Shawn Parcells, a Kansas man who rose to short-lived prominence after he helped perform an autopsy on Michael Brown in 2014, has for years been accused of being a fake physician.

An indictment filed against him in federal court Wednesday, Nov. 18, added more credence to those suspicions. Prosecutors for the U.S. Attorney’s Office charged Parcells with 10 counts of wire fraud, alleging he was paid more than $1.1 million to perform hundreds of private autopsies, many of which he is accusing of never doing.

Each of the felony counts is punishable by up to 20 years in prison and $250,000 in fines.

The indictments added to Parcells’ growing list of legal woes. A district judge in Shawnee County, Kansas, last year banned the 41-year-old man and his companies from performing any more autopsies or conducting forensic pathology, the Kansas City Star reported.

Meanwhile, the Kansas Department of Health and Environment seized biological samples from Parcells’ offices, and he’s being sued by the Kansas Attorney General’s Office for violating the state’s Consumer Protection Act.

A forensic pathologist is a specialist who examines the bodies of the dead to determine the manner and cause of death. According to the eight-page indictment filed Wednesday, a pathologist must be a licensed physician certified by the American Board of Pathology.

Despite having no formal training, Parcells worked as an assistant pathologist for the Jackson County, Missouri, Medical Examiner’s Office from 1996 to 2003, the indictment alleged.

He went on to incorporate his own company, National Autopsy Services, in Topeka, Kansas, in 2016. His company’s website offered private autopsies, forensic pathology and tissue recovery services. The site also claimed the company’s pathologists were certified by the American Board of Pathology.

He was indicted for 10 wire transfers paid to his company between July 8, 2016, and Jan. 21, 2019.

National Autopsy Services usually charged clients a $3,000 up-front fee for the autopsies, which generally take 90 to 180 days. Federal prosecutors allege 375 clients paid Parcells’ company between May 2016 and May 2019, amounting to $1,125,575.15, but he failed to complete the majority of the services for which he was hired.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office is seeking a judgment to forfeit those proceeds or Parcells’ property if he’s convicted.

The indictment alleges no licensed pathologists worked for National Autopsy Services and Parcells faked his credentials to appear as though he was a qualified doctor. Prosecutors said he had no training or authority to submit autopsy reports, and he often kept his clients from filing complaints by telling them the cases were delayed because he needed more information. The indictment went to to charge that National Autopsy Services’ website misrepresented the company as a large corporation with offices internationally, when in reality Parcells operated just one morgue.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, in a 2013 investigative analysis, was one of the first to dispute Parcells’ credentials. The newspaper said he testified at murder trials and taught at universities under the auspices that he was an expert in forensic medicine. But there were concerns even back then that he was unlicensed and may have forged doctors’ signatures on autopsy reports.

CNN took aim at Parcells’ background after he became somewhat of a darling of cable news networks in 2014 after he helped perform a private autopsy of Michael Brown.

Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old Black teen, was shot and killed Aug. 9, 2014, during an encounter with Darren Wilson, a white Ferguson, Missouri, police officer that began as a jaywalking stop.

Wilson claimed Brown attacked him in his police vehicle, punched him several times and reached for his service weapon, forcing him to fire the gun twice. Brown and Dorian Johnson, a friend walking with him, both took off running at that point. Johnson hid behind a parked car. The officer said when he got out of his vehicle to pursue, Brown turned and bull-rushed him with his hand in his waistband. Wilson said he fired multiple gunshots and paused, but Brown continued to charge so he fired several more shots until the teen collapsed and died.

Johnson and several witnesses disputed Wilson’s version of events. Johnson told a grand jury the officer grabbed Brown by the neck during the confrontation near Wilson’s SUV and an intense “tug of war” ensued. He said he never saw his friend grab for Wilson’s gun, and Brown’s hands never went down toward his waist. Johnson claimed the officer opened fire as Brown was running away then let off several more shots after the teen turned around with his hands up and was surrendering.

Investigators recovered 10 spent shell casings at the scene. Brown was shot at least six times, but none of the bullet wounds were in his back, according to the St. Louis County Medical Examiner’s Office.

The shooting sparked months of unrest in the St. Louis suburb, with “Hands up, don’t shoot” becoming a rallying cry for protestors. It also triggered an FBI investigation and became a bedrock case of the Black Lives Matter movement.

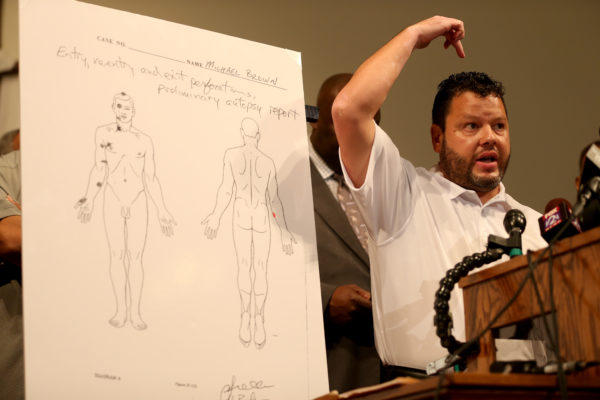

Brown’s family members asked for a private autopsy and hired Dr. Michael Baden, a highly touted forensic pathologist who once served as chief medical examiner of New York City, which also found no bullet wounds in Brown’s back.

“In my capacity as the forensic examiner for the New York State Police, I would say, ‘You’re not supposed to shoot so many times,’” Baden said at the time, according to The New York Times. “Right now there is too little information to forensically reconstruct the shooting.”

Parcells assisted in Baden’s autopsy and helped present its findings during a nationally televised news conference in August 2014. Baden called him instrumental in the evaluation, the Washington Post reported.

But CNN’s November 2014 investigation questioned if he was a fraud, suggesting he lied on his LinkedIn profile about being an adjunct professor at a Topeka, Kansas, university and claimed he was not licensed or certified. Parcells told the network he learned how to perform autopsies through “on-the-job training.”

A 2012 ProPublica study found a “pervasive lack of national standards” for death investigations. It highlighted the relative ease it took for a journalist with no medical training to be certified in forensics by passing an exam through online courses.