A recent study from the New York Equity Coalition found that students of color across the state are denied access to advance placement courses, failing to prepare them for success in college and their career. The state of educational inequality in New York reflects a problem found throughout the nation. (Photo: Army.mil)

Education provides a gateway for opportunity. Those who have access to a better education have better chances for success. While the U.S. education system may position itself as a meritocracy in which those who work hard in a fair system can succeed, in reality the deck is stacked against low-income students and students of color, who do not even have access to advanced courses that will prepare them for college.

A report from the New York Equity Coalition paints a picture of educational inequality in that state, with implications for schools nationwide. The study — “Within Our Reach: An agenda for ensuring all New York students are prepared for college, careers, and active citizenship” — found that some students are held to lower expectations and denied more extensive and demanding course offerings. These inequities are the root cause of achievement and opportunity gaps, the report says, and New York’s future success depends on preparing all students for careers in high demand industries such as computer science and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) fields.

One subject of the report, Toyia, enrolled in Advanced Placement (AP) courses in the best performing high school in the Rochester City School District. While 70 percent of the students in her school are Black and Latino, students in the advanced courses are predominantly white. In other schools in the state, there are no resources available to teach low-income students at a high level of instruction, and some subjects such as physics and computer science may not be offered.

“Across New York State today, our education system denies students of color access to rigorous instruction in a range of courses that will prepare them for success in college, careers, and civic life. But it does not have to be this way,” the report says. “Better, more equitable outcomes — for our society and our economy — are within our reach, and we call on state leaders to fulfill these five vital commitments to our students and our future.”

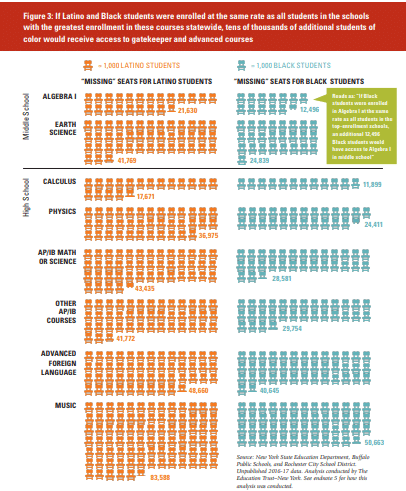

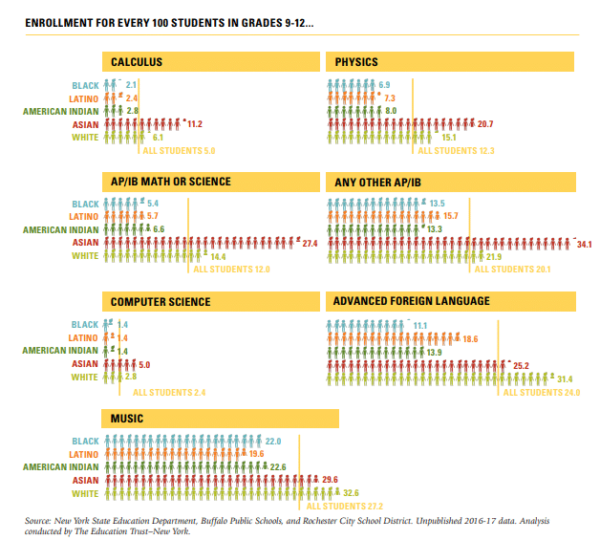

According to the report, students are color are shortchanged in “gatekeeper courses” that open the door for college and career opportunities. In middle and high school, Black, Latino and Native American students are underrepresented in all major subject areas across the board, including AP and International Baccalaureate (IB) programs. This applies not only to math and science staples such as calculus, physics and computer science, but also all subjects, including foreign languages and music. While white high school students in New York are only 8 percent greater in population than their Black and Latino counterparts, they had 230 percent more opportunities to take courses that would earn college credit. If these students of color were enrolled in gatekeeper and advanced courses at the same rate as schools with the highest enrollment in these courses, tens of thousands of additional nonwhite students would have access to these crucial subjects.

Throughout the state, only 34 percent of high schools teach computer science, and whites disproportionately benefit. Since 80 percent of high schools in low-need districts offer computers, only 36 percent of white students attend a school that does not offer computer science. However, 60 percent of Latino students and 62 percent of Black students are enrolled in a school that does not offer computer classes.

Black and Latino students are less likely than whites to attend schools that offer these game-changing subjects, as they often attend high-need school districts where such opportunities are unavailable. For example, 34 percent of Black students and 30 percent of Latino students in the 7th and 8th grade — 41,451 students — attend schools where Algebra 1 is unavailable. This rate is over three times the rate for white students. Meanwhile, 24 percent of Latino high school students and 30 percent of Black students — 83,441 students — have no access to AP or IB math or science courses, as opposed to only 11 percent of their white peers. In low-need school districts, 91 percent of high schools offer six or more advanced courses, compared to 19 percent of high schools in large cities, 18 percent of New York City high schools, and 11 percent of schools in high-need rural districts.

Further, Black and Latino students are denied access to these gatekeeper courses even when they attend schools that offer them. Compounding the situation, they are twice as likely as white students to attend a school that does not have a school counselor to help them prepare for college and decide which courses to take.

The results of the New York study reflect a nationwide phenomenon. Research from Pennsylvania State University study revealed that in Pennsylvania, particularly large cities such as Philadelphia, there is reduced access to advanced courses in charter schools, in schools with a student body greater than 50 percent students of color, schools with a large proportion of students in poverty, and those with an enrollment of fewer than 300 students in 11th and 12th grades. Philadelphia schools are less likely to offer advanced courses in English language arts, social studies, mathematics and science than other schools across Pennsylvania.

A 2013 study concluded that over half a million low-income children and children of color are missing from AP courses nationwide because they are not participating at the same rate as other students. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights found that students of color fall behind their white peers in enrollment in high-level STEM courses. Schools segregation among U.S. high schools is a factor, as the more Black and Latino students attending a school, the less likely that school will offer advanced classes. As of the 2015-2016 school year, white students were 51 percent of high school enrollment and were 51 percent of physics enrollment and 58 percent of calculus enrollment, respectively. Black students, who were 16 percent of high school students, were merely 12 percent of physics enrollment, and 8 percent of calculus enrollment. Latino students, who were 24 percent of high school students, were only 16 percent of calculus students and 19 percent of students studying advanced mathematics. Algebra 1 is the gateway subject, and the gap between white and Asian students and their Black and Latino counterparts develops before they enter high school. White and Asian students are disproportionately enrolled in Algebra 1 in junior high school, while Blacks and Latinos are likely to take the course in the 11th or 12th grade, cutting off their chances to take advanced math classes.

Some schools, however, are making strides in reducing the racial gap in advanced courses. For example, Elmont Memorial High School in Elmont, New York, gives students, parents and counselors a voice in deciding which students should take an advanced course, rather than solely relying on prerequisites. Teachers whose students are excelling share best practices with other teachers, and the school dropped a two-year geometry class maintained for low-performing students. As a result, the number of students with an “advanced” distinction on their diploma has increased.

At Achievement First Hartford High School in Hartford, Connecticut, where nearly all students are of color, there is an “AP for all” curriculum in which the average student will take five AP courses before graduation. AF Hartford provides intensive college counseling, tutoring and SAT preparation, and has a goal of having 100 percent of their students accepted into four-year colleges. As a result, U.S. News & World Report recently ranked the school number 3 in the state.

Civil rights groups filed a lawsuit against the South Orange Maplewood School District in New Jersey alleging that tracking — the practice of placing students on separate academic paths based on their academic performance, which education advocates view as the modern-day racial and class segregation over six decades after Brown v. Board of Education — holds back Latino and Black students in their access to college and career preparatory courses. This has led to the district to work on a plan to address the disparity.

One study found that the myth of a meritocracy and hard work and perseverance as the keys to success can cause marginalized students to implode, as self-doubt and risky behavior creep in and children blame themselves for problems out of their control. If you are advantaged and believe the system is fair, there is no issue for you. However, if you are disadvantaged, you may internalize the stereotypes about your racial or ethnic group, possibly leading to low self-esteem and low grades. Schools must ensure they are not contributing to the marginalization and oppression of students of color, and public school teachers, of whom 82 percent are white, must have difficult discussions with students about systems of racial oppression. Educators can play a role in guiding students from “defiant resistance” to “transformative resistance” and helping them develop an understanding of history.

In addition, ethnic studies and culturally relevant teaching have been proven to have a positive impact on academic achievement and attendance for at-risk young people, as a countermeasure to years of Eurocentric brainwashing that have taken a psychological toll on Black, Latino and other marginalized children. Other research has shown that belief in meritocracy — that success and the chance for upward mobility are an issue of what an individual deserves through effort — serves to legitimize existing inequities in grades, ranks and degrees among advantaged and disadvantaged groups.

The consequences of failing to remedy the inequities in a segregated education system are clear, as students of color emerge as a majority of children in America, and the country continues to fail them.