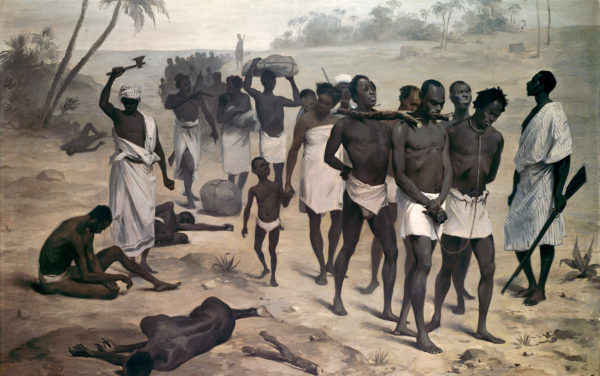

A groundbreaking study of the genetics of Black Americans highlighted lesser known aspects of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

The study, Genetic Consequences of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in the Americas, was spearheaded by consumer genetics company 23andMe and compiled genetic results from more than 50,000 volunteers, including 30,000 people of African descent, reported The New York Times. It was published in the American Journal of Human Genetics on Wednesday.

The research team compared the DNA data to records from vessels that transported millions of Africans across the Atlantic Ocean from 1515 to 1865.

“We wanted to compare our genetic results to those actual shipping manifest to see how they agreed and how they disagreed,” geneticist and study co-author Steven Micheletti told AFP. “And in some cases, we see that they disagree, quite strikingly.”

Micheletti said the team “couldn’t believe the amount of Nigerian ancestry in the U.S.”

The overrepresentation of genes from the region that is present-day Nigeria is attributed to “intercolonial trade that occurred primarily between 1619 and 1807.” Africans arrived in the British Caribbean and were later traded to the United States “presumably to maintain the slave economy as transatlantic slave-trading was increasingly prohibited.”

Genetic data from Senegal and The Gambia, identified as the Senegambia region in study, was underrepresented. This discrepancy was attributed, in part, to disease.

“Because Senegambians were commonly rice cultivators in Africa, they were often transported to rice plantations in the U.S.,” Micheletti explained, per BBC.

“These plantations were often rampant with malaria and had high mortality rates, which may have led to the reduced genetic representation of Senegambia in African-Americans today.”

An estimated 12.5 million Africans traveled the slave trade route and about two million did not survive the journey. Most of them, more than 60 percent, were men, but the data showed an overrepresentation of African female contributions to the modern gene pool. In the United States, African women contributed 1.5 more times than their male counterparts. In northern South America and the Latin Caribbean, the numbers were 17 and 13 times more, respectively. European men were also overrepresented compared against European women. In the United States, white male contributions to the gene pool of those of African descent are three times higher than those of white women. The number jumps to 25 times more in the British Caribbean.

The researchers believe these figures stemmed from higher mortality rates for male Africans in bondage as well as “the rape of enslaved African women by slave owners and other sexual exploitation.” In the United States, there was a “practice of coercing enslaved people to having children as a means of maintaining an enslaved workforce nearing the abolition of the transatlantic trade.”

The higher numbers of female representation in Latin America point to “branqueamento,” a policy that pushed African women to mate with Europeans “with the intention to dilute African ancestry through reproduction.”

Micheletti acknowledged the limitations of the study but he hopes it will spark new conversations about the legacy of slavery, according to NBC News.

“We don’t want these historical details to get swept under the rug,” Micheletti said. “We really want them to be discussed today and adding the genetic confirmation on to those details could be a powerful tool.