WASHINGTON (AP) — Deeply troubled by a Mississippi prosecutor’s pattern of excluding African-American jurors, the Supreme Court seemed in broad agreement Wednesday that a black death row inmate’s conviction and death sentence at his sixth murder trial could not stand.

The justices made clear they would not ignore District Attorney Doug Evans’ history as they weighed his decision to excuse five black prospective jurors from inmate Curtis Flowers’ most recent trial.

If Flowers wins, Evans would have to decide whether to try him a seventh time in the shooting deaths of four people in a furniture store in Winona, Mississippi, in 1996. A separate appeal challenging the evidence used to convict Flowers, now 48, is pending in state court.

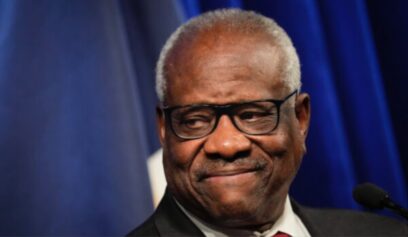

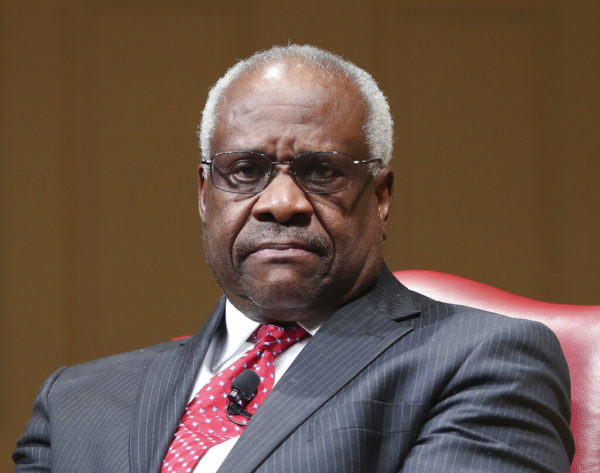

FILE – In this Feb. 15, 2018, file photo, Supreme Court Associate Justice Clarence Thomas sits as he is introduced during an event at the Library of Congress in Washington. Thomas is asking his first questions at Supreme Court arguments in more than three years. Arguments were almost over Wednesday in a case about racial discrimination in the South when the court’s only African-American member and lone Southerner piped up.(AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais, File)

Justice Clarence Thomas, who almost never speaks in court, suggested in questions near the end of the arguments that defense lawyers also care about the racial makeup of juries and concentrate their jury strikes on white people.

“Would you be kind enough to tell me whether or not you exercised any peremptories?” Thomas asked Sheri Lynn Johnson, Flowers’ Supreme Court lawyer.

If so, Thomas wanted to know, “What was the race of the jurors?”

In Flowers’ sixth trial, Johnson said, Flowers’ lawyer excused three white jurors.

But the defense lawyer’s “motivation is not the question here. The question is the motivation of Doug Evans,” Johnson said.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor interjected in an attempt to add more context to why Johnson could not have excused any black jurors because the prosecutor had practically eliminated them all from the options. “She didn’t have any black jurors to exercise peremptories against — except the first one? … After that, every black juror that was available on the panel was struck?” “Yes,” Johnson said.

Thomas did not ask any further questions. But for the most part, Thomas’ colleagues — even his fellow conservatives — focused their questions on Evans’ actions.

“The history of this case, prior to this trial, is very troubling,” said Justice Samuel Alito, who often sides with prosecutors in criminal cases.

Three convictions were tossed out, including one when the prosecutor improperly excluded African-Americans from the jury. In the second trial, the judge chided Evans for striking a juror based on race. Two other trials ended when jurors couldn’t reach unanimous verdicts.

In the sixth trial, the jury was made up of 11 whites and one African-American. The Mississippi Supreme Court has twice upheld Flowers’ conviction.

In selecting a jury, lawyers can refuse to seat jurors for specific reasons, including an unwillingness to impose a death sentence. Lawyers also have a certain number of people they can excuse for no reason at all. These peremptory strikes are at the heart of the Supreme Court case.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Batson v. Kentucky in 1986 set up a system by which trial judges could evaluate claims of discrimination in peremptory strikes and prosecutors’ explanations that have nothing to do with race.

Evans used 41 out of 42 such challenges in five of Flowers’ six trials against African-Americans, Sheri Lynn Johnson, representing Flowers, told the court. The court record is unclear about the other trial.

“The numbers alone are striking,” Johnson said.

Jason Davis, the Mississippi lawyer urging the Supreme Court to uphold Flowers’ conviction, gamely defended Evans’ actions under a barrage of questions, although he acknowledged it might be a good idea if another prosecutor had tried to prove the case against Flowers.

“Can you say that you have confidence in how this all transpired in this case?” Justice Brett Kavanaugh asked.

The record shows Evans had good, race-neutral reasons to keep the five African-Americans off the jury, Davis said.

But several justices sought to pick apart the jury strikes one by one.

Two prospective jurors, one white and one black, were shown to have lied in answering preliminary questions.

Evans seated the white juror, but excused the black woman, who acknowledged under oath to the trial judge that she had lied in an effort to avoid jury service.

“Mr. Evans was willing to give an excuse to this juror and keep him, despite the fact that there was direct evidence that he knew about the case. He was willing to accept the white lie, but not a truthful answer under oath in front of a judge,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor said.

Comparing another white juror with an African-American who was not selected, Justice Stephen Breyer said little appeared to distinguish the two women, apart from race.

Davis pointed out two differences, saying, “I think that’s enough, Your Honor.”

Breyer said: “Well, I do too.” The audience laughed because Breyer meant he thought there was enough evidence to show race was the reason one person was seated on the jury and the other one wasn’t.

Beyond the individual jury strikes, some members of the court returned to the big picture.

Kavanaugh seemed most bothered that Evans’ consistent effort to seat juries with as few African-Americans as possible reflected “a stereotype that you’re just going to favor someone because they’re the same race as the defendant.”

It may have been Kavanaugh’s comment that prompted Thomas’ questions just as the arguments were concluding.

“Would you be kind enough to tell me whether or not you exercised any peremptories?” he asked Johnson, who said Flowers’ trial lawyer had done so.

“And what was the race of the jurors struck there?” Thomas continued.

White, Johnson said. “But I would add that…her motivation is not the question here. The question is the motivation of Doug Evans,” she said.

A decision in Flowers v. Mississippi, 17-9572, is expected by late June.

Associated Press contributed to this story.