to report the events in question.”

In June 2022, Corwin texted Simpson to indicate she was submitting her two-week notice to resign from her job with the town of Rivesville.

On July 6, 2022, Simpson was fired. Two town councilmen greeted him at the town hall with a letter stating, “’You are being terminated and your services are no longer needed,’” the complaint states. “When asked the reason for his termination, Officer Simpson was told a reason did not need to be provided.”

Corwin, who is white, remained employed at that time, the suit alleges.

Simpson was wrongfully fired in retaliation for “rightfully taking action in response to conduct exhibited by the family member of Defendant’s Town official Clerk Corwin,” the lawsuit contends, and was further “subjected to a series of adverse actions designed to undermine his career and professional standing.” The pattern of conduct violates the West Virginia Whistleblower Law, the complaint states.

Simpson also accuses the town of Rivesville of disparate treatment, discrimination and wrongful termination based on race in violation of the West Virginia Human Rights Act; a hostile work environment based on race; defamation; tortious interference with a business relationship and intentional infliction of emotional distress.

The civil rights violations in the complaint stem from how Simpson was treated by town officials and employees throughout his tenure as police chief and after he was fired.

Among other instances of alleged disparate treatment and racial discrimination detailed in the complaint, a member of the Rivesville Fire Department told Simpson that “Rivesville town council members, employees and/or citizens were accusing him of being ‘a racist cop who only pulls over and targets white people.’”

The complaint notes that according to the American Census Survey, Rivesville’s 829 citizens are 98 percent white and that 1.68 percent, or 14 people, “are of two or more races.”

After Simpson was fired, the nearby town of Salem hired him as a police officer. While conducting his background check, Salem law enforcement officials could not get any information about Simpson from Rivesville officials, who refused, citing they feared Simpson was preparing to bring a lawsuit, the complaint alleges.

Rivesville subsequently hired Officer Nathan Lanham, who was working part-time for a few local police departments in the area (and who has recently gained notoriety for a violent traffic stop of a woman in nearby Monongah that went viral, prompting his resignation).

Lanham, who is white, was hired at a higher pay rate than Simpson (who earned $20 an hour), even though Lanham was a recent graduate of the West Virginia Police Academy, the lawsuit states. He received new safety equipment at the time of his hiring, which Simpson had requested but was denied. Lanham and another white police officer who had preceded Simpson in the job were given a work credit card with a credit line of $1,000, while Simpson’s credit line had been limited to $300.

Simpson’s complaint says Lanham contacted the Salem Police Department and made false accusations against him, including that Simpson had failed to turn in a safety light, work cellphone and cleaning supplies for his police car. Simpson says he had made a point of making sure that city officials observed him turning in the phone the day he was fired and had otherwise accounted for the other items with the city.

“Throughout his employment, Officer Simpson suffered systematic race discrimination and retaliation both perpetrated and ignored by officials of the Town of Rivesville,” Sean Cook, an employment law attorney, told Atlanta Black Star. “Indeed, the instant facts resemble a novel detailing race discrimination in the 1950s or 1960s in small-town America. Such discrimination was unacceptable then, and it remains unacceptable, as the deeply troubling events supporting Officer Simpson’s case occurred merely two years ago. The civil rights of Officer Simpson were violated, and we will aggressively pursue justice on his behalf.”

Simpson is asking the Marion County court to award back pay, front pay, legal costs, and damages for loss to his professional reputation and future earnings and for emotional, physical, and mental distress. He also demands a jury trial.

The Town of Rivesville’s answer to Simpson’s complaint is due to be filed on Aug. 28.

Jeffrey Cropp, the attorney representing Rivesville in this lawsuit, did not respond to an interview request by Atlanta Black Star and told the Times West Virginian that its lawyers do not respond to reporters on cases in which they are involved.