Black and Hispanic people bear the brunt of breathing the most polluted air despite not emitting the majority of it, a recent study found.

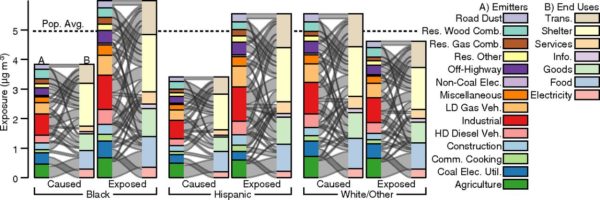

Findings published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in March revealed that Black communities have a “pollution burden” of 56 percent excess exposure of what they consume, while that of Hispanics is 63 percent relative to what they consume. Meanwhile, the study stated that non-Hispanic whites have a “pollution advantage” where they are exposed to 17 percent less air pollution exposure than their consumption causes.

Using analysis from Extended InMAP Economic Input–Output model and measuring fine particulate matter (PM2.5) air pollution, researchers analyzed end-use emissions, such as exhaust emissions from driving a car, construction and agriculture. They also reviewed those emitted from economic activities that support the end use, like emissions from the production of gasoline that fuels a car, food and electricity.

Particulate matter pollution can result in health issues affecting the lungs and heart, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The problems include decreased lung function, aggravated asthma, irregular heartbeat and nonfatal heart attacks.

Black people were found to be the most exposed of whites and those the study categorized as “other” to every emitter group, as shown in the accompanying graphic. Hispanics had the same result except for particulate matter that came from agriculture, coal electric utilities and residential wood consumption.

“Previous analyses have found that when considering only differences in locations of residence, exposure disparities by race are much larger than disparities by income,” the study, led by the University of Minnesota engineering professor Jason Hill stated. “Our results suggest that income, to the extent that it correlates with consumption, is an important factor in determining how much pollution a person causes, even if it may be statistically less important as a determinant of exposure. We also find that differences in racial-ethnic groups’ contribution to exposure are driven more by differences in their overall amount of consumption (magnitude effect) than by differences in the types of goods and services they consume (composition effect).”

Speaking to NPR, the paper’s first author Christopher Tessum made it clear this doesn’t mean white people should not be able to use their money for the consumption of goods and services, the ones of which they consume more of that result in air pollution compared to Black and Hispanic communities.

“We’re not saying that we should take away white people’s money, or that people shouldn’t be able to spend money,” the University of Washington postdoctoral researcher said.

Despite the findings and questions raised about how to address the disparity, however, more research needs to be done.