Martin Montravious Jones’ life is in limbo.

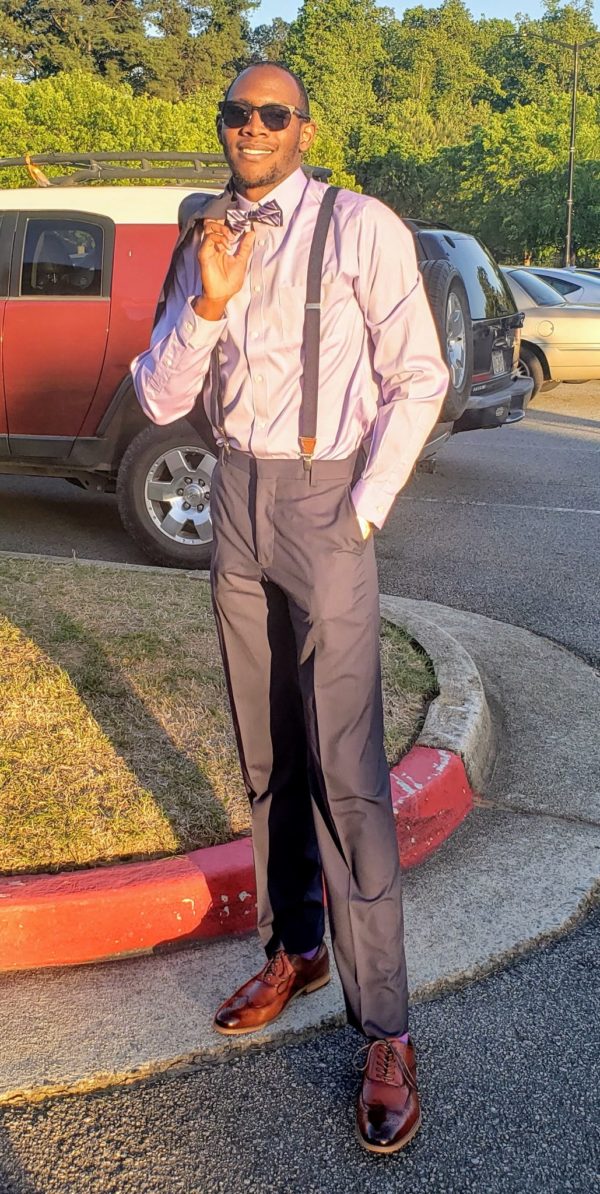

The 24-year-old Albany, Georgia, man graduated from Kennesaw State University in suburban Atlanta in May with dreams of becoming a civilian engineer with a government titan like NASA, SpaceX or the Warner Robins Air Force Base just outside of Macon.

While those dreams are on hold for now, in part because of COVID-19, Jones now worries that another looming threat may jeopardize his future.

In March 2019, he was wrongfully arrested because of a snafu by police in his hometown. Jones shared the same first and last name with a man accused of damaging his ex-girlfriend’s car and house during a 2018 domestic dispute.

Instead of the actual suspect, Albany police mistakenly issued a warrant for Jones and he was arrested on his college campus hundreds of miles away. He spent a day and a half in a Cobb County, Georgia jail before authorities realized they’d arrested the wrong man.

It was an unfortunate digital case of mistaken identity. The charges against Jones were eventually dropped. But he worries that the arrest will still show up on his background as he strives to start his career.

Jones has filed a federal lawsuit against the two Albany police officers responsible for writing the warrant that led to his wrongful arrest and is seeking more than $1 million in damages. But a clean name is the priceless thing Jones is trying to recover as he works to clear his record.

“I don’t know what truly is still on my record right about now,” Jones told Atlanta Black Star. “I mean … it could still say domestic violence charges or criminal trespassing charges. If you run my name through a background search, it could pull up I was arrested. Being that a lot of engineering jobs for bigger companies, you have to have security clearance to work with the government. When they do their security clearance check and go on an in-depth background search, pretty much take my background apart piece by piece, what will they find?”

The arrest

Martin Jones had never been in trouble with the law when he embarked on his senior year at Kennesaw State, where he majored in mechanical engineering.

He was 22 at the time and had never even so much as been pulled over for a traffic stop.

That all changed the night of March 18, 2019. Jones was driving to a party, but forgot to turn on his headlights. A Kennesaw State University police officer stopped him near his dorm, gave him a warning for the minor traffic offense and let him go.

Little did Jones or the officer know at the time, Jones had a outstanding warrant for his arrest in Albany, Georgia, his hometown more than 200 miles away. After running his information, campus police called Jones and asked him to come to their headquarters. He showed up around 3 a.m. and officers informed him he had an outstanding warrant. Jones told them it had to be a mistake because he was at school at the time, not in Albany. But officers said he had to settle the matter with authorities in Dougherty County.

“It was terrible. I was in shock,” he said. “I honestly didn’t know how to react other than just to comply, because, you know, I didn’t want to make the situation worse being that Cobb County isn’t the best county for a Black male to get arrested in.”

Jones was taken into custody, detained in a holding cell for hours and then booked into the Cobb County Adult Detention Center. He was charged with two counts of second-degree criminal damage to property, felony counts punishable by up to five years in prison apiece.

Jail guards told Jones they were simply detaining him for the warrant and would contact Dougherty County authorities, who would come pick him up if they wanted to extradite him back to Albany to face the charges.

The warrant stemmed from a Dec. 16, 2018, argument in the small Georgia town. A woman named Ashante Jackson told officers her ex-boyfriend used a wooden board to knock holes into the walls, windows and floors of her home, according to a police report. She also said he threw a concrete brick through the front windshield and rear windows of her 2002 Mercury Cougar.

Jones called his mother before he was placed in a cell and told her he was locked up. LaTasha Jones was getting ready to head out of town for work at the time. Martin Jones told her there’s no way he could’ve done what he was accused of because he wasn’t back home in Albany at the time. He assured her he hadn’t made any enemies there either who would file a false police report against him. She quickly jumped into action to free her son.

“She pretty much had to balance getting ready to leave to get on the road and try to figure out how to clear my name and pretty much prove that I’m the wrong person that they have,” he said. “Her and my grandmother were working together to get that taken care of. Luckily, they got it done within a 48-hour time span, before I could get picked up to be brought down to Dougherty County.”

LaTasha Jones and her mother went to the Dougherty County Jail and the Albany Police Department, showing officers Martin’s birth certificate, address and other information to prove he wasn’t the man they were looking for. They even produced his online time logs from a part-time job, which showed he was working in Atlanta when the alleged incident occurred.

Eventually they got a supervising officer to listen and pull the case records, according to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Dougherty County sheriff Kevin Sproul acknowledged that he was the wrong Martin Jones, and a Dougherty County magistrate judge dismissed both charges, according to court records provided by his attorney.

Martin Jones wasn’t released from jail until 1:30 the following afternoon, more than 34 hours after turning himself in.

The mistake and lawsuit

An arrest report from the Albany Police Department listed two names as suspects the police sought for destroying Jackson’s property. One was Martin Deontrez Jones, a 29-year-old Black man. The other was Martin Montavious Jones, who had never met the woman.

But Albany detective Tangela Henry, a detective for the Albany Police Department, swore under oath that Martin Montavious Jones was the man who committed the crimes. And a warrant for his arrest was issued in Dougherty County on Dec. 21, 2018, five days after the domestic dispute, according to court records.

Dexter Hawkins was the patrol officer who responded to the call. He wrote the original report, which listed Martin Montavious Jones as one of the two possible suspects, the federal lawsuit alleges.

The only reason his name even registered was because he applied for a concealed carry firearms permit in Albany shortly after his 21st birthday in 2017. When he did, the Dougherty County Sheriff’s Office added his name to a countywide database that law enforcement uses to track suspects, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported.

But former Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal in 2014 signed a sweeping gun rights bill into law that prohibited multi-jurisdictional databases from being compiled for gun-license holders. Gun rights attorney John Monroe, vice president of GeorgiaCarry.org, told the AJC that Dougherty County may have violated that law. A Dougherty County Sheriff’s Office official denied the database is illegal, telling the newspaper it’s only shared between agencies in the county.

William Godfrey, Jones’ Albany attorney, filed a civil rights lawsuit against Henry and Hawkins in U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Georgia.

Godfrey filed the original complaint against Detective Tangela Henry in the Superior Court of Dougherty County on Dec. 17, 2019. U.S. District Judge Leslie Abrams Gardner moved the case to federal court on Jan. 24. Gardner added Hawkins as a defendant in the case Nov. 4, upon motions from Godfrey.

Godfrey claims in the lawsuit that Albany police officers were “wantonly indifferent” to the fact that Martin Montavious Jones was not the man who actually committed the alleged crimes.

The civil complaint alleges unlawful search and seizure, false imprisonment, malicious, intentional and deliberate indifference by Henry and Hawkins and charges that the officers violated of Jones’ Fourth Amendment and due process civil rights.

“Anybody who sees the humanity in another human being knows that this never should have happened,” Godfrey said. “I mean, it was egregious; it was not right. Something went terribly wrong here.

“But from the legal standpoint, the unfortunate part about many of these cases is that over over the years, the case law shows that judges’ decisions regarding these cases has really been in favor of police forces,” he added.

Hawkins has retained Fred Lee, an Albany defense lawyer, to defend him. Lee did not respond to emails.

Meanwhile, Henry is being represented by Atlanta attorneys Sun S. Choy and Jacob Daly.

Daly declined to comment on Hawkins’ behalf this week. But he and Choy answered the claims in Jones’ lawsuit earlier this year, denying the claims that Henry acted maliciously, wantonly and without any evidence for probable cause when she swore to the arrest warrant. The attorneys, in their response, also argued that Henry was acting in her official capacity as a detective, so she has qualified immunity from the state and federal claims against her.

It wasn’t clear if Martin Deontrez Jones was ever arrested for the charges stemming from the 2018 incident. Albany Police Department did not immediately respond to questions from Atlanta Black Star about the case.

Godfrey said he’s been working with the department for months to negotiate a resolution to the case. Once the lawsuit is resolved, Jones can begin working to get the arrest restricted and possibly even sealed from his record in the state of Georgia.

“But the reality of it is if somebody wants to delve into his background, especially government employees, my position is chances are they’ll be able to see it,” Godfrey said. “We just hope that it won’t be a hindrance to him receiving gainful employment.”