The University of Pennsylvania plans to rebury some of the nearly 900 skulls obtained by a racist professor who pushed a theory that Black people are inferior to the white race.

Samuel George Morton secured crania from nearly every continent during the 19th century for his collection that has been housed at Penn Museum since 1966. Morton used the boned heads of Black people to link brain size to intelligence among races. The university moved some of the skulls from Morton Cranial Collection to classrooms on display since 2014. After the civil unrest of summer 2020, the university issued a statement condemning the racist concept and now vows to bury at least 13 Black Philadelphians whose remains — many taken from graves — are in the exhibit.

“We reject scientific racism that was used to justify slavery and the unethical acquisition of the remains of enslaved people,” a page link to the Morton Cranial Collection now says.

“The Penn Museum and the University of Pennsylvania apologize for the unethical possession of human remains in the Morton Collection,” it continues. “It is time for these individuals to be returned to their ancestral communities, wherever possible, as a step toward atonement and repair.”

The Philadelphia-based physician and anatomy professor amassed 867 skulls from the 1830s through the 1840s. He separated them in racial categories: Ethiopian or African, Native American, Caucasian, Malay, and Mongolian. He compared each category by brain size and concluded that Caucasians had the biggest brains and Africans had the smallest.

However, in 1978, scientist Stephen Jay Gould found that “Morton was unconsciously underestimating brain size for the Africans.” He would lightly pack the seeds he used to measure in the African skulls and overpack the Caucasian skulls, Gould found.

Morton noted only one of the 13 Black Philadelphians in research. He made it a point to tell the story of John Voorhees, a “Mulatto porter,” who died in 1846 at 35 years old from tuberculosis. Voorhees allegedly confessed to killing someone to a nurse while on his deathbed.

Former UPenn anthropology doctoral student Paul Mitchell wrote a report in February 2021 about Morton’s racist work. Mitchell said he suspects Morton chose to highlight Voorhees as a way to shame and brand him as a criminal posthumously, and this was a common practice in the 19th century. It was also common then for the Ivy League to accept racist ideas in curricula.

“When we talk about scientific racism and these intellectual, pseudoscientific justifications for slavery, they’re not all coming from the South,” Mitchell said. “Some of the most important ones are actually coming from the North.”

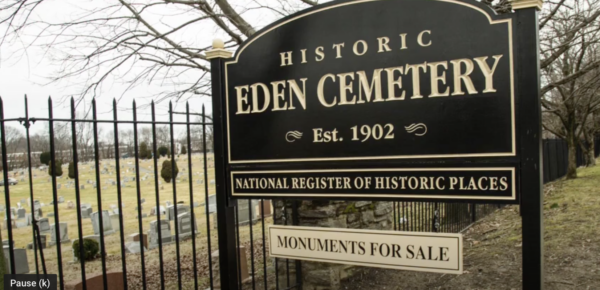

Penn Museum has asked the Philadelphia Orphans’ Court for permission to rebury the skulls in a historic Black cemetery outside Philadelphia called Eden Cemetery. If approved, the museum will hold an honorary ceremony in the fall.

“Our goal is to do the right thing and rebury these individuals after 170 or so years and do it as respectfully and as dignified as we can,” said Christopher Woods, the museum’s director.

The museum also plans to place a permanent marker of remembrance on campus after the ceremony and hold a community-led public forum “as part of steps towards restorative practices, atonement, and repair.”

In June 2021, Penn Museum created the Morton Cranial Collection Community Advisory Group, consisting of community, spiritual and city leaders and UPenn faculty and officials to develop the burial plan.

In August 2020, the museum formed a committee tasked with creating a repatriation plan for the remains. The advisory board evaluated the committee’s and Mitchell’s reports in its final plan, according to a museum press release.

The plan has received mixed reviews, however. Abdul-Aliy Muhammad, an activist and member of the community advisory group, is concerned that there may be other Black Philadelphians in the collection and raised questions about how the skulls were identified. He said the advisory board did not actually construct the plan. The museum director had already formed it and presented it to the board. Muhammad also argues that the university should not be in charge of the process because it is the root of the harm.

“I don’t think an institution that has financially, culturally and sociopolitically benefited from the violent removal of remains from the ground in the name of so-called science can be the same institution that holds the healing process,” Muhammad said

However, the Rev. Jesse Mapson, pastor at a West Philadelphia church and another advisory group member, said he supports the plan and believes it would create a bridge in the relationship with UPenn and Black Philapehia.

“Reconciliation does not mean to cover up your past. It means to look at it openly,” Mapson said. “Honestly, I think Penn has recognized its history in terms of what was done in another day and another time.”

The full collection is currently in storage in the museum’s Physical Anthropology Section. The university plans to coordinate the return of the 53 skulls of enslaved people from Cuba and hire a Black or brown bioanthropologist with experience in repatriation requests, who would also work at the museum.

“There is no’ one size fits all’ approach to handling repatriation and reburial in any circumstance,” Woods said. “Each case is unique and deserves its own consideration. This is incredibly sensitive work. And while we all desire to see the remains of these individuals reunited with their ancestral communities as quickly as possible, it is essential not to rush but to proceed with the utmost care and diligence.”