Do ‘Best Cities’ Rankings Whitewash Factors Key to Black Americans? Photo credit: Jane/Getty

Owning a home has long been considered a key part of the American dream. But a home’s value can vary based on its location. As such, buyers and renters are always seeking guidance about the best places to live. To satisfy this demand, many magazines and websites rank U.S. cities using various criteria.

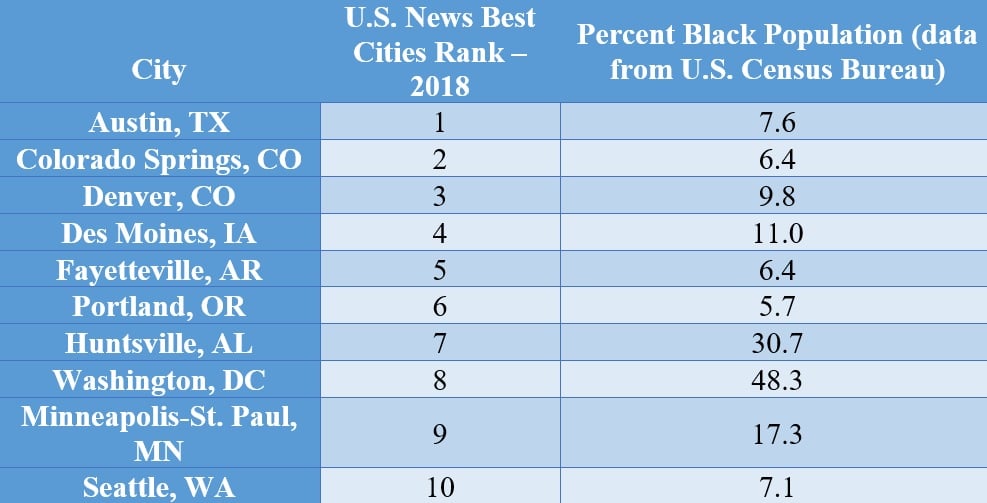

One of the most popular rankings is U.S. News and World Report’s “125 Best Places to Live in the USA.” According to U.S. News, this year’s best cities are Austin, Texas; Colorado Springs, Colorado; Denver; Des Moines, Iowa; Fayetteville, Arkansas; Portland, Oregon; Huntsville, Alabama; Washington, D.C.; Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota; Seattle. These cities make frequent appearances on other publications’ “best cities” rankings as well.

Although these cities are diverse in many ways, they have one thing in common: They are overwhelmingly white. Of the top ten cities, only one — Washington — has a Black population that exceeds forty percent. Seven of the ten have Black populations lower than the national Black population (13.3 %). None are majority Black. If the “best” cities are so disproportionately white, are they truly the best for everyone?

Data from U.S. Census Bureau & U.S. News and World Report

To create its ranking, U.S. News examines factors that include unemployment data, salaries, incomes, cost of living, desirability, and quality of life. When these factors are viewed through the lens of race, it is clear that what makes a city “best” for Black home buyers is not necessarily the same as what makes a city “best” for others.

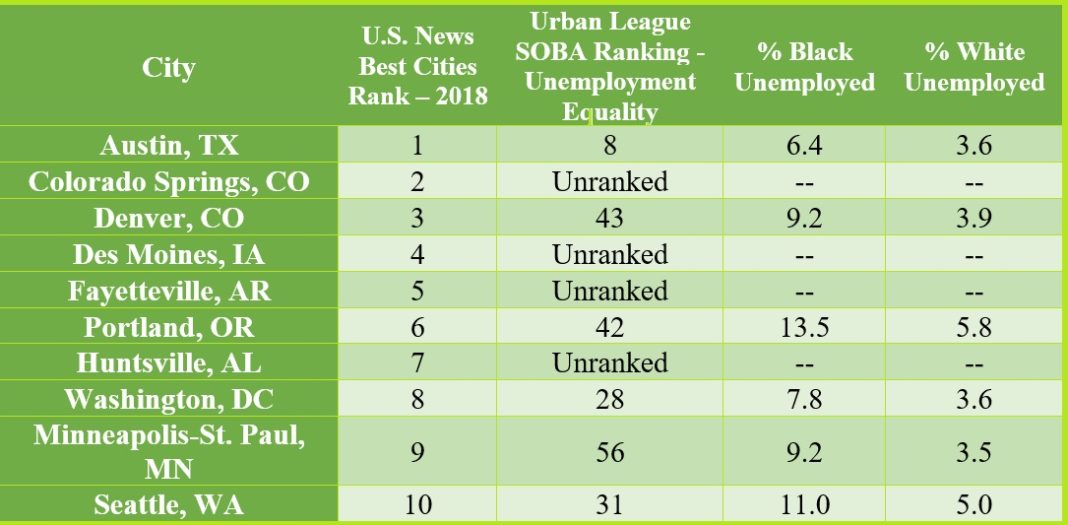

A city without jobs will not attract people of any race. Interestingly, while the cities ranked “best” by U.S. News may have low unemployment overall, Black unemployment may still be a problem If a city’s Black unemployment rate is twice the white rate, is it a good city for African Americans?

In its annual State of Black America report, the Urban League ranks 71 cities based on an “equality index.” Rather than listing raw unemployment data, the SOBA report compares statistics to determine if Blacks and whites are treated similarly. For instance, a city with high unemployment overall could still receive a high ranking if Black unemployment is close to white unemployment. Conversely, cities with low overall employment may receive a low ranking if Black and white unemployment rates are grossly unequal.

Though the SOBA report does not provide data for all of the cities in the U.S. News top ten, when the cities included on both lists are compared, it is clear that the U.S. News rankings overlooked key data relevant to the African-American community.

According to the 2017 SOBA report, the five cities where Black and white unemployment were closest were San Antonio, Texas; Riverside, California; Las Vegas; Jacksonville; and Orlando. Only one of U.S. News’ top ten cities — Austin — made the SOBA top twenty. Austin’s eighth-place unemployment equality ranking far outshines the remainder of the U.S. News list. After Austin, the next-highest ranked cities were Washington (28) and Seattle (31). Some 71 cities are ranked by the Urban League. The rest of the U.S. News best cities were in the bottom half of the SOBA ranking. These lower-ranked cities had high levels of racial inequality.

Data from Urban League, 2017 State of the Black Union Report, available at http://soba.iamempowered.com/sites/soba.iamempowered.com/themes/soba/pdf/SOBA2017-black-white-index.pdf

The data on income inequality paints a similar picture. The 2017 SOBA lists Riverside, San Antonio, San Diego, Tampa, and Lakeland, Florida, as the five cities that are closest in income parity between whites and Blacks. None of them made U.S. News’ top ten.

Data from Urban League, 2017 State of the Black Union Report, available at http://soba.iamempowered.com/sites/soba.iamempowered.com/themes/soba/pdf/SOBA2017-black-white-index.pdf

U.S. News’ top ten best cities fared even worse on income equality than they did on unemployment. None of U.S. News’ top ten cities made the SOBA top ten. However, at least Austin, Washington, and Seattle made the top half of the SOBA ranking. The remaining cities — Denver, Portland, and Minneapolis — all fared worse on income equality than they did on unemployment. In fact, in the SOBA income equality report, Minneapolis, the ninth-best city in the nation according to U.S. News, came in dead last.

Overall, the numbers prove that even when objective factors like unemployment rates and income are considered African-Americans need to dig deeper to determine if a city’s prosperity is shared by all of its residents.

Zillow reports that roughly 45 percent of Americans want to live near public transit, but African-Americans are far more likely than whites to list this as a requirement for a future home. Despite Black buyers’ desire for public transportation, of the top ten cities for public transportation in America, only one, Washington, made the U.S. News top ten. U.S. News did not consider the presence or quality of public transit in its rankings.

Racism affects the objective and subjective factors that may make a city desirable in several ways. First, whiteness affects which neighborhoods and cities are valued in the real estate market. It is well-known that whites prefer to live near other whites, so much so that they will pay a premium to live in predominately white neighborhoods. Because whiteness is so valued, the fact that the best cities are overwhelmingly white is not surprising.

Similarly, not only are the “best” cities white, they are getting whiter. Gentrification has changed the racial makeup of many American cities. Cities that once had Black majorities, like Washington, D.C., have lost them after old residents were displaced by white newcomers. As these cities become whiter, they become more attractive to other whites. As such, the fact that the list of the ten most gentrified cities is a near replica of the top ten “best” cities is unsurprising. However, African-Americans and other nonwhites have reason to reject gentrified cities and neighborhoods. Gentrified areas may be more expensive, may lose their character, or may simply be less welcoming. Gentrified cities are not “best” for all involved.

Data from Governing.com, 2015 Gentrification in America Report, available at http://www.governing.com/gov-data/gentrification-in-cities-governing-report.html

Race also influences a person’s view of crime and policing in their city. While U.S. News considered objective crime data in its analysis, it has been long established that whites are likely to connect blackness with crime. As such, research indicates that when viewing a neighborhood or city that is majority-Black, whites are likely to believe that the neighborhood has a high rate of crime, regardless of the reality. However, the same research found that nonwhites are less likely to do so. People of all races want and deserve safe neighborhoods. Nevertheless, African-Americans’ feelings about which cities are unsafe may differ from whites’.

Turning to the other side of the coin, while a robust police presence may help whites feel safer, because unarmed African-Americans are shot by police officers on a regular basis, African-Americans may feel unsafe around the police, even though they also desire safe neighborhoods. Although African-Americans across the nation are understandably cautious in police interactions, some cities’ police departments pose greater dangers to Black lives than others. In 2015, a study found that in fourteen American cities, 100 percent of those killed by the police were Black. Similarly, many cities have police departments that are severely racially imbalanced. For a ranking to truly reflects where African-Americans feel safe, it must consider the police as well as the criminals.

While U.S. News considered well-being in its analysis, for African-Americans, racism changes the factors that contribute to Black well-being. For example, few African-Americans would be comfortable living in a city with rampant racism. Although it is difficult to objectively determine which cities are the most racist, proxies have been developed. One study used Google searches for the word “ni—r” to examine where racism was thriving. Mapping hate crimes is another tool. Considering a city’s racism changes the “best” city calculus completely. For instance, according to a 2017 report, Portland, Oregon, experienced a 200 percent increase in hate crimes during the previous year — a higher increase than any other city. If U.S. News had considered racism in its rankings, Portland might not have made the list.

Because African-Americans combat racism on a daily basis, home must be a haven from that fight. While whites segregate due to unfounded fears, African-Americans seek out racially balanced neighborhoods and cities so they can retreat from racism. In an interview with CityLab, Dr. Maria Krysan explained that “the desire for more diverse neighborhoods is driven importantly by concerns about discrimination in neighborhoods that are overwhelmingly white. … It is inextricably tied up with past and present circumstances of racial violence and discrimination towards blacks who move into neighborhoods that are all or very predominately white.”

No American city is perfect. All cities continue to grapple with America’s racial past. However, some cities have attempted to heal that past by actively working to, for example, consider the racial impact of their decision just as they consider the financial and environmental impact. Other cities seem content to not only revel in the past but to create new and worse forms of segregation and hostility.

Real estate agents often say, “Location is everything.” For Black families, this saying is true on multiple levels. Because they do not consider our unique needs, African-Americans should view “best” cities lists with caution. What is the “best” for some may be the “worst” for us.