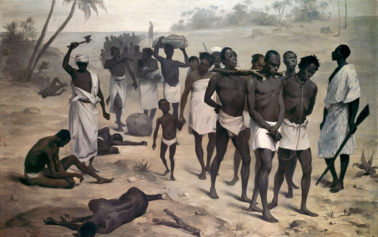

Three skeletons found by scientists in a mass grave in 1992 in Mexico City chronicle the horrific life journey of some of the first Africans who were transported to Latin America and enslaved some 500 years ago.

The bones display evidence of fractures, gunshot wounds, and the men’s introduction of infectious diseases during their enslavement in central Mexico. The study, published April 30 in the scientific journal Current Biology, paints a picture of the lives of many Africans during the early Spanish colonization and how their presence may have shaped disease dynamics in the New World, the study authors said in their joint statement.

“Using a cross-disciplinary approach, we unravel the life history of three otherwise voiceless individuals who belonged to one of the most oppressed groups in the history of the Americas,” senior author Johannes Krause, an archaeogeneticist and professor at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

The remains of the three individuals were found at the site of the ancient San José de los Naturales Royal Hospital in Mexico City, a hospital founded in the early 1500s to serve the indigenous community, which had been decimated by the time King Charles I of Spain authorized the importation of Africans to Spanish colonies as slaves in 1518.

The new analysis of the remains contributes to the study of African migration to Mexico during the 16th and 17th centuries, and points to why almost all Mexicans carry a small amount of African ancestry.

“Having Africans in central Mexico so early during the colonial period tells us a lot about the dynamics of that time,” said author Rodrigo Barquera, a graduate student at Germany’s Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. “And since they were found in this mass burial site, these individuals likely died in one of the first epidemic events in Mexico City.”

The bones revealed a life of hard toil and injuries, and once researchers extracted genetic and isotope data from the individuals’ teeth they got a better idea of how long they had lived in their homeland and which African regions they were taken from.

“Their genetics suggest they were born in Africa, where they spent all of their youth,” Barquera said. “Our evidence points to either a Southern or Western African origin before being transported to the Americas.”

One of the skeletal remains had remnants of gunshot wounds from copper bullets, while another had a series of skull and leg fractures. But, according to Barquera, the abuse did not end their lives.

“Within our osteobiographies we can tell they survived the maltreatment that they received,” the author said. “Their story is one of difficulty but also strength, because although they suffered a lot, they persevered and were resistant to the changes forced upon them.”

The remains also document the earliest signs in Latin America of hepatitis B and another contagious skin disease that is similar to syphilis.

“We found that one individual was infected with hepatitis B virus, while another was infected with the bacterium that causes yaws — a disease similar to syphilis,” co-author Denise Kühnert, a mathematician working on the phylogeny of disease, said. “Our phylogenetic analyses suggest that both individuals contracted their infections before they were likely forcibly brought to Mexico.”

The revelation has been extremely significant in the research as it suggests the impact of yaws, a chronic bacterial infection that affects the skin, bone, and cartilage, which was very common among Mexicans during that time. Kühnert found the research “plausible that yaws was not only brought into the Americas through the transatlantic slave trade but may subsequently have had a considerable impact on the disease dynamics in Latin America.”

However, one thing about their discovery was certain; it brought answers to a few deep-rooted questions regarding Mexican culture.

“We want to get insights into how pathogens emerged and spread during the colonial period in the New Spain, but we also want to continue to explore the life stories of the Africans brought here and other parts of the Americas,” Banquera said of further research. “That way they can take a more visible place in Latin American history.”