A former Illinois corrections officer faces life in prison for brutally assaulting a man in his custody and covering up his actions.

On April 25, a jury found Alex Banta, 30, guilty of conspiracy to deprive and deprivation of Larry Earvin’s civil rights, which led to inmate’s death. According to reports, 13 guards were involved in the Earvin’s fatal beating in a blind spot at the Western Illinois Correctional Center in Brown County, Illinois, in 2018. Three of them were charged in the incident.

The jury in the federal case could not agree on Banta’s co-defendant Lt. Todd Sheffler’s role in the killing. Banta was also found guilty of obstruction of an investigation, falsification of documents and misleading conduct. He faces a possible life sentence.

A third guard, Willie Hedden, pleaded guilty to two counts of civil rights violations. He was a government witness in the case.

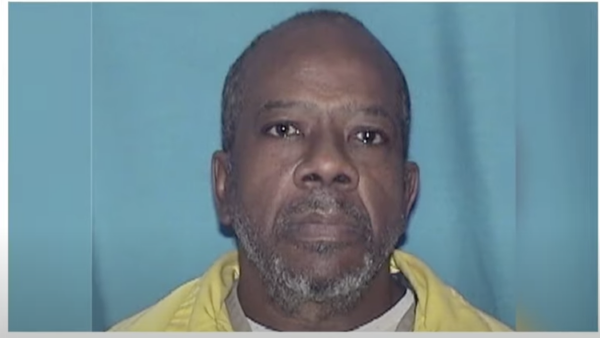

Earvin, 65, lived with schizophrenia and was homeless at the time of his arrest for petty theft in 2015, according to his family. He was months away from his release date on May 17, 2018, when a handcuffed Earvin was kicked, punched, stomped and jumped on in a section of the prison unit that had no cameras, according to reports.

Earvin died from blunt trauma to the chest and abdomen nearly six weeks later. His autopsy report says he had 15 rib fractures, more than two dozen abrasions, hemorrhages and lacerations. Prosecutors said doctors liken the injuries to those sustained in “a high-speed car crash.”

Earvin had to have surgery to remove part of his colon. He developed pneumonia and had a tracheostomy tube and a chest tube to drain fluids because of the chest trauma, reports show.

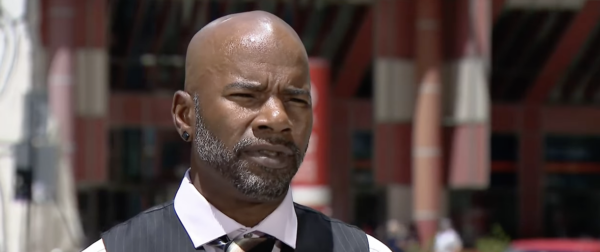

“It’s hard knowing how he died. That’s the tough part. And knowing that he was the type of person who wouldn’t hurt or harm anyone. And for him to die that way, it’s kind of tough,” Earvin’s son Larry Pippion said.

Pippion added to ABC7, “You don’t even treat animals like that, the way they did. To have him handcuffed, he couldn’t defend himself. To be kicked and beaten and punched.”

Defense attorneys argued that there is conflicting evidence about when the beating happened, who was involved, and contradictory testimony from witnesses, according to reports.

Stanley Wasser, Banta’s attorney, said the state was “trying to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.”

Prosecutors said a guard told Earvin to go back to his cell and lock up because he was not allowed in the yard, and he refused. Lt. Ben Burnett tried to handcuff Earvin from behind but failed.

Burnett then used pepper spray to get the inmate on the ground and handcuffed him. Burnett and other guards escorted Earvin to segregation, when the guards became frustrated because Earvin was “being difficult,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Eugene Miller said.

The Associated Press reports that Banta was with Earvin from the beginning and the end of the incident. Sheffler joined the escort along the way to the segregated unit where the assault happened. Sheffler and Banta never told investigators that they were in the segregated area.

The jury unanimously convicted Banta but was split 9-3 on Sheffler’s fate. However, jurors still believe Sheffler knew about the beating and tried to cover it up.

“Those who were on the fence were on the fence because they didn’t think the assault happened in [segregation],” juror Kevin Sullivan said.

The Western Illinois Correctional Center corridor, hidden from surveillance cameras, is notorious for beatings, reports show.

Roger Latimer told NPR that he was beaten by guards in the same blind spot before Earvin was killed. He asked medical staff to take pictures and complained to prison and local officials, but nothing was done.

Earvin and Latimer were not alone.

Another inmate was beaten to death in the same corridor a year before Earvin’s death. Pippion said family members of other inmates reached to him chronicling beatings in the excluded corridor for years.

Earvin’s family had filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the two guards and the state. A January hearing for the family’s demands for compensation, damages and justice did not end in a settlement, leading the way for the trial.

After his death, the prison buried Earvin in an unmarked grave, the family’s attorney Jon Erickson said.

“Even in death, this administration took away Mr. Earvin’s humanity, took away his family’s ability to mourn and bury him in a decent and human way,” Erickson said.