America is in the midst of an obesity crisis. The most recent statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate that nearly 40 percent of American adults and 20 percent of American children are obese.

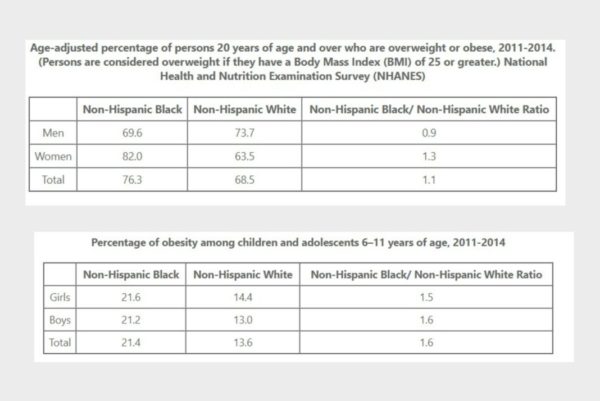

As with some other illnesses within the United States, race shapes the contours of the obesity epidemic. Obesity disproportionately affects African-Americans. According to the CDC, the rate of obesity in African-American adults is nearly 1.5 times that of whites. The same pattern holds for children.

These graphics created by the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health illustrate the racial disparity in the obesity epidemic. Source: DHHS Office of Minority Health, https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=25

Because the African-American community struggles with obesity, it might be shocking to learn that the African-American community also struggles with hunger, or more accurately, food insecurity. According to Feeding America, a nonprofit that fights hunger, “Hunger refers to a personal, physical sensation of discomfort, while food insecurity refers to a lack of available financial resources for food at the level of the household.”

Hunger is a concern for many African-Americans. According to a Feeding America report, 9 percent of white households are food insecure, while 23 percent of African-American households are. The same report reported that the number of African-American children in food-insecure homes is double that of white children. Strikingly, the report found that although there are only 105 counties in America that are majority Black, more than nine out of every 10 of these majority-Black counties are in the top 10 percent of all counties for food insecurity. How can African-Americans suffer from obesity and hunger at the same time? Although this seems paradoxical, the problems share some common causes.

Poverty

The poverty rate in the African-American community is twice that of the white community. Poverty promotes both obesity and hunger.

One surprising connection between poverty and food is transportation. Because supermarkets are not always located in African-American neighborhoods, according to the Food Research & Action Center, “vehicle access is perhaps the most important determinant of whether or not a family can access affordable and nutritious food.” However, poor families often lack personal transportation, depriving them of the ability to travel for healthy food.

When a family is poor, buying the most food for the least money is a critical survival skill. However, research shows that healthy food can be prohibitively expensive for poor families. As a result, to stretch dollars, poor families choose less expensive options. Though this is an economically rational choice, it is horrible for health because the less expensive “junk foods” are loaded with fat, sugar, salt, and calories. Of course, foods with these qualities contribute to obesity.

The Food Environment

Obesity and hunger are both influenced by the food environment. The food environment — the grocery stores, bodegas, and restaurants that are in a neighborhood — influences the ability of neighborhood residents to eat healthy food.

Unfortunately, many Black neighborhoods are “food deserts.” Food deserts are areas that do not have ready access to healthy foods such as fresh produce because they lack supermarkets or grocery stores. Because there are no major stores, those in food deserts rely heavily on convenience stores and fast-food restaurants for food. However, these places feature food that is rarely fresh and often processed and unhealthy.

The connection between obesity and food deserts is clear: people without healthy food options will eat whatever is easily available. The connection between hunger and food deserts is not as obvious but is still present. According to FRAC, many people in food-insecure households are in a constant “feast or famine” situation. Because they cannot always afford food, many poor people overeat when food is available. But, because the food in these neighborhoods is often unhealthy, the “feast” part of the cycle can lead to obesity.

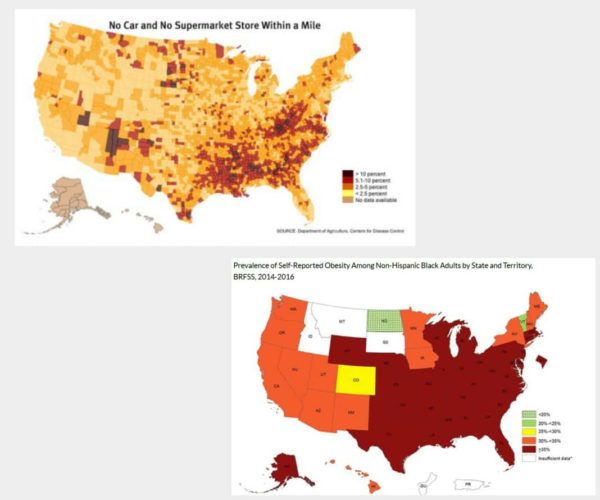

These maps show the overlap between food deserts and obesity. Map 1 (upper left) shows the prevalence of food deserts. Map 2 (bottom right) shows the rate of Black obesity. Note the overlap between the two, particularly in the Southern states.

Source for Map 1: http://americannutritionassociation.org/newsletter/usda-defines-food-deserts

Source for Map 2:

https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html

The Neighborhood Environment and Exercise

According to research compiled by FRAC, poor neighborhoods lack many of the amenities that encourage people to exercise, such as parks and recreational facilities. These areas may also have unkempt sidewalks — or no sidewalks — such that even walking is made more difficult. Safety is another issue. Neighborhoods that are poor may have crime, traffic, blight, or other safety issues that make physical activity unwise even when it is possible. With such obstacles, it is not surprising that some residents forgo exercise altogether.

Here again, there is a connection between hunger, obesity, and poverty. FRAC’s research notes that one side effect of food insecurity is a lack of physical activity. Logically, since one needs food to fuel the body, a person that is not eating a healthy diet — or not eating at all — frequently will lack the energy to exercise.

Racism-Induced Stress

Stress plays a role in both food insecurity and obesity. Food insecurity and stress are closely tied. Research shows that food insecurity causes stress, which in turn inhibits weight loss. Although obesity is commonly thought of as caused by a lack of willpower, more recent research has found that stress is one of the many factors contributing to obesity. Even those that are actively trying to lose weight may find their progress stalled in times of high stress.

For African-Americans, racism makes every day a day of high stress. The American Psychological Association notes that there are many types of stress. Nearly everyone will experience acute stress, which is the type of stress that occurs when a person experiences a major life change, such as moving. This stress is high at the time, but it eventually subsides. Chronic stress, by contrast, lasts for long periods of time, even years.

While anyone can experience stress, stress is not distributed equally among races. Compared to whites, the APA notes that African-Americans and other non-whites experience high levels of chronic stress, much of it due to racism. In fact, psychologists coined the term “acculturative stress” to describe the special stress that comes from knowing that one is not part of the dominant culture and trying to navigate that reality.

What Can Be Done?

No matter the causes, one thing is certain: obesity and food insecurity cause major problems for the health of the African-American community. Obesity is related to hypertension, diabetes, stroke, heart disease and other severe ailments. The African-American community suffers from these diseases at rates higher than their white counterparts. Until our community is healthy, these diseases will continue to impact our health and life expectancy.

While obesity and hunger in the Black community are large problems, they are not unsolvable. Several campaigns have taken steps to improve the food environment in cities across the nation. Support of such campaigns and other efforts to bring supermarkets, farmers markets and other fresh options to neighborhoods in need is a good start. Moreover, cities can be lobbied to improve the physical environments of their neighborhoods to make them more conducive for exercise.

The poverty and racism that underlie much of the food issues in the Black community are more difficult to address. Although poverty will not end soon, programs that help to alleviate food insecurity for the poor such as WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) and SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) should receive support at all levels of government to address the “feast/famine” cycle experienced by so many. And although African-Americans did not cause racism and are not responsible for ending it, a community committed to engaging in a regimen of healthy self-care to deal with racism might help reduce racism-induced stress.