A Canadian police department has received backlash after creating a computerized image of a suspect they’ve never seen with DNA phenotyping.

DNA phenotyping predicts physical appearance or biochemical characteristics from forensic DNA samples found at a crime scene. The Edmonton Police Service in Alberta, Canada, released an image of a rape suspect on Oct. 4 using the technology. However, many voiced concerns that it could lead to the overpolicing and unnecessary profiling of Black men.

The victim in the 2019 sexual assault case could only describe the perpetrator as around 5 feet 4, having an accent, and wearing a black toque, pants, and sweater or hoodie. Edmonton Police Service said DNA analysis “indicates he is a Black male of entirely African ancestry with dark brown to black hair and dark brown eyes.

The police agency released the image, produced by Virginia-based Parabon Nanolabs, in a statement, and on its social media pages before removing it two days later and issuing an apology.

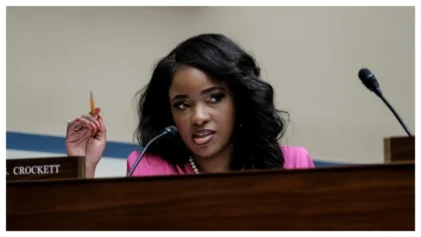

Callie Schroeder, the global privacy counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center, retweeted Edmonton Police’s tweet raising the alarm on the cause for concern.

“Even if it is a new piece of information, what are you going to do with this? Question every approximately 5’4″ Black man you see? …that is not a suggestion, absolutely do not do that,” Schroeder wrote.

“Broad dissemination of what is essentially a computer-generated guess can lead to mass surveillance of any Black man approximately 5’4″, both by their community and by law enforcement,” Schroeder later told Vice.com. “This pool of suspects is far too broad to justify increases in surveillance or suspicion that could apply to thousands of innocent people.”

Although the image was the first for Edmonton police, DNA phenotyping was introduced in criminal investigations in parts of the U.S. and Europe in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It has remained under the watchful eye of critics since then.

Race is not directly measured by DNA phenotyping but is determined by the visual nature of DNA composite profiles.

Racial profiling and racial disparities in policing have evolved from the slave patrols in the 18th century to Black people being stopped and frisked at significantly higher rates than white people in the 21st century.

Research also shows that Black Americans are more likely to be met with deadly force than white. While Pew Research Center data shows that more than 60 percent of the nation’s police officers are white, cross-racial identification could lead to errors in criminal cases, even with eyewitnesses.

While 15 percent of suspected Black murderers have white victims, 31 percent of Black suspects who were later exonerated and found innocent were convicted of killing white people, research shows.

Parabon examines crime-scene DNA to predict the suspect’s skin, eye and hair color and the presence of freckles. Edmonton Police said the company also predicted the suspect’s ancestry and face shape.

The final product showed the suspect at 25 with a Body Mass Index of 22. In its initial statement, the police agency pointed out that the image consists of “scientific approximations of appearance based on DNA, and are not likely to be exact replicas of appearance.”

“Environmental factors such as smoking, drinking, diet, and other non-environmental factors — e.g., facial hair, hairstyle, scars, etc. — cannot be predicted by DNA analysis and may cause further variation between the subject’s predicted and actual appearances,” the statement says.

Dr. Ellen Greytak, the director of bioinformatics and technical lead for the Snapshot division at Parabon, said the company is “providing facts, like a genetic witness, providing this information that the detectives can’t get otherwise.”

“It’s just the same as if the police had gotten a description from someone who, maybe you know, didn’t see them up close enough to see if they had tattoos or scars but described the person,” she said.

“What we find is that this can be extremely useful especially for narrowing down who it could be and eliminating people who really don’t match that prediction. In these cases, by definition, they always have DNA, and so we don’t have to worry about the wrong person being picked up because they would always just match the DNA.”

Critics have also argued that DNA phenotyping also gives way to personal privacy violations.

Greytak said Parabon uses publicly available data from studies the company has done and other forms of collection. A 2019 Buzzfeed investigation revealed that DNA comparison company GEDmatch allowed police to upload a DNA profile to investigate a crime.

Contra Costa County investigators were able to track down a serial rapist and killer, Joseph James DeAngelo, dubbed the Golden State Killer, in 2018 about three decades after he terrorized California. However, facing criticism, GEDmatch tightened its privacy policy.

Policies agencies in New York and California have faced lawsuits for collecting DNA from hundreds of thousands of detainees without their permission and storing it in a database. Texas public schools started distributing DNA kits to parents this week to secure the data to identify children in an emergency.

Parabon touts 60 of its success stories dating back to 2015 on its website. Parabon notes that many investigations are confidential and haven’t been made public.

Not all of the composites are potential suspects. The technology has been used for visual predictions of missing people and unidentified murder victims.

Enyinnah Okere, the chief operating officer for EPS sexual assault unit, said the DNA phenotyping snapshot of the 2019 rape suspect was the last resort for the victim who was left naked and unconscious in minus 27-degree weather on the side of a road. The suspect wore bulky winter clothes and a face mask making it difficult to identify him.

Okere said the goal was to seek justice for the woman, who is also Black, but admitted that he failed to properly weigh the risk.

“While the tension I felt over this was very real, I prioritized the investigation – which in this case involved the pursuit of justice for the victim, herself a member of a racialized community, over the potential harm to the Black community,” Okere wrote. “This was not an acceptable trade-off and I apologize for this.”