A recent expose found several American textbooks were teaching Black history incorrectly and downplaying the effects of oppression.

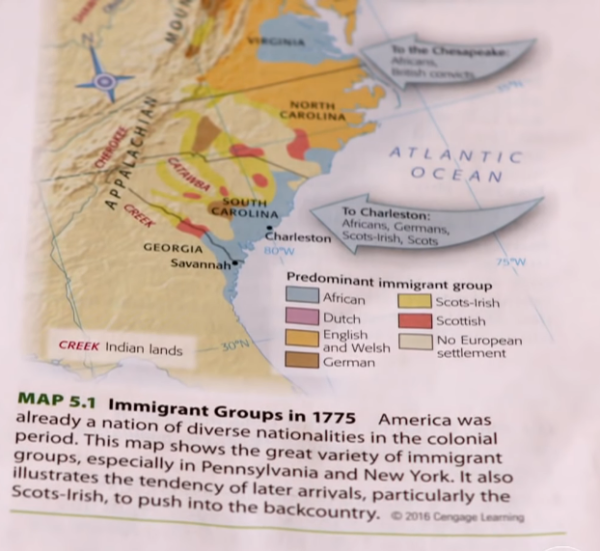

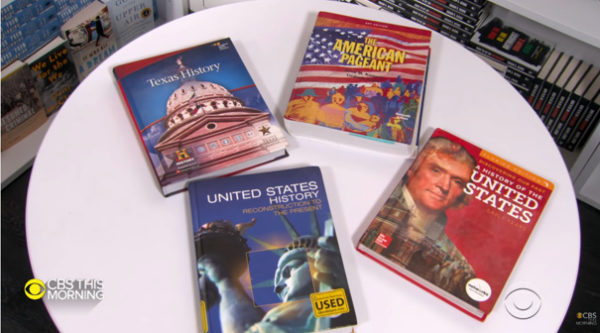

CBS News presented four textbooks to Dr. Ibram X. Kendi, author of the book, “How to Be an Antiracist,” who analyzed the texts for discrepancies. A map in “The American Pageant” used “immigrants” to describe enslaved Africans who arrived in the United States in 1775. They were listed beside German, Scottish and Dutch immigrants who entered the country voluntarily.

“To refer to them (Africans) again as immigrants insinuates that they chose to come,” said Kendi. “The African people who were almost totally … forced to come and certainly did not want to come to the United States in chains.” Two editions of the book, one published in 2016 and the other in 2019, have the map.

Kendi also took umbrage with the use of the term mulatto in the book, which is used to teach advanced placement history classes. The sentence in question also referred to the enslaved mothers of biracial children as the slave owners’ mistresses.

“The term mulatto, in many ways, is a racial slur, is a racist slur against biracial people,” he said. “The root of that word is mule, and so it was imagined in the decades leading up to the Civil War that biracial people were essentially like mules.”

Dr. Naomi Reed, an instructor at Southwestern University, pointed out the book’s portrayals of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

“Martin Luther King Jr. is sort of always colorblind, peaceful resistance, versus Malcom X is always violent, militaristic and radical. And so it almost sends a message that this is the right way, Martin Luther King Jr., is sort of the right way … that’s not the full picture of either one of them,” Reed told CBS. “The American Pageant” is used to teach over 5 million students a year, according to Cengage, the book’s publisher.

“Texas History,” a book geared toward middle-school students, explained slavery by stating, “some U.S. settlers brought slaves to Texas to help work the fields and do chores.” Kendi highlighted the use of the word “chore” and argued it minimized the brutality of slavery.

“Students, young people, have a very clean sense of what a chore is. That is something they have to do but they don’t like it. And I don’t think we should describe slave labor as chores,” Kendi explained. “For many of these people, this wasn’t a chore that they did on the side after they finished their homework. This was something that they literally had to do all day long or else.”

The omission or change of details have real consequences, according to a 2018 report from the Southern Poverty Law Center. SPLC surveyed 1,000 high-school seniors and determined the teens struggled with basic Black history. Only 8 percent named slavery as the primary cause of the Civil War and 68 percent did not know the Constitution had to be amended to free enslaved people. SPLC also interviewed over 1,700 teachers and the majority of them (58 percent) didn’t think the materials they used to teach slavery are adequate.

Kendi believes these textbooks are why many adults know little about Black history.

“Reviewing these texts closely, now I can see why so many students get to college and they’re like, ‘why didn’t we learn this in high school?’ Because it isn’t in these texts,” said Kendi. “When we instruct our children, we should be instructing them in truth.”