An incarcerated man is suing Kentucky prison officials for violating his legal right to religious expression by cutting his locs and retaliating against him when he complained, according to a lawsuit obtained by Atlanta Black Star.

The federal Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act and Kentucky’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act protect the religious freedom of people in prisons and jails. The laws also prohibit prison regulations that impose burdens on religious exercise unless the government “proves by clear and convincing evidence that it has a compelling governmental interest” and “used the least restrictive means to further that interest.”

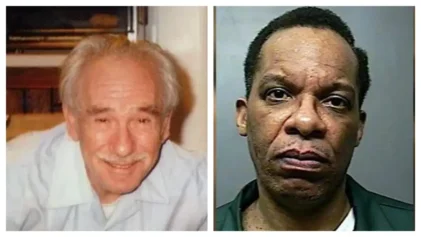

On Feb. 23, 2021, then-Warden of Northpoint Training Center Brad Adams wrote a memo requiring everyone in the Restrictive Housing Unit to have “searchable hair.” Those housed in the unit were no longer permitted to have “braids, corn rolls[sic], dreadlocks, etc., in their hair,” the memo said.

The memo said that anyone in the unit with braids, cornrows or locs had 30 minutes to remove them. “If the inmate refuses to remove them, then the hair will be cut using a cell entry team, with video. This is a use of force and must be approved using the normal process,” it said.

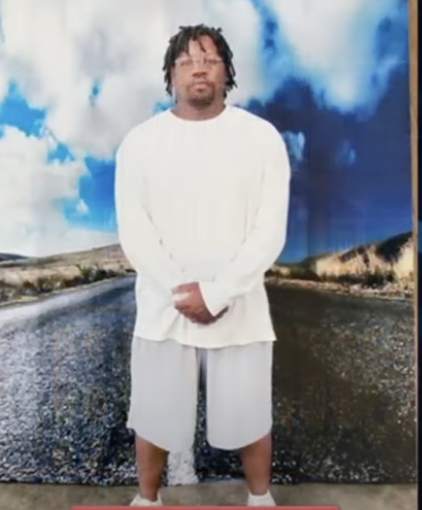

Carlos Thurman, a practicing Rastafarian, was among the prison population when the warden posted the memo on March 2, 2021. Rastafarianism follows the biblical vow of Samson that prohibits hair cutting, the lawsuit says. Thurman’s locs were two to three inches long at the time. He filed a grievance against the rule for himself and others, arguing that it was racially discriminatory and violated personal and religious liberty.

“If a white inmate with long hair down his back gets into a fight with a Black inmate with dreads, cornrows, or braids, the white inmate will be allowed to keep his hair,” Thurman wrote in his March 2021 complaint to the prison. But “the Black inmate will have to get his hair cut. Where is the fairness?”

Still, the prison forcibly cut Thurman’s hair and transferred him to another facility. Thurman believes that the transfer was in response to his opposition to the hair policy. After he filed the first grievance, Thurman filed two appeals. The grievance committee at one point recommended that the term “searchable” be defined for staff and the prison population, court documents show.

Then-Acting Warden Mendalyn Cochran in April said in her response to the grievance that staff needed to be able to search his hair for contraband. Thurman argued in the complaints that the policy violated his First and 14th Amendment rights and “failed to show that the cutting of braids, cornrows, and dreadlocks are the least-restrictive means.”

Thurman also filed a grievance on April 3, 2021, after he learned that Murray’s hair-care products, a brand made specifically for Black hair, were removed from the prison canteen. The lawsuit alleges Cochran requested that Thurman be transferred out of the facility on April 8, a day after she issued her decision on his initial grievance.

The lawsuit alleges Thurman was awakened at 1 a.m. on April 30, 2021, and told to pack his belongings. Thurman said that was the first time he knew of the transfer. About seven months earlier, he requested a transfer to a new facility after he was approached about helping launch a grievance process there since he was a grievance aide, but that transfer request reportedly was denied.

Before transporting him to a different facility, staff cut Thurman’s locs that he had been growing for three years over his objections and grievances. Thurman said he ultimately complied because he feared further retaliation.

At no time did prison staff search Thurman’s hair for contraband. Instead, they placed his short locs, which were as wide as No. 2 pencil, in a bag and gave it to him. The lawsuit alleges the prison did not use the least restrictive means to “satisfy the prison’s security interest,” and overstepped his religious protection as a result.

“While my hair was being cut, NTC staff were laughing with each other while staring at me. Even after because of how my hair looked with the dreads cut. This was humiliating to say the least,” Thurman wrote in a letter to Kentucky Department of Corrections Commissioner Cookie Crews.

After the transfer, Thurman kept filing complaints against the policy and the cutting of his hair. Kentucky prison officials since have changed the policy, they said. Thurman’s legal team said he filed the lawsuit to ensure no other inmate has to go through what he did. He named seven prison officials in the suit, including Crews and Adams.

Kaili Moss of the ACLU of Kentucky, one of Thurman’s attorneys, told Atlanta Black Star that even though the civil rights group did not sue for racial discrimination, it is “obvious” the policy was racially motivated.

“I believe that a policy that specifically names braids, cornrows, and locs, all culturally Black hairstyles is meant to target Black men, similar to how dress codes and grooming policies and workplaces and schools respectively, target Black employees and students,” Moss said. “There is definitely a real-world bias against natural hairstyles rooted in general ignorance about Black hair and also white supremacy. And so I think that bias exists in Mr. Thurman’s case, too.”

Kentucky Department of Corrections spokesperson Katherine Williams told USA Today the department’s current search policy “applies to all inmates regardless of race or gender” and that the department is still being reviewed. The prison system also uses full-body scanners to check for contraband.