FILE – In this June 24, 1968 file photo, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, leader of the Poor People’s Campaign, looks through the barred window of a bus after he was arrested in Washington for leading a group of demonstrators onto the grounds of the U.S Capitol. (AP Photo/Charled Tasnadi, file)

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. (AP) — Thousands of anti-poverty activists have launched a campaign in recent weeks modeled after Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign of 1968. Like the push 50 years ago, advocates are hoping to draw attention to those struggling with deep poverty from Appalachia to the Mississippi Delta, from the American Southwest to California’s farm country.

The latest effort is led by Rev. William Barber of Goldsboro, North Carolina, and Rev. Liz Theoharis of New York City, who are encouraging activists in 40 states to take part in acts of civil disobedience, teach-ins and demonstrations to force communities to address poverty. They say poverty continues to be ignored and only a “moral revival” can bring it to the nation’s consciousness.

The new campaign has also brought new attention to the tumultuous summer of 1968 when the two leading backers of the campaign — King and Robert F. Kennedy — were assassinated two months apart.

Here’s a look at the two campaigns:

THE ORIGINAL CAMPAIGN

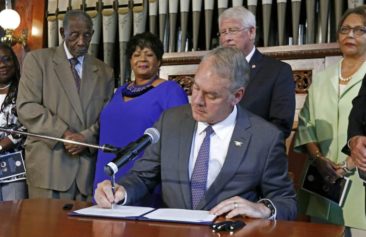

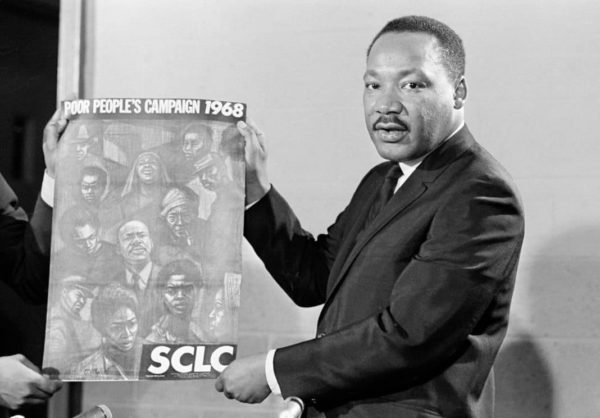

FILE – In this March 4, 1968 file photo, civil rights leader Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., president of the Southern Christian Baptist Leadership Conference (SCLC), displays the poster to be used during his Poor People’s Campaign this spring and summer of 1968. (AP Photo/Horace Cort, File)

Before his assassination, King sought to organize a campaign to direct the country’s attention toward poverty. He felt attacking poverty was the next phase of the civil rights movement and the 1968 campaign would push for a guaranteed income, the end to housing discrimination and reducing the nation’s growing trend toward militarism.

At the time, around 13 percent of U.S. residents lived in poverty.

King reached out to Mexican-American, Native American and Appalachia white leaders to build a multi-ethnic, multiracial coalition that would come from their hometowns on “mule carts” and “old trucks” to Washington, D.C., to dramatize the plight of the poor. Following King’s assassination in Memphis, members of the coalition began to fight with each other.

Thousands of poor people set up a shantytown they called “Resurrection City” on the Washington National Mall but became demoralized by racial tensions, a lack of leadership, and eventually, the assassination of Kennedy.

THE REBOOT

Organizers of the 2018 campaign said they wanted to use the 50th anniversary of the 1968 effort to restart conversations around the struggles that poor people continue to face, especially since the U.S. poverty rate is roughly back to around 13 percent. This time, Barber and Theoharis said the campaign won’t be centered solely in Washington and would include events around the country.

For 40 days, demonstrators planned to hold acts of civil disobedience like blocking traffic and refusing to leave public buildings every Monday nationwide. Hundreds of activists, including Rev. Jesse Jackson, have been arrested so far.

Theoharis said the purpose is to build “a season of organizing” to create a long-term movement aimed at restoring the Voting Rights Act, ending gerrymandering, and helping bolster the minimum wage. She said organizers also hope to influence the 2018 midterm elections and the 2020 presidential election.

Because the nation is more diverse than in 1968, Barber said the new campaign also calls for protection of immigrant, LGBT residents and refugees from the Middle East.

THE CHALLENGES

Barber said media coverage of poverty has been ignored and overshadowed by what he calls “Trump porn” — excessive coverage of President Donald Trump’s tweets, the investigation into Russia’s interference in the 2016 U.S. election and the legal fight involving adult film actress Stormy Daniels.

Small newspapers that used to cover poor rural areas like Linden, Tennessee and the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota also have faced cutbacks. Not since Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign have national politicians regularly visited rural, poor areas and focused on poverty in their platforms.

In addition, Barber said many American Christians have ignored the plight of the poor since megachurches regularly focus on the “prosperity Gospel.” Others have been focused solely on abortion and fighting gay rights, he said.

Barber said the multi-faith campaign seeks to reaffirm messages that religious figures like Jesus were primarily concerned about helping the poor and that the country had a moral obligation to tackle poverty. He also promised that organizers plan to pressure for media coverage of U.S.-Mexico border areas like El Paso, Texas, and Native American communities like San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation in Arizona.