This is the second story in the three-part series titled “Below the Surface: The Fight to Protect African-American Cemeteries.” The series takes a look at the disparities and the ever-present systemic racism Black Americans face even in death.

One recent afternoon Edwina St. Rose and Bernadette Whitsett-Hammond walked an Atlanta Black Star reporter around Daughters of Zion Cemetery, a two-acre corner lot in Charlottesville, Virginia, filled with history.

The Daughters of Zion Cemetery was established by a charitable organization of African-American women in 1873. The cemetery is the final resting place of some of Charlottesville’s noted Black residents, including the Coles Family, who owned the largest African-American construction company in the city, and Benjamin E. Tonsler, who was a grade school principal and friend to Booker T. Washington. The last known burial came in 1995.

Both women created Preservers of the Daughters of Zion in 2016 to restore the cemetery after years of neglect.

“I grew up coming here every Memorial Day to place flowers on the graves of my relatives,” Whitsett-Hammond said while showing off her family plots.

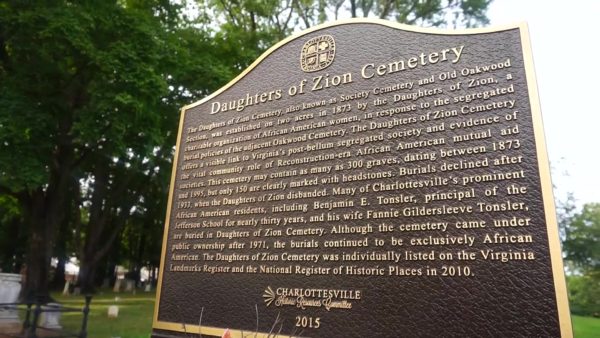

A plaque at the entrance of the cemetery welcomes guests and gives a brief description of its rich history.

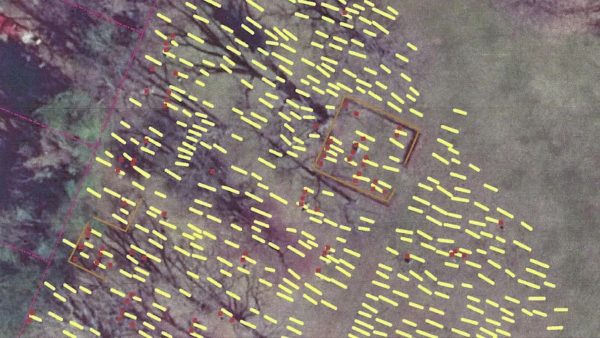

“It says the cemetery may contain as many as 300 graves, but recent ground-penetrating radar identified 641 visible burials,” St. Rose said.

“We always expected there were more than 300,” Whitsett-Hammond explained. “We had anticipated that people would be buried there because there’s so many indentations throughout the cemetery.”

The city of Charlottesville, which owns the cemetery, commissioned final ground-penetrating scan of the two-acre plot several years ago.

Mark Howard, senior geologist at NAEVA Geophysics, Inc., said the team worked on the site in three phases starting in 2016 and ending in 2019.

“Even if we could only see a meter into the ground, that might be enough to locate graves, because if we can image the grave shafts will suffice to identify the location of the burial,” Howard said.

Technology like this radar only works in certain conditions. The soil has to be just right to get a clean image.

Charlottesville is one of three places in Virginia that has the right soil. Howard explained that they also had to consider the age of the burials and what sort of condition they might be in.

“In a modern cemetery it’s quite easy,” Howard said. “People are now buried in coffins and go into a vault. The radar can see that very easily. But if you’re talking about someone that was buried in the early 1800s or late 1700s there may not really be anything left there to imagine. If they were buried in a casket, it would’ve been just a wood casket. More than likely that would be long gone. Many people were buried in shrouds so I think decomposition would be pretty rapid with that.”

Before the more positive shift initiated by the Preservers, the space was under-tended. Even accounting for racial resource inequality, legislation tended not to support these types of sites. Now even though technology has put a spotlight on the buried past, Whitsett-Hammond says we may never know the names of those who were discovered.

“The memorial to the unknown is dedicated to the individuals who we will never know their names,” Whitsett-Hammond said. “I think many of the descendants would like to know where their ancestors are buried. Unfortunately, here with so few markers I don’t know that it’s ever going to be possible to identify exactly who is buried where.”

The unmarked gravesites are reminiscent of systematic efforts to diminish African-American people in the past. Currently, a pointed stone memorial sits just behind the plaque at the Cemeteries entrance that is dedicated to all the nameless bodies laid to rest there.

The Preservers of the Daughters of Zion continue to search for families of those buried on the grounds. Statewide registration didn’t begin until 1912, so those buried before that date won’t have a birth certificate and won’t be able to be identified unless there is an obituary or a family member comes forward.