New York Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration has taken steps to foreclose on over 400 homes in Black and Latino communities under a controversial policy allowing the city to take away properties, along with years’ worth of equity, from homeowners.

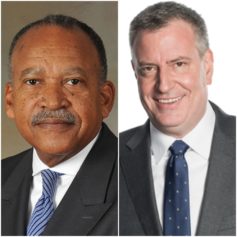

Mayor Bill de Blasio announced plans earlier this year to expand New York’s controversial third-party transfer program. (Photo by Sean Rayford/Getty Images)

The efforts were uncovered by records from the city Department of Housing Preservation and Development, the New York Daily News reported.

City data shows that communities in Brooklyn, the South Bronx and upper Manhattan have been most affected by the policy, commonly known as the third-party transfer program. The city has launched transfers proceedings under the policy on approximately 69 buildings across the Brooklyn communities of Fort Greene, Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant since De Blasio’s second year on City Council in 2015. Of those, seven properties have been transferred to interim owner and local nonprofit Neighborhood Restore.

Meanwhile, the city of New York also initiated third-party proceedings on an estimated 107 homes and foreclosed on 20 in local Council districts that includes Williamsburg, Bushwick, Brownsville and East New York, also in Brooklyn. Such was the case for three South Bronx districts, where 83 third- party proceedings have been launched since 2015, city data shows.

Eighteen of those properties are now under new ownership.

Citywide, the city has foreclosed 62 properties via the program in just the last four years. The program, which began in the 1990s under the administration of former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani as an alternative to the tax lien auctions that hit property owners who fall too far in arrears on property taxes or city water and sewer fees, gives the city more control over what happens to properties and their tenants than it would have for properties that fall into the hands of private bidders who snap up such buildings at auction.

Rising property values in neighborhoods that are becoming gentrified would increase taxes on properties in such communities, which often leaves many Black and Latino homeowners struggling to pay those higher tax bills and at risk of losing their homes.

De Blasio, who entered the race for president last week, announced in January his plans to expand the laws governing the contentious program, according to The Real Deal. Under his plan, seizure powers would be expanded in a new program to include “the worst buildings that have failed to correct violations and pay the debt they owe the City within a reasonable timeframe,” city officials said.

Not everyone is a fan of the program, however. Critics of the third-party transfers, particularly homeowners and lawyer-advocates, say the city has done a less-than-swell job of notifying property owners who are at risk of losing their investments.

“A lot of these homeowners had no idea these properties were being taken out from under them,” Scott Kohanowski of the City Bar Justice Center‘s Homeowner Stability Project told the New York Daily News. “And the city takes all that equity. That’s the most appalling part.”

Others, including City Councilman Robert Cornegy, argued that the program has already “proven deeply problematic for black and brown homeowners” in the city’s outer boroughs.

Several local politicians, including new Attorney General Letitia James Brooklyn borough president Eric Adams, have also criticized the program and called for it to be put under more scrutiny.

Serge Joseph, an attorney for residents of a foreclosed property in the Bronx, said their co-op board didn’t receive any notice before the building was handed to a new owner.

“[They] thought their arrears were being taken care of,” said Joseph. “They entered into an agreement plan with the Department of Finance. Then out of the blue, they were informed the co-op no longer owned the building and that the deed was transferred to Neighborhood Restore.”

As reported by the Daily News, “The current debt threshold for the city to initiate third-party transfer is at least $1,000 in city arrears for at least one year, or $1,000 for at least three years” via the city’s Housing Development Fund Corporation program. However, the city has its eye on properties with large amounts of debt — $900,000 to be exact.

City officials insist property owners and tenants are notified via mailed notices, fliers, robocalls, and even forums when their homes are being looked at for possible transfer. However, residents say it’s often too little, too late.

“[The city] told people there’d be no more shareholding, but they didn’t explain anything,” said Cecilia Jones, 74, who bought 250 shares for her unit in 1996. “They didn’t say why.”

Jones’ Dean Street apartment has since been taken over by Neighborhood Restore and the Bridge Street Development Corp.

“This whole group is just taking away people’s housing,” she told the newspaper. “That’s their purpose.”