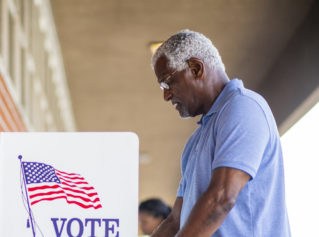

JACKSON, Miss. (AP) — A federal judge says a handful of former Mississippi convicts who are suing to have their voting rights restored can represent everyone who falls into that category.

The ruling this week by U.S. District Judge Daniel Jordan certifying the lawsuit as a class action raises the stakes considerably. A victory by the plaintiffs could restore voting rights to tens of thousands of Mississippians, not just the handful who sued.

There’s still a long way to go in the case. Both sides have asked Jordan to rule without a trial, but the judge could choose to hear witnesses.

The Mississippi Constitution strips the ballot from people convicted of 10 felonies, including murder, forgery and bigamy. The attorney general later expanded that list to 22, adding crimes that include timber larceny and carjacking. The plaintiffs argue disenfranchisement violates the U.S. Constitution because it was adopted with the discriminatory intent of keeping African Americans from voting.

Between 1994 and 2017, about 47,000 people in Mississippi were convicted of disenfranchising crimes, Jonathan K. Youngwood, a New York-based attorney in the lawsuit, has said. About 60 percent of them, or nearly 30,000, have completed their sentences but have not regained their voting rights. Some are still serving time.

African-Americans make up about 38 percent of Mississippi’s population and 36.5 percent of the state’s registered voters. Youngwood said 59 percent to 60 percent of people convicted of disenfranchising crimes in the state are black.

Some states automatically restore voting rights once someone gets out of prison, while others automatically restore rights once someone completes parole or probation. But Mississippi requires people to go through the arduous process of getting individual bills passed just for them with two-thirds approval by the Legislature, or getting a pardon from the governor. A 2016 Sentencing Project study found that 335 people achieved one those between 2000 in 2015.

Republican Gov. Phil Bryant, in his final year in office, hasn’t granted any pardons and has let suffrage restoration bills become law without his signature. Last year, he let four become law without signing them and vetoed a fifth. In a brief veto message April 13, he said restoring the ballot depends on the support of law enforcement “and the person’s ability to show responsibility and honesty after conviction.”

The issue of restoring rights has been gaining traction in historically restrictive states. Florida voters in November overwhelmingly adopted a constitutional amendment that will automatically allow most felons who complete their sentences, about 1.4 million people, to register as voters. This week in Mississippi, the House passed House Bill 637, which will set up a study committee to examine the issue. If the Senate agrees and Bryant signs it, the committee would issue a report by year’s end.