A set of data uncovered by University of California-Berkeley professor reveals southern white women played a heavier role in the enslavement of Africans than previously thought.

Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, an associate professor of history at the university, combed through data from the 1850 and 1860 census and revealed that white women made up around 40% of slaveowners.

The findings helped Jones-Rogers compile her book, “They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South.”

On her department page, Jones-Rogers describes the February 2019 release as “a regional study that draws upon formerly enslaved people’s testimony to dramatically reshape current understandings of white women’s economic relationships to slavery.”

In the book, Jones-Rogers explained that white women’s involvement in slavery comes from family, as their slave-owning parents “typically gave their daughters more enslaved people than land.”

“What this means is that their very identities as white southern women are tied to the actual or the possible ownership of other people,” she said according to History.com.

Her book also notes that owning enslaved Africans served as white women’s primary source of wealth. Plus, owning a large number of enslaved people reportedly made women better marriage material.

Once wed, white women were said to have fought and frequently won the right to continue to have ownership over their enslaved Africans, not handing over ownership to their husbands.

“For them, slavery was their freedom,” Jones-Rogers states in her book.

After Martha Washington married President George Washington in Virginia in 1759, George is said to have possibly owned around 18 people. But his wife, one of the richest women in the state, owned 84 and dramatically increased the local slave population.

Arguing that white women are trained to be engaged in the slavery industry at a young age, Jones-Rogers stated, “their exposure to the slave market is not something that begins in adulthood—it begins in their homes when they’re little girls, sometimes infants, when they’re given enslaved people as gifts.”

Jones-Rogers demonstrates that in her book by including interviews with formerly enslaved people conducted in the 1930s through the New Deal agency, Works Progress Administration. One formerly enslaved woman said children would ruthlessly beat enslaved people.

“It didn’t matter whether the child was large or small. They always beat you ’til the blood ran down,” she said.

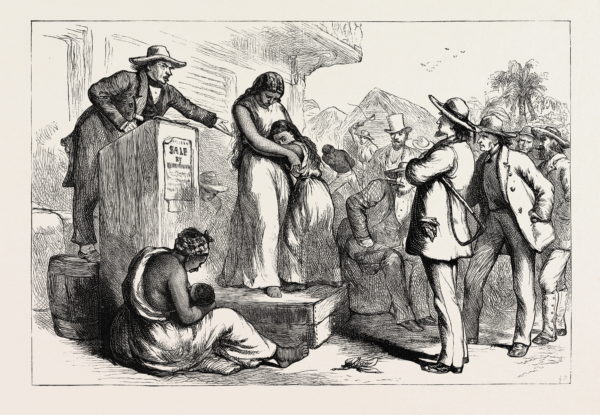

Once they came of age, white women also reportedly got involved in the slave market. Aside from beating slaves once they owned them, white women bought, sold and sought out their return. The notion flips the previous belief of scholars that white women abstained from engaging in such activity, as it was deemed improper.

As the women got pregnant and had their own families, they’d reportedly orchestrate sexual assaults between enslaved people so that enslaved Black women could be available to nurse white women’s children. This in addition to tearing enslaved women’s babies away from them so they could nurse white women’s children and avoid becoming, as Jones-Rogers stated one white woman slaveowner said, “a slave” to her children. Advertisements for “wet nurses” were plastered throughout newspapers, reportedly creating a massive market for enslaved Black women who recently delivered children.

“There were instances in which formerly enslaved people did, in fact, say that their mistresses either sanctioned acts of sexual violence against them that were perpetrated at the hands of white men; or that they orchestrated instances of sexual violence between two enslaved people that they owned, in hopes of producing children from those acts of sexual violence,” Jones-Rogers said.

White women were also said to have gone through great lengths to maintain ownership of their slaves as the Civil War waged on. History.com reports that one woman, Martha Gibbs forced enslaved Africans to Texas and threatened them with a gun to continue working for her through 1866, the year after slavery was officially abolished.

Even after the institution was outlawed, southern white women reportedly doled out work contracts that exploited Black people to work under slave-like conditions. Some described it as a benign industry — as Margaret Mitchell did in “Gone With the Wind.” That same idea has carried out through to textbooks discussing enslavement today. As recently as April 2018, it was exposed that students in Texas had been using a textbook that stated not all enslaved Africans were unhappy.

Still, Jones-Rogers argues in her book that white women’s “ideological and sentimental connections” to slavery weren’t the only thing that made them defend the practics. She remarked that women who were around during enslavement would have done the same.