Harvard University, America’s oldest college or university has recently admitted its role in the propagation of slavery, including setting up programs to engage descendants of those enslaved on the campus and work with other African-American people and institutions in academia. Now Massachusetts’ highest court has ruled the university can be pushed to do more to rectify its participation in the nation’s greatest sin, siding with a descendant of two enslaved persons forced to pose for pictures that since have been widely published.

On Thursday, June 23, the state’s Supreme Judicial Court vacated parts of a lower court’s 2021 ruling that blocked Tamara Lanier’s 2019 lawsuit to sue Harvard University for its use of photos she says feature her enslaved ancestors. It stated that Lanier and her family can plausibly make a case for “negligent and indeed reckless infliction of emotional distress” from Harvard has been imposed on her family. This part of the claim has been remanded to the high court, the Associated Press reported.

Further, the justices noted the Ivy League university failed to inform Lanier or the estate when it used one of the images of her relatives on resources for a campus conference in 2014, and a book cover in 2017, despite being aware of her relationship to the people within the images.

The ruling read in part, “In sum, despite its duty of care to her, Harvard cavalierly dismissed her ancestral claims and disregarded her requests, despite its own representations that it would keep her informed of further developments.”

Lanier’s attorneys, Ben Crump and Josh Koskoff, said, “We are gratified by the Massachusetts Supreme Court’s historic ruling in Tamara Lanier’s case against Harvard University for the horrible exploitation of her Black ancestors, as this ruling will give Ms. Lanier her day in court to advocate for the memory of Renty.”

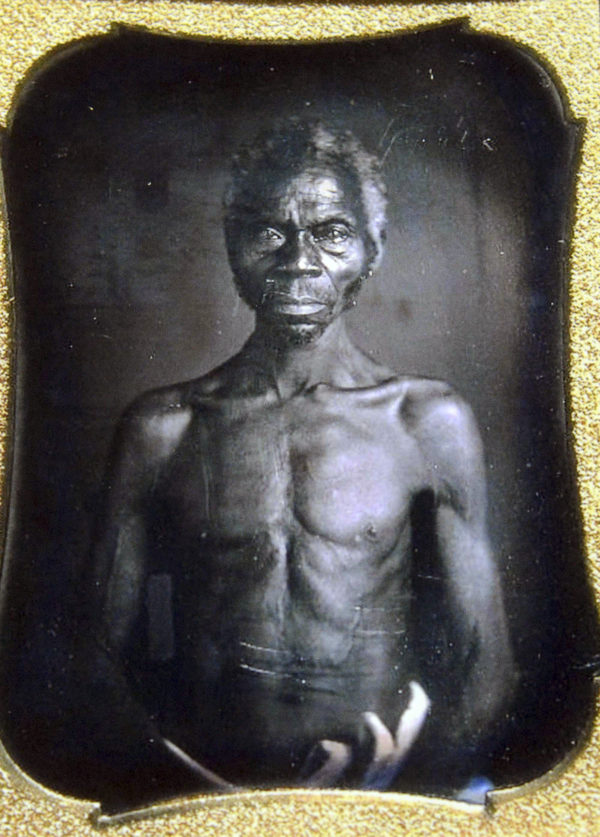

According to civil rights attorney Crump, Renty Taylor and his daughter, Lanier’s forebears, were forced by Harvard to pose for photographs “without consent, dignity, and compensation.”

A petition, set up by Lanier, described Taylor as “an extraordinary man who taught himself and other slaves to read and conducted secret Bible study meetings on the plantation where he was enslaved.”

“The photograph of Renty was taken in 1850 by a preeminent Harvard professor named Louis Agassiz who was trying to ‘prove’ that Black people were inherently inferior in order to justify their enslavement, subjugation, and exploitation,” the petition says. “Renty and his daughter, Delia, were forced to strip naked and pose for these dehumanizing photographs.”

Harvard continues to use these images, profiting off their license and historicity, “while denying its complicity in Agassiz’s terrible crimes.”

According to The Washington Post, Harvard had “lost” the images and rediscovered them in 1976 in its Peabody Museum collections in 1976, where they now are archived and kept.

Justice Scott Kafker included his opinion on the ruling, saying, “Harvard’s past complicity in the repugnant actions by which the daguerreotypes were produced informs its present responsibilities to the descendants of the individuals coerced into having their half-naked images captured in the daguerreotypes.”

Josh Koskoff, the co-counsel for Lanier and her family, said this was a “historic win” for the United States. It represents one of the first court rulings on the side of people who can trace their ancestors back to slavery.

While he applauded part of the court’s ruling, he did not agree with the second half, comparing it to “revenge porn” or sex-trafficking images.

The court did uphold the photos as belonging to the Agassiz and not Taylor or his daughter, despite them being featured in the images, ruling, “A descendant of someone whose likeness is reproduced in a daguerreotype would not, therefore, inherit any property right to that daguerreotype.”

“Harvard is not the rightful owner of these photos and should not profit from them,” Koskoff remarked in a statement. “As Tamara Lanier and her family have said for years, it is time for Harvard to let Renty and Delia come home.”

Rachael Dane, a spokesperson for Harvard University, says the school will review the decision, but stressed the original daguerreotypes remain in archival storage, and not on display for the public. She further stressed the images have not been licensed or lent to other museums in two decades, because of how fragile they are — not because they were sensitive to the family’s complaints.

“Harvard has and will continue to grapple with its historic connection to slavery and views this inquiry as part of its core academic mission,” she said. “Harvard also strives to be an ethical steward of the millions of historical objects from around the globe within its museum and library collections.”

Earlier this month, the Harvard school newspaper, The Crimson, leaked the April 19 draft report created by the University’s Steering Committee on Human Remains, stating that Harvard’s Peabody collection, where the Taylor images are stored, has over 7,000 more images of enslaved people (both African and First Nation). It further reveals the school, by owning these artifacts, ignored a 1990 federal law that required repatriation of the remains of a great many.

“Our collection of these particular human remains is a striking representation of structural and institutional racism and its long half-life,” the draft report’s introduction states.

Once the news was released by the Crimson, the school was “deeply frustrated,” believing it jeopardized the work they have been doing to heal the wounds between the community, the school and the descendants of the slaves.

Professor Evelynn M. Hammonds, the steering committee’s chair, remarked, “It is deeply frustrating that the Harvard Crimson chose to release an initial and incomplete draft report of the Committee on Human Remains.”

She wrote, “Releasing this draft is irresponsible reporting and robs the Committee of finalizing its report and associated actions and puts in jeopardy the thoughtful engagement of the Harvard community in its release. Further, it shares an outdated version with the Harvard community that does not reflect weeks of additional information and Committee work.”

In Spring 2022, Harvard announced a pledge to spend $100 million in an effort to atone for its active and passive participation in the institution of slavery.

Part of those plans is to research and identify descendants of enslaved people who worked on the campus. It also released a detailed report outlining in great detail many of the presidents and high-ranking administrators and alumni who profited off of the exploitation of free labor from people of color — including those with buildings named after them.