Zimbabwean opposition party supporters march on the streets of Harare. (AP Photo/Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi, File)

JOHANNESBURG (AP) — It will be a first for Zimbabwe’s voters: The name of Robert Mugabe won’t be on the ballot when elections are held on July 30. But the military-backed system that kept the former leader in power for decades, and then pushed him out, is still in control.

That is the conundrum facing a southern African country anxious to shed its image as an international pariah, and to draw the foreign aid and investment needed for an economic revival. The government promises a free and fair vote and the military, whose 2017 takeover led to Mugabe’s resignation, says it won’t stray from the barracks.

Some Zimbabweans, though, wonder how much things have really changed.

They ask whether a political establishment accused of vote-rigging and state-sponsored violence over a generation would accept an election outcome — that is, an opposition victory — that might damage its interests or even expose it to prosecution for alleged human rights abuses. The military’s economic interests include the alleged involvement of security forces in Zimbabwe’s diamond-mining sector, which Mugabe himself once said had been plundered of billions of dollars in revenue.

Then there is the uneasy legacy of the military’s November takeover. It sent euphoric Zimbabweans into the streets to celebrate and was later described as a coup by Mugabe, who quit as impeachment proceedings loomed in parliament. The military intervention was mostly peaceful and tacitly supported by other countries, but critics compared it to letting a genie out of the bottle: Once the military steps brazenly into politics, why wouldn’t it do so again?

“Do you believe that people would risk their lives to carry out a coup, only to hand over power six months later to some unknown person?” Dewa Mavhinga, regional director for Human Rights Watch, asked at a recent forum on Zimbabwe in Johannesburg.

In this scenario, the “unknown person” would be Nelson Chamisa, the new leader of the MDC opposition party whose members were brutalized by ruling ZANU-PF party supporters during violent, fraud-tainted elections in 2008.

The establishment’s man is President Emmerson Mnangagwa, a former vice president and Mugabe ally who rewarded the military’s support with key Cabinet positions for former generals. Mnangagwa, who survived a deadly grenade attack at a campaign rally on June 23, says this election won’t be like those under the 94-year-old Mugabe, who had led Zimbabwe since independence from white minority rule in 1980.

Some things are very different. A record 23 presidential candidates and 128 political parties will participate; there are more than five million registered voters. Western monitors, banned during the Mugabe era, are invited; concerned about military involvement, some are urging senior officers to pledge loyalty now to the election winner, regardless of who it is.

The opposition has held rallies without interference from a police force once quick to break up gatherings of government opponents.

But the idea of accountability for past crimes by suspected state agents has no traction under Mnangagwa, himself linked to the killings of thousands of people in the Matabeleland opposition area in the 1980s. And on Monday, the MDC’s chief election agent, Jameson Timba, said the state election commission had failed to provide an accurate voters’ roll and was trying to manipulate the vote.

“We are sure Zimbabweans will not be railroaded into a sham election,” Timba said.

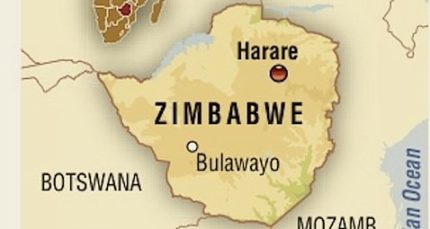

Zimbabweans don’t need to worry about the military, said Vice President Constantino Chiwenga, who was military commander in November when soldiers and tanks deployed in Harare, the capital. The military intervened to back a ruling party faction loyal to Mnangagwa, who had been fired as Mugabe’s deputy, in a feud with a group associated with Mugabe’s politically ambitious wife, Grace.

“There will not be a recurrence, let me assure you,” Chiwenga said last week, according to Zimbabwe’s NewsDay newspaper. “We had created a situation which was bad for ourselves and that will not happen again.”

The military on Wednesday told reporters it will not interfere in the election but will help police with law and order and assist the election commission with transport logistics, which could prove contentious with the opposition.

Spokesman Overson Mugwisi also denied reports that the military has deployed thousands of soldiers to rural areas to campaign for the ruling party, calling them “falsehoods.”

For many Zimbabweans, the grenade attack on Mnangagwa’s campaign rally in Bulawayo last month highlights the country’s political tensions.

The blast killed two security agents and injured dozens of other people, including high-ranking officials, in what the government said was an attempt to assassinate Mnangagwa. Unscathed, the president said the election would proceed as planned and blamed the ruling party faction linked to Grace Mugabe, who is no longer considered a political player.

Tendai Biti, a former finance minister and MDC supporter, said the attack reflected a tendency in Zimbabwe to settle political scores through extra-constitutional means. The same was true for the military takeover in November — an act that never got the scrutiny it deserved, he said.

“We sank our heads in the sand,” Biti said last week in Johannesburg. “We didn’t ask the tough questions.”