A pair of brothers is suing the Michigan county that cost them 25 years behind bars for a murder they did not commit.

The wrongful conviction lawsuit accuses police of conspiracy and asks for $125 million to hold them accountable.

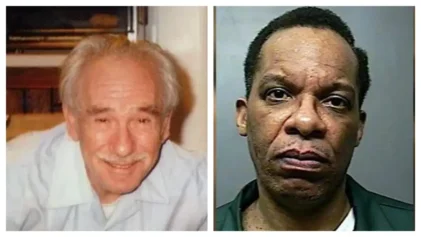

For brothers, Melvin DeJesus, 49, and George DeJesus, 45, they are left with many questions they hope their multi-million-dollar lawsuit will help answer. The most pertinent question they’ve wrestled with is why the lead investigator and polygrapher roped them into a murder they had nothing to do with. They hope their lawsuit prompts the accused to own up to the allegations outlined in their lawsuit.

“Why was this evidence suppressed? Why did they do everything they did to secure a conviction?” said George DeJesus.

The DeJesus brothers are suing Oakland County, Michigan, and specifically name the lead investigator, William Harvey, accusing him of promising one of the prime suspects in the case, Brandon Gohagen, a lighter sentence if he passed a polygraph test. The lawsuit also accuses polygrapher Chester Romatowski of fabricating the test results to help police secure a conviction.

“When they start cheating to win, the whole system suffers, and that’s what we have here, 50 years of wrongful conviction,” said Wolf Mueller, DeJesus brothers’ attorney.

As for the DeJesus brothers, they found themselves sandwiched in the middle of the crime, costing them a quarter century of their lives behind bars.

The incident that changed George and Melvin’s lives happened on July 11, 1995, when a woman who had been raped was found dead lying nude in the basement of her Pontiac, Michigan home. She had a pillowcase over her head and wires tying her neck, wrists, and ankles together. The woman, Margaret Midkiff, was the DeJesus brothers’ next-door neighbor.

Police were able to connect Gohagen to Midkiff through DNA evidence.

Western Michigan University Cooley School of Law reported, “Gohagen originally told police that the DeJesus brothers had nothing to do with the crime. Later, he confessed to sexually assaulting the victim but claimed that Melvin forced him to at gunpoint.” He also claimed, “Melvin and George then bound and beat the victim to death.”

The brothers say they knew Gohagen from high school and were friends at the time but did not know he raped their neighbor. They also say they did not know he made them suspects in the crime.

“Because they knew him and they were friends, and they lived next door to the murder victim, this became a simple jump over the dot you need to connect to get to a logical conclusion,” said Wolf Mueller, attorney for the DeJesus brothers, explaining the police logic tying the DeJesus brothers to the crime.

“When the investigators came and started asking questions after my neighbor was murdered, I didn’t have any knowledge of what happened. I was in disbelief of the whole situation,” George DeJesus said.

The brothers denied involvement in Midkiff’s murder and claimed they were at a house party when she was raped and killed.

“We had an alibi. There was no physical evidence,” Melvin DeJesus said.

According to the lawsuit, police interviewed witnesses at the time that corroborated the brothers’ whereabouts but failed to hand those notes over to the prosecutor. The lawsuit also alleges Harvey and Romatowski conspired to pin the murder on the DeJesus brothers in addition to Gohagen.

The polygraph helped lend credibility to Gohagen as the state’s principal witness. The polygraph test also helped tie the DeJesus brothers to Midkiff’s murder.

Michigan State University revealed details of a proffer agreement Gohagen arranged with prosecutors in 1997 ahead of the DeJesus’ trial.

“Gohagen had taken a polygraph test as part of his proffer agreement, and the Oakland County Prosecutor’s office was told Gohagen answered truthfully,” MSU said in its review of the case. “

To ensure a favorable polygraph test result, the DeJesus allege within their lawsuit, Romatowski prepared Gohagen for the test and told him how to answer the questions.

“Other than having sex with Margaret, did you cause any other injuries to her?” the lawsuit claims Romatowski asked Gohagen.

Other questions included, “Did you see Margaret with a pillowcase over her head? Did you hit and/or strike Margaret in the head?” For all the questions outlined, Gohagen was instructed to answer “no.”

MSU also said while CIU re-examined the evidence, “based on new guidelines, the polygraph was now seen as inconclusive.”

The suit further added the polygrapher failed to give his exam charts to the prosecutor and that he “fabricated test results.”

“She relies on the police, their integrity, and their results; certainly, the prosecutor is not a polygraph expert. She goes by what the police tells her. That’s the evidence she knows and presents,” Mueller said of Donna Pendergast, the prosecutor on the case.

During the trial in December 1997, George and Melvin presented their alibi defenses, claiming they were at a party the night of July 8, 1995. The prosecutor questioned their witnesses, but their inability to remember the exact date proved pivotal in the case.

The jury remained unconvinced by the DeJesus brothers’ witnesses because they could not remember the day of the week the party occurred during their testimony. On Dec. 30, 1997, George and Melvin were both convicted and sentenced to life without parole for first-degree murder, first-degree criminal sexual conduct, and felony firearm. The day of their convictions was the last time the brothers saw each other for 25 years as they were sent to different prisons.

Over the years in prison, the brothers say they always maintained their innocence.

“We always maintained our innocence. We helped as much as possible with the investigation when police came around, we talked to them, we tried everything in our power to help them,” Melvin DeJesus said.

While incarcerated, they fought to get their case appealed and re-examined.

“We went through 12 years of appeals. We filed appeal after appeal, we started in the trial court, and we were denied. We filed an appeal in the appellate court in Michigan and were denied. We were denied every step up,” George DeJesus said.

The brothers say they called multiple lawyers and organizations that could help their case get a second look. They eventually contacted the West Michigan University Cooley Innocence Project.

The Cooley Innocence Project then contacted Michigan’s Conviction Integrity Unit to help re-examine evidence in a review of the DeJesus brothers’ case.

The CIU reviewed witnesses and documents related to the DeJesus brothers’ case. “The CIU located witness statements made within weeks of the crime that corroborated the brothers’ alibis the night of the murder,” the CIU case analysis revealed.

The CIU also discovered additional details on Gohagen, the man who claimed George and Melvin forced him to rape Midkiff. Gohagen sexually assaulted and murdered another woman in 1994 and “acted alone” in that crime. In addition to the 1994 case, the CIU discovered 12 other women who were “emotionally, physically, and sexually abused by Gohagen.” He was later convicted of the 1994 sexual assault and murder in 2017.

“The CIU also interviewed a witness who said that Gohagen confessed to implicating the brothers in exchange for a deal. Pretrial and post-conviction DNA testing never identified the brothers’ DNA at the crime scene, and there was no other physical evidence linking the brothers to the crime,” WMU-Cooley School of Law reported.

After the CIU’s investigation, it moved to have George and Melvin’s convictions vacated and requested the dismissal of all charges.

“We spent year, after year, after year, and this stuff could have freed us; it’s frustrating,” said George DeJesus.

As the brothers’ convictions were overturned, Michigan Judge Martha D. Anderson apologized to them.

“I wish to apologize for the actions taken by your fellow citizens against you 25 years ago. Twenty-five years of your life have been taken from you that cannot be replaced. Hopefully, you will find some solace in the fact that you will be able to rejoin your family and start living a normal life outside the prison walls,” Anderson said.

Their lawsuit accuses Oakland County, Romatowski and Harvey of fabricating evidence, malicious prosecution, conspiracy, and Brady violations, which is withholding exculpatory evidence from the defense.

The lawsuit asks for $50 million in compensatory damages and $75 million in punitive damages. The brothers hope accountability comes in the form of a monetary settlement and answers to why they spent 25 years behind bars.

“We want to know answers. We want to know why this happened to us. We need this to stop and not continue,” Melvin DeJesus said.

Atlanta Black Star requested a comment from Oakland County’s Sheriff’s Office on the exoneration of the DeJesus brothers and questionable police work alleged within their lawsuit. The agency said in a brief statement, “it does not comment on pending litigation.”

The brothers were released from prison on March 22, 2022. Since their release, they have been adjusting to a normal life surrounded by family.

“It’s been a lot of adjusting, but it’s been great, I’ve been able to catch up with family, and I haven’t been around my brother for 25 years,” George DeJesus said.

Melvin has taken this time to build a bond with his daughter he met for the first time since being released from prison.

“Reuniting with family, especially my daughter,” Melvin DeJesus said. “We’ve been around different personalities and different things. When we came home, we had to change our mindsets to being free and speaking to loved ones,” he continued.

Gohagen is still serving 35 to 80 years in prison in the Muskegon Correctional Facility for first-degree criminal sexual conduct, felony murder and second-degree murder, the Michigan Department of Corrections records show.

In June 2022, the National Registry of Exonerations reported that each brother was awarded more than $1.2 million in state compensation for his wrongful conviction.

Exonerated prisoners in Michigan are eligible for up to a year of reentry housing and two years of other supportive services, including job placement, job training, transportation and more. The Michigan Department of Corrections pays for the services.