As gun violence in Atlanta plagues Black youth, victims are becoming younger, and a growing chorus of affected families and community leaders seeking solutions say they have had enough.

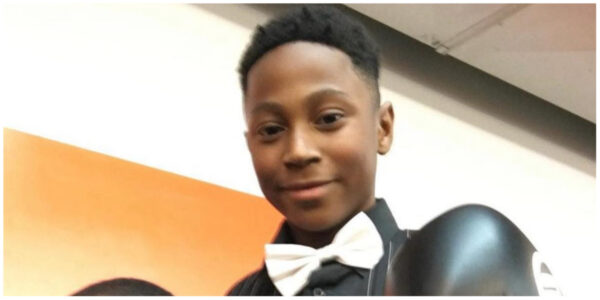

Cameron Jackson, 15, was a recent victim of Atlanta’s gun violence after visiting one of the city’s popular shopping plazas.

“Cameron was the love that brought our family together,” Tiffany Smith said of her son.

Cameron aspired to become an Olympic athlete and loved boxing. His life was cut short on Nov. 26 when other teenagers targeted him in a shooting. He was part of a group of youth kicked out of the city’s Atlantic Station shopping plaza during Thanksgiving weekend for “disorderly behavior.” Police say at least three teens riddled him with gunshots on the outskirts of the open-air mall.

Zyion Charles, 12, also died in the shooting.

Police since have arrested three teenagers for Cameron and Zyion’s murders.

While still grieving her son’s death, Smith is looking at his death as a symptom of a larger problem.

“This is not a chance to blame people. This is an ‘our’ problem; all of us are responsible,” Smith said.

Atlanta mayor Andre Dickens said on Nov. 27, “This is a village assignment. When 150 kids are outside unsupervised and three handguns recovered, there are a lot of factors at play, including parental supervision, easy access to guns, a cultural acceptance of violence and lack of conflict resolution skills.”

Smith echoes the mayor’s sentiments and is turning her attention to a community-based approach to addressing gun violence. Two months after her son’s death, she launched ‘Forever Cameron,’ designed to help mentor at-risk youth.

“Creating a village where we support each other; I’d say that’s where we’re falling short,” Smith said.

“There’s old wealthy Black Atlanta and then there’s new Negro Atlanta. There’s got to be a merging of amalgamation and sense of community and not individual success,” Jamal Bryant said.

Bryant is the pastor of New Birth Missionary Baptist Church. He says Atlanta’s Black community must come together regardless of social class. He also believes the city’s business and academic communities must provide opportunities for Black youth.

“We need to be steering financial institutions into helping young Black males into entrepreneurship and wealth creation,” he said.

In March 2022, the Atlanta Police Department made a plea asking the community to come together and address juvenile violence. “We could cite far too many incidents where children have been killed recently in avoidable shootings,” the post said.

In 2021, the Georgia Bureau of Investigations reported 23 people 16 and younger were arrested for murder, and 364 were arrested for aggravated assault. Among people aged 17 to 21, reportedly 122 were arrested for murder, and 892 were arrested for aggravated assault.

Nationally, homicide is a leading cause of death for children in the U.S., JAMA Pediatrics reported.

Black boys were killed more than any other group, and firearms were the most common weapon used. The rate of homicides in Black children increased by 16.6 percent from 2018 to 2020. Black boys 16 and 17 had a homicide rate 18 times higher than white boys of the same age.

The study says poverty, racial disparities, underfunded schools and few safe spaces contribute to youth violence.

Gerald Griggs is president of Atlanta’s NAACP Chapter and a practicing criminal defense attorney. He has been one of the leading voices amid the violence. He’s advocated a shift from a reactive response to a proactive response.

Griggs places part of the blame for Atlanta youths’ easy access to guns on statewide gun laws.

“We don’t need 12, 13, 14, 15-year-olds dying and nobody addressing the elephant in the room,” said Griggs.

In April 2022, Georgia governor Brian Kemp signed into law Senate Bill 319. It allows permitless carry of a concealed handgun in public.

Georgia Public Broadcasting reported, “In 2020, more than 280,000 permits were granted with around 5,300 denied because of a criminal history.”

Proponents of the bill, including Kemp, claim criminals are already stealing guns and disregarding existing gun laws.

Griggs was among the bill’s critics. He claims lax gun laws increase the chances of guns becoming stolen and falling into the wrong hands.

“Many times, the stolen guns end up in the hands of youth through improper gun storage and/or thefts of weapons,” Griggs said.

Leon Smith, executive director of Citizens for Juvenile Justice, shares Griggs’ sentiments. He goes further by outlining why at-risk youth gravitate toward guns in the first place.

“Black youth access and possess guns for the same reason many Americans do: because many do not feel safe,” Smith said.

Smith said communities and police must come together and address the safety concerns of Black youth. He also believes more emphasis should be placed on illegal gun trafficking.

“Georgia does not require a background check in private sales of firearms, so oftentimes permit applications are the first time a check is required,” GPB reported.

“When you have unfettered access to firearms and people who don’t know how to deescalate situations, you have a proliferation of gun-related deaths,” said Griggs.

Aside from gun access, Griggs also points to hip-hop culture. He says it promotes a violent lifestyle to Black youth.

“When I have artists that come sit in my chair across from me, they’re crying. They’re saying they don’t want to go to prison because they’re capping in their rap. We’ve got to stop the capping in the rap,” Griggs said, referring to rappers who falsely embellish their lifestyles in their lyrics.

Griggs said the community must step up and mentor the youth. He said they need guidance on how to resolve conflicts that arise over social media.

Social media led to a Dec. 17 shooting that left Justin Powell, 16, and Malik Grover, 14, dead.

“We’ve got to be honest with these young people. Show the real ramifications of the gun violence, the real ramifications of unresolved beefs that leak from social media and into reality,” Griggs said.

Psychologist Charmain Jackman says Black boys and teens are discovering their self-identity during adolescence.

During adolescence, youth will flock to spaces they feel supported and validated. The convergence of social media and hip-hop culture is often attractive to Black boys and teens.

“We have a lot of messages about what is cool in Black culture. Who is cool and what it looks like. We run into problems where we have these stereotypical ideas of what it means to be a Black man,” Jackman said.

Atlanta-based rapper Young Dro is taking a stand against youth violence. Young Dro, whose real name is Djuan Hart, said he’s released a new song called “Guns Down.” He is also planning a panel discussion to address youth violence on Jan. 26.

“When kids hear it, they misinterpret what we’re actually meaning by it,” Young Dro said.

Other contributing factors Jackman says play a role in Black youth violence include the lingering effects of the pandemic. She also blames a broken mental health system with few Black male therapists.

Jackman urges parents and caregivers to be more vigilant so they can pick up warning signs before tragedy strikes. Jackman says anxiety and depression are contributing factors affecting Black boys and teens. These mental health conditions may present differently in Black boys and teens than what we’re familiar with in other demographic groups.

“It may not look like a depressed kid. It may be more anger or irritability, a loss of a sense of self-worth, a shortened sense of future, like ‘Am I going to live very long?’ If we look at it, we may view it as they’re just behaving badly and not understanding the root causes of that behavior,” Jackman said.

Withdrawal, changes in friendships, drug abuse and changes in behavior at home or school are other signs something could be wrong with Black youth possibly experiencing anxiety or depression.

She encourages parents concerned their child is heading down a troubled path to listen to their child’s concerns and show unconditional love.

As for Smith, she applauds community members speaking out on the violence ripping apart Black families. Her newly launched Forever Cameron nonprofit organization is in its early stages. It will provide mentorship, after-school programs, scholarships and a boot camp for at-risk Black youth.

She hopes to capture her son’s loving spirit, with the organization bearing his name, and to bring the community together to curb the violence.

“If we don’t support our young people, then what future do we have?” Smith said.