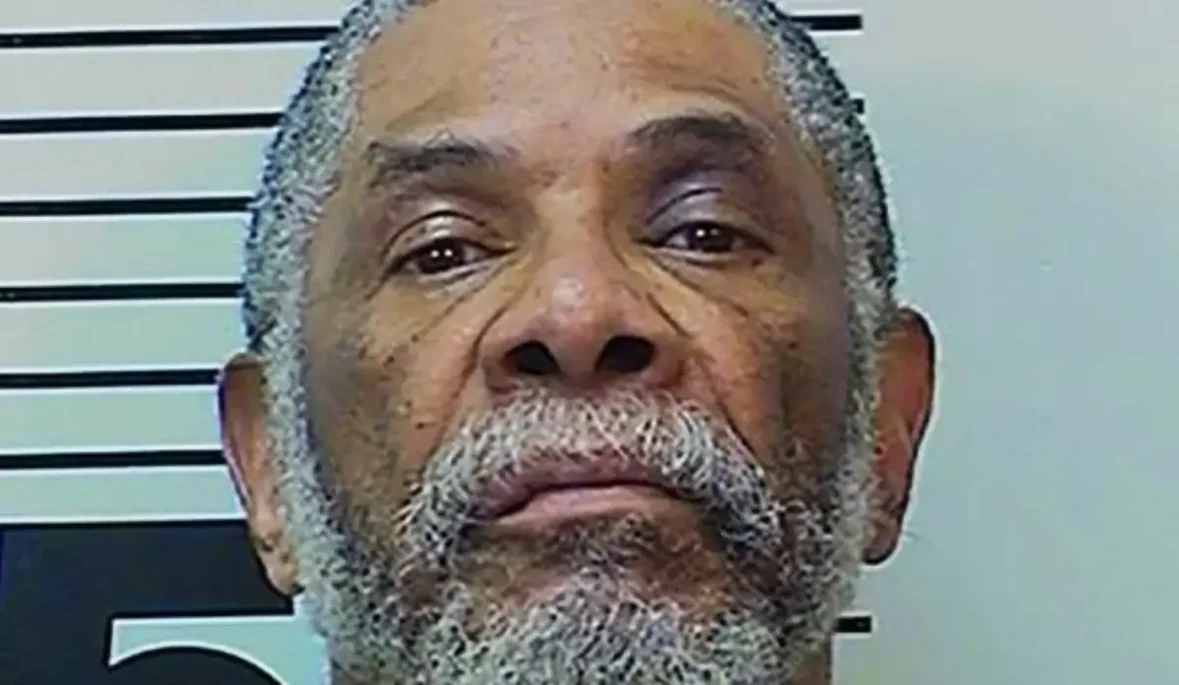

A Black man who’s been on California’s death row for 33 years for murder must either be released or retried due to prosecutorial misconduct in jury selection during his trial, according to an order issued by a federal judge last week.

Curtis Lee Ervin, 71, was convicted in 1991 in Alameda County for a 1986 murder-for-hire and sentenced to death. In subsequent appeals, his attorneys argued that prosecutors illegally excluded African-Americans from his jury panel, violating his constitutional rights.

The California Supreme Court denied his appeal in 2000, ruling that prosecutors had valid reasons to strike nine of 11 prospective Black jurors and that doing so was not a violation under Batson v. Kentucky, landmark case law which holds that using peremptory challenges to remove potential jurors based on race, sex or ethnicity violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

But a recent review of the case by California Attorney General Rob Bonta led him to concede that the court should have found Batson violations in Ervin’s case. At Bonta’s request, on Aug. 1, U.S. District Court Judge Vince Chhabria ordered the state to release Ervin from prison or to commence a retrial within 60 days.

“We hope they will do the right thing and not retry this case,” Pamala Sayasane, an attorney who has represented Ervin for 23 years, told Atlanta Black Star. “It’s been 38 years, and my client has always maintained his innocence, so we just hope they will do the right thing. You know, he’s not in good health. He just wants to live the rest of his life as a free man. It’s been a very long struggle for him.”

Ervin was found guilty of first-degree murder by a mostly white jury in 1986. Only one seated juror and one alternate juror were Black.

According to the 2000 appellate decision by the California Supreme Court, Ervin was hired by his co-defendant, Robert McDonald, to kill McDonald’s former wife, Carlene McDonald, for $2,500.

“The record shows…on November 7, 1986, defendant Ervin and codefendant Arestes Robinson kidnapped Carlene from her home” and drove her to a park, “where they stabbed her to death and left her body.”

Robinson told police he held Carlene McDonald down in her car while Ervin stabbed her five times. Police later recovered “Carlene’s watch, ring and automobile” in the possession of Ervin, who “admitted various incriminating aspects of the crime” to the investigating officer.

Ervin and McDonald were sentenced to death, and Robinson was given a life sentence. McDonald and Robinson both died in prison.

Sayasane has argued in legal briefs since then that prosecution witnesses lied and that other evidence was improperly introduced.

“There was a lot of misconduct in this case, not just in jury selection, but just in terms of how this entire trial was prosecuted by the DA at the time, James Anderson. So I hope Pamela Price will take a very good look at this case and see that the right thing to do is just to not retry a case that was full of tainted evidence and false evidence. … The right thing to do here is to release Mr. Ervin.”

Sayasane told CNN Ervin was “overjoyed and in disbelief” when he heard the news of the judge’s order last week. “He’s grateful to everyone who helped him. I’m in a daze, as is my client.”

The dramatic turnabout in Ervin’s case was prompted by Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price, whose staff recently discovered other death penalty cases where prosecutors deliberately excluded Black and Jewish prospective jurors. Price said that practice started in the 1980s and persisted through the 2000s.

Price said her prosecution team had uncovered boxes with notes revealing racial profiling of jurors by deputy district attorneys during the jury selection process and a clear bias against potential Jewish and Black jurors. She brought this to the attention of defense attorneys and the federal judge.

In April, Chhabria ordered Price to conduct a review of all of Alameda County’s 35 death penalty sentences with inmates still alive. Last month, three of those death row inmates convicted in Alameda County were resentenced.

Among them were Ernest Dykes, who was convicted of killing a 9-year-old boy in 1993. The judge found that prosecutors had excluded Black and Jewish people from the jury in his case.

“Must go” was written next to the name of a Black man; another had the word “Jewish” underlined on their questionnaire, CNN reported.

Dykes is expected to be released from prison next year with two years of probation, according to CBS/Bay City News, which noted that seven people associated with the Alameda DA’s office are under suspicion of misconduct, including current Assistant District Attorney Michael Nieto.

Anderson, the former county prosecutor, is now retired. He told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2021 when Ervin’s racial bias challenge was revived by the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, that race didn’t play a role in his questioning of prospective jurors in Ervin’s case.

“I don’t care if they were Black, or white, or whatever … if they weren’t able to give me a definite answer about how strongly they felt on the death penalty, they were gone,” Anderson said, according to KCRA.

Sayasane said Anderson’s racial bias was clear to her and to the Ninth Circuit federal appellate court Judge John B Owens, who wrote the opinion for the judicial panel, which ruled 3-0 to send Ervin’s case back to the trial court.

“He [Anderson] struck nine Black prospective jurors, and when the other side says, ‘Wait a minute, we think you violated Batson,’ meaning that you’re intentionally striking Black jurors, he has to give a reason,” said Sayasane. “And the court looked at that when they reversed and remanded this back to the trial court. They said that the reasons given by Anderson didn’t mesh, meaning that they didn’t believe his excuses.

“‘I struck the Black jurors because I didn’t think they could vote for death,’ [Anderson said]. Well, he didn’t have any problems with white jurors who said the same thing,” Sayasane continued. “Some expressed even stronger views against the death penalty. So, that was a problem the court had. It was inconsistent. And you can tell Anderson was just not being honest.”

The problematic death penalty cases brought to light by Price and her staff indicate a deeper, systemic racial bias among prosecutors to many in the legal and civil rights communities.

“This gross injustice is just further evidence of the racially biased application of the death penalty law not just in Alameda County but across California,” said Yoel Haile, director of the criminal justice program at the ACLU of Northern California, last month during a June rally in Oakland. “Public defenders and defense attorneys in Alameda County have been raising the alarm for decades about the unethical and downright illegal practices of this DA’s office. … The widespread nature of these practices indicates that they were either accepted or outright encouraged this level of prosecutorial misconduct in search of convictions at all costs.”

Price, who is facing a recall vote this November due to complaints about violent crime in the Oakland area, has not yet disclosed how she and Alameda County prosecutors will proceed with Ervin’s case. She has until Sept. 30 to file for a retrial or to negotiate a sentencing settlement with Ervin’s defense attorneys.

If neither happens, Ervin will go free.