A white woman who raised $200,000 in the name of Philando Castile to pay off or supplement student lunch debt in the St. Paul school district, must pay back $120,000 to the state for misappropriating the funds. State prosecution states the fundraiser only gave a fraction of the money raised to the intended cause.

The New York Times reports that on Monday, March 28, the office of Minnesota’s attorney general, Keith Ellison, announced that Pamela Fergus, a former psychology professor at Metropolitan State University, has agreed to a settlement that will repay thousands of dollars collected during an online fundraiser titled “Philando Feeds the Children.”

The agreement, which did not require Fergus to admit guilt, was filed in Ramsey County District Court. Now, by court order, she is banned “from handling charitable funds” in the state.

Fergus launched the fundraiser in 2017, a year after Castile was killed by a police officer during a traffic stop. Before his untimely death, the Black man served as a nutrition supervisor at the J.J. Hill Montessori school and often paid school lunch fees for students in need.

The disgraced educator promised “every dollar” donated would go to the relief of the lunch debts of elementary school students. The state alleges this did not happen.

In June 2021, the Charities Division of the Minnesota Attorney General’s Office sued Fergus for “failing to properly spend all the money she raised in the name” the man kids affectionately called Mr. Phil.

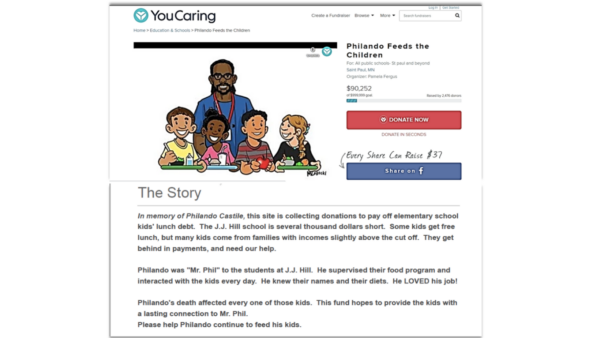

The lawsuit reveals Fergus originally set the target goal of the fundraiser at $5,000 on the crowdfunding platform YouCaring.org with a cause statement that read, “Please help Philando continue to feed his kids.” The page said the monies raised would go to the elementary school where Castile used to work.

Once a national spotlight was placed on the crowdfunding campaign money started to pour in. Fergus bumped up the target goal to $999,999 and raised $207,826 in cash for children who could not afford food during their break.

In October 2017, the woman was quoted saying, “We actually have enough money now to pay off all of the schools in the St. Paul public school district … So all of the grade schools, all of the middle schools, and all of the high schools. Plus, more. I mean, we’re still making money.”

“I don’t think there’s an end in sight,” the lawsuit says she said to a news outlet. “I want a million dollars in that account. That’s my goal. I want a million dollars.”

The money was pouring in, but it was deposited in her personal account and only $80,058.99 was donated to Saint Paul Public Schools. According to school officials, Fergus wrote three checks from the fundraiser to the district: (1) a check for $10,000 on Oct. 13, 2017; (2) a check for $35,035.99 on Feb. 27, 2018; and (3) a check for $35,000 on Aug. 13, 2018.

Fergus also proposed on the website that there would be an in-class service project for an undergraduate class she taught at the college connected to the effort to relieve school lunch debt for students.

Castile’s mother Valerie Castile suspected something was wrong with the charity drive and questioned how the money was being used. Her concerns prompted her to contact Ellison’s office and an investigation was launched.

In a statement to the attorney general’s office, the mother said about the settlement, “You should put that money where it’s supposed to go. These things are not for your personal gain. It’s not right.”

The attorney general said in a statement the monies received from the settlement will be distributed throughout the “Saint Paul Public Schools for the restricted purpose of paying off lunch debts of children in need — the purpose for which Minnesotans donated the funds in the first place.”

Minnesota laws around charitable giving and fundraising are clear.

“Those who raise money for a charitable purpose have important duties,” the attorney general’s office states. “They cannot mislead or deceive donors about how funds will be used, must use the money for the exact purpose that donors intended, and must have procedures in place to make sure the money is used properly. In addition, those who raise more than $25,000 or meet some other conditions must register and file specific paperwork with the Attorney General’s office.”

“This settlement helps to ensure that the money donors gave in Philando’s name will go back to where it was intended — to help Saint Paul kids who struggle to pay for school lunches,” Attorney General Ellison said.

He continued, “Philando Castile cared deeply about the children he served, and the children loved him back. Failing to use every dollar raised to help those children was an insult to Philando’s legacy and all who loved him.”

“This settlement helps right that wrong by continuing Philando’s commitment to serving students in need and ensures that the powerful impact he had during his life will continue to live as his legacy to the children and all of us.”

Ellison has paid particular attention to identifying people who commit fraud by initiating crowd fundraising campaigns, specifically during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the lawsuit, he cites a 2020 study on GoFundMe, a popular fundraising platform and states, “Between March 1 and August 31, 2020, GoFundMe donors gave over $625 million for relief efforts related to the COVID-19 pandemic — such as buying personal protective equipment for frontline workers or providing school supplies for students transitioning to remote learning.”

Ellison further reveals in just six months after George Floyd’s death, in another police-involved killing in the same state where an officer killed Castile, donors gave approximately $3 million in donations through online donations.

Under the settlement agreement, Fergus is mandated to pay Minnesota $400 each month from June to February 2024. On or before March 3, 2024, she has to cough up approximately $111,000 out of her retirement funds.

She will be immediately liable if she does not meet these payments and will be responsible for the total amount of her bill.