Ryan Coogler’s ground-breaking “Black Panther” movie offers Africans and their US-based descendants, commonly referred to as African-Americans, a model to heal some emotional scars inherited from the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. The relationship between different African groups and their Diaspora is predominantly influenced by racist stereotypes perpetuated by Western media. In spite of the blatant corporatism behind the movie, Coogler creates an alternative image of Blackness and opens up deep-seated issues for discussion. The movie’s global attention provides an opportunity for African descendants to assert control of their narratives, dispel stereotypical perspectives and air long-standing barriers to Pan-African unity.

“Black Panther” is exceptional as a mega budget Hollywood film that showcases the shared heritage of people of African descent. The film depicts Black royalty in a technologically advanced African country with vivid scenes of natural Black beauty and feminine strength. The rich and elegant costumes adorning the Pan-African cast fully represented Africa in its cultural diversity, thereby making audiences across continents relate to the film in a way no other movie of this scale has yet achieved.

Granted it has contentious messages, which villainizes its African-American character and his zeal for a global struggle to uplift Blacks yet exonerates champions of American interventionism; Black Panther nonetheless directly contradicts the persistently distorted Western depictions of Africans and African-Americans. The former are depicted as an utterly helpless, hopeless, starving and warring people that wallow in “sh**hole” conditions, despite resources beneath their feet. The latter are portrayed as violent and unintelligent drug-abusers–a promiscuous group that is too lazy to work despite living in the ‘Land of Opportunity.’ Rarely will Western media detail the historical and institutionally imposed barriers that prevent Africans from benefiting from their resources or African Americans from accessing America’s wealth. The tragedy however, as elaborated by dozens of Black leaders for over a century, is the internalization of those stereotypes.

The internalization of colonial mythologies leads to a marred image of one community towards another, widening the distance between them. Mediums to change stereotypes and properly educate people are few and far in between. People often accept these stereotypes, devaluing themselves and denying their origins, or they reject those stereotypes but attach them to other Black communities/countries. These stereotypes have damaged communities internally, but they also divide communities that could gain from Pan-African cooperation. Anti-Black stereotypes are maintained through ignorance, and ignorance about Africans and African Americans abound.

In the U.S., the disconnection that exists between African-Americans and “Africans” is only a microcosm of the ignorance that makes African descendants from various countries mistrust one another. On one side, some African immigrants are exposed to Western stereotypes and are unaware of the advantages they as “foreign Blacks” have or of the opportunities made available by the blood and tears of past generations of African-Americans. On the other hand, many African-Americans endure a ceaseless “miseducation” campaign that demonizes their black skin and African origin, making some all too glad to deny or belittle anything remotely African.

In Africa itself, diverse ethnic groups don’t know each other, particularly if they are from different countries. They know African-Americans much less. What they know generally comes from their TV screens, and most Africans don’t own a TV. Some Africans will consider African-Americans as their long-lost brothers and sisters, others will see them as white people with Black skin based on their acculturation, and many will have no opinion or don’t care to have one. If Africans dislike any group, it is not some far off community they rarely if ever interact with, it is generally another African ethnic group living within their vicinity–one with which they are vying against for political or socio-economic power. That was true centuries ago when the slave trade amplified ethnic rivalry, and it is true today in the ongoing political crises and conflicts facing a few countries.

A partial solution to this corrosive paradigm is to create positive All-African imagery with thought-provoking themes like Coogler’s Black Panther does. One of the movie’s imperfect but opportune themes was the feeling of abandonment felt by African-Americans. Future stories can now explore the impossibility of African families to rescue relatives who were kidnapped and shipped across the Ocean. An intriguing anecdote is a true story dating from the early 1300s. Before Columbus landed on the Americas, King AbuBakr II of the Mali Empire, Mansa Musa’s direct predecessor, led 2,000 ships to find the end of the Atlantic Ocean. He was never seen again.

Some Africans also express the same sense of abandonment by African-Americans. This is based on another unbalanced portrayal of African-Americans. The publicized stories of successful entertainers lead to a generalized belief of African-Americans as wealthy. Yet the many African-Americans who use their means to improve living conditions in their ancestral home, receive little coverage. Owning the narratives would help to balance these perspectives.

Western media has long disadvantaged Black communities with negative imagery. As content and data grows increasingly vital in our world, the need to control our portrayal is imperative. A conglomeration of Black-owned media outlets, existing on both sides of the Atlantic, can develop constructive images of Black communities. Marvel’s Black Panther has demonstrated that it can be financially viable, and its foundational flaws can be avoided by an independent Pan-African media outlet. Creating such a medium would bring us closer to healing wounds and ensuring future generations are empowered.

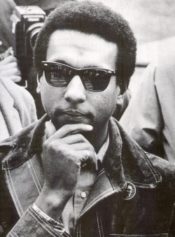

Bokar Ture is an energy and infrastructure project manager. Trained as an economist, he is committed to the development of Africa and its Diaspora. His father was former Black Panther and Pan-African activist Stokely Carmichael b.k.a Kwame Ture.