An ex-prosecutor’s online memoir is turning heads in La La Land’s legal community.

For the past six weeks, a former L.A. County deputy district attorney has authored a series of real life stories detailing his 12-year career at the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office. He’s releasing the stories on Medium, an open publishing platform, under the pen name Spooky Brown, Esq.

The tales are a diary of disillusionment detailing the power struggle the former prosecutor endured trying to fight the good fight in a powerful assembly-line system of incarceration. He shares four specific stories rife with corruption, callousness, coercion and flat-out lies that he witnessed from police investigators and fellow prosecutors involved in the cases he handled.

“Most of the time, my supervisors have been white, and the people charged have been Black and Brown,” Spooky Brown wrote. “While some of those decisions have been right, too many of them have been wrong — dead wrong.”

The Atlanta Black Star has confirmed Spooky Brown’s true identity and verified he’s been a licensed L.A. County attorney since 2007. We are not identifying him to protect him from retaliation.

The Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office is the largest local prosecutorial office in the nation, with a brigade of 1,000 attorneys and 300 investigators pushing close to 200,000 cases through the courts each year. The area they serve is the nation’s most populous county, with 10.2 million residents.

Spooky Brown dissects that system in his series of stories. He takes a no-holds-barred approach in the anecdotes, diving headlong into them with headlines like “When Police & Prosecutors Are Partners in Crime” and “When Innocence is Inconvenient.” Last month, Spooky penned an open letter to outgoing L.A. County District Attorney Jackie Lacey, urging her to treat her Black female employees better.

That won’t be necessary much longer. Lacey was voted out of office eight days after he posted the letter.

L.A. County has long been notorious as a haven of corruption in the police ranks. It still has one of the highest rates of police killing citizens nationwide.

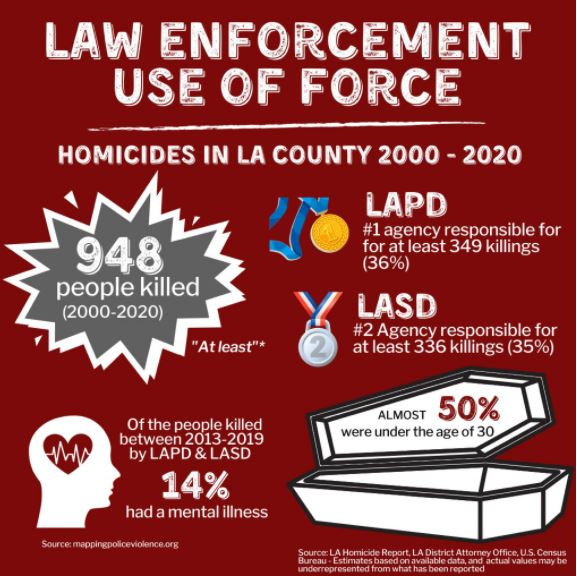

The Youth Justice Coalition, a Los Angeles activist group, estimates at least 948 people have been killed by law enforcement in L.A. County since 2000.

Black citizens made up 9 percent of the county’s population between 2010 and 2014, but accounted for 24 percent of the deaths from police shootings during that span, the Guardian reported. L.A. County district attorneys are responsible for prosecuting officer violence. But no charges were filed in the more than 1,500 police shootings from 2000 through 2018, according to the news site.

Lacey became the county’s first Black district attorney when she assumed office in 2012. But her refusal to crack down on the officer shootings, even under intense pressure, led to her demise.

Lacey was unseated in the Nov. 3 election by former San Francisco district attorney George Gascón. Angelinos opted for his progressive campaign over Lacey’s “tough on crime” approach in the wake of the George Floyd killing, according to The Guardian.

For Brown, Floyd’s death was the tipping point that inspired both his writings and his decision to resign from the DA’s office.

Derek Chauvin, the ex-Minneapolis police officer shown kneeling on Floyd’s neck for eight minutes, 49 seconds, was charged with second-degree unintentional murder and second-degree manslaughter for the now infamous May 25 encounter that sparked weeks of unrest and global cries for police reform over the summer.

Spooky Brown gave prosecutors the benefit of the doubt when he heard the news they filed the reduced murder charge against Chauvin.

“But then I made the mistake of watching the whole video and I was like, no, this is actual murder,” he told Atlanta Black Star. “Stone cold murder.”

“It changed me entirely,” he went on. “It changed my whole viewpoint of the world as far as law enforcement and prosecutions, because it made me see just how ugly the system can be. And how little Black lives do matter.”

Spooky Brown planned to write an essay at that point but got sick. He was also traumatized by the visual of Floyd’s killing. That delayed his creative process, but continued news of police violence reignited the fire.

“I remember a bunch more murders of Black people started happening, and the decisions of district attorneys were in question,” he said. “So I decided to restructure it in a way to let people know what DAs can go through on a daily basis. So they can have a pinpoint to see what kinds of things go into making decisions to file a charge on someone. And sometimes how very little it has to do with justice.”

Spooky Brown starts his series with an unabashed disclaimer, proclaiming the stories are “based on shit that actually happened.” The first installment, titled “Why I Don’t Trust Prosecutors,” is a four-part story that delves deeply into his first felony jury trial. A 21-year-old Black man named “Byron” was charged with resisting arrest and owning a weapon illegally. Police alleged Byron fought an officer during a traffic stop and when officers searched his home after the arrest, they found a gun hidden underneath the couch where he slept. Byron, a felon, was not allowed to legally own a weapon and faced up to seven years behind bars.

But certain details in the officers’ stories didn’t sound right to Spooky Brown, he wrote. Faced with the prospect that they were lying about what happened, he brought his concerns to his supervisor in the DA’s office. The supervisor ordered him to proceed with the trial, telling him it wasn’t his job to decide who was telling the truth.

“That’s the job of the jury.”

The young prosecutor’s suspicions proved correct, however. The morning of Byron’s trial, his public defender handed Spooky Brown a photo showing the couch in question sat squarely on the floor. That debunked the police narrative that an officer reached into the eight-inch space between the couch and floor to find the alleged gun and bullets in a cardboard shoebox.

The photo proved to Spooky Brown that Byron had been framed. But when he broke the news with his supervisor, instead of dismissing the case, he asked if Byron would accept a misdemeanor plea. After Spooky Brown pressed him, the supervisor relented but only agreed to dismiss the charges without prejudice, meaning Byron could be tried on them later.

But Spooky Brown ignored that order, he wrote, and dismissed the case entirely.

Spooky Brown began posting the personal stories Oct. 9 and periodically added more entries over the course of the month.

His latest was an Oct. 30 memo to Jackie Lacey titled “12 Years a Prosecutor, No More.” It’s addressed directly to the lame-duck top prosecutor and reads like a resignation letter, outlining Spooky Brown’s loss of faith in her as well as the crisis of conscience with his profession.

“Under your leadership,” he wrote, “it’s been a huge struggle for me to do the right thing without repercussion. It shouldn’t be this hard. Expending so much energy fighting for justice, while also fighting discrimination and continuous retaliation from within has left me tired, terrified, and disappointed.”

“This office has made it a point to make employees feel powerless when they speak out,” the excerpt continued. “I must admit, there’ve been times in which I’ve felt absolutely powerless and inept. However, by coming out and telling these stories, I’ve realized that everyone has a voice, and everyone has power. I hope to use my voice and power to encourage others to come out and tell their own stories.”

Spooky Brown said he continues to write and share more of his tales. He described Lacey as an example of an old-school, “business as usual” brand of criminal justice. Gascón, her successor, is part of a wave of progressive prosecution that he said gives him hope for the future of law enforcement. He listed Baltimore State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby, Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner and Kim Foxx, State’s Attorney of Cook County in Illinois, as other leading members of the wave.

“I think the mindset is changing in the sense that people now know what we do and how much power prosecutors have,” he said. “I think it’s about a greater accountability, a willingness to see criminal prosecution on a holistic level, and the willingness to be more independent of law enforcement.”