Source: theblackevolutionary.wordpress.com

Although it is common knowledge that modern-day Nazis in America draw their inspiration from Nazi Germany, far less widely known is that the Jim Crow South inspired Hitler. For all the outrage over the rise of neo-Nazis, white supremacists and the alt-right — and the legitimization of these groups in the halls of power in Washington — ultimately the underpinnings of Nazi ideology are homegrown and very American. The Nuremberg laws — which segregated Jews and discriminated against them in all aspects of life, stripped them of citizenship, banned interracial marriage between Aryans and Jews, and laid the groundwork for genocide — originated in the Jim Crow segregation laws. While the white nationalists in Charlottesville, Virginia, looked to Nazi Germany as their guide, the original Nazis used the United States as their template.

In his book “Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law,” James Q. Whitman, a professor of comparative and foreign law at Yale Law School, delves into the neglected history of Nazi Germany borrowing from American race law. It is unfathomable for some that the United States, regarded as the beacon of democracy and liberty, would play and integral role in the development of Germany’s fascist, genocidal legal system. However, the two societies were very similar, as Whitman detailed in his book:

In the 1930s Nazi Germany and the American South had the look, in the words of two southern historians, of a “mirror image”: these were two unapologetically racist regimes, unmatched in their pitilessness. In the early 1930s the Jews of Germany were hounded, beaten, and sometimes murdered, by mobs and by the state alike. In the same years the blacks of the American South were hounded, beaten, and sometimes murdered as well.

In the early 20th century, the United States was the world’s foremost racial jurisdiction and the leader in overtly racist citizenship and immigration policies, which explains why Germany would want to emulate elements of its legal system. In “Mein Kampf” (1925), years before he seized power, Hitler said the United States was “the one state” that had progressed in creating a healthy racist society.

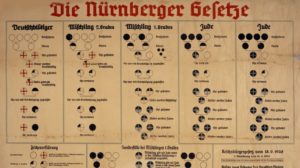

A copy of the Nazi-issued Nuremberg Laws. (Credit: Fine Art Images)

The Nuremberg Laws were introduced on September 15, 1935. Two specific laws are worth noting with regard to U.S. influence: The Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor.

The Reich Citizenship Law revoked citizenship for Jews. America, with its second-class citizenship and segregation for Black people, inspired the Germans. Moreover, the United States had people such as Native Americans and Filipinos who lived in the country and its territories, yet were non-citizens, and other minority groups such as Japanese, Chinese and Puerto Ricans who were subjected to second class or colonial status. The Reich had a particular interest in second-class citizenship in America, and decided to strip Jews of their German citizenship and recategorize them as “nationals.”

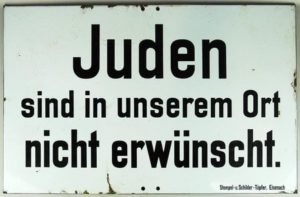

Sign: “Jews are unwelcome in our town” (Source: Deutsches Historisches Museum)

Under the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, marriages between Jews and German citizens were forbidden, as was extramarital sexual relations between the two groups. Punishment for breaking the law included imprisonment and hard labor. The law was enacted on the grounds that “the purity of German blood is essential to the further existence of the German people.” These German restrictions on intermarriage and sexual relations reflect the influence of the American anti-miscegenation laws which were on the books in 30 of the 48 states, including outside the South, and were the most severe laws of their kind, with draconian criminal punishment for interracial marriage.

Source: NoSue.org

Whitman noted that the American legal system of racial classifications was more severe than what the Nazis were willing to codify. “Moreover, the ironic truth is that when Nazis rejected the American example, it was sometimes because they thought that American practices were overly harsh: for Nazis of the early 1930s, even radical ones, American race law sometimes looked too racist,” Whitman writes. For example, under the Nuremberg Laws, a Jew was defined as someone with at least three Jewish grandparents. In contrast, many states in the United States, particularly in the Jim Crow South, had the ”one drop rule” to determine who was Black.

In his book, Whitman discusses the Nazi preoccupation with “race defilement” and the harm of “mixing” German and Jewish blood, particularly German women and Jewish men. The Nuremberg Laws were designed to prevent prevent “any further penetration of Jewish blood into the body of the German Volk [people].” The author characterizes the extent of American influence over the Nazi legal system as “depressing,” though not surprising to those who are familiar with early 20th century U.S. race history. “It is a familiar fact that much of America was infected with the same racial madness: as the Nazi literature noted, there were many Americans who simply ‘knew’ that black men regularly raped white women. American courts, as German authors were aware, were capable of delivering matter-of-fact holdings such as ‘the mixing of the two races would create a mongrel population and a degraded civilization.'”

Southern states would file briefs with the U.S. Supreme Court that were indistinguishable from Nazi propaganda, while Senator Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi sounded very much like a Nazi philosopher when he spoke of the horrors of white racial decay due to mongrelization, offering that “one drop of Negro blood placed in the veins of the purest Caucasian destroys the inventive genius of his mind and palsies his creative faculty.”

The American anti-miscegenation laws were not eradicated until 1967 with the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Loving v. Virginia, which invalidated laws against interracial marriage that were still on the books in 16 states. In Loving, the Supreme Court noted that according to the Virginia courts, the purposes of the Virginia Racial Integrity Act of 1924 — that state’s anti-miscegenation statute — were “‘to preserve the racial integrity of its citizens,’ and to prevent ‘the corruption of blood,’ ‘a mongrel breed of citizens,’ and ‘the obliteration of racial pride,’ obviously an endorsement of the doctrine of White Supremacy.”

“The racially pure and still unmixed German has risen to become master of the American continent,” wrote Hitler in Mein Kampf, “and he will remain the master, as long as he does not fall victim to racial pollution.” The U.S. Immigration Act of 1924 impressed Hitler, with its preference for Northern European immigrants and restrictions for people from Southern and Eastern Europe, and outright bans for all others. The Nazi leader found the American immigration policy consistent with the Nazi Party Program of 1920.

German propagandists hoped to normalize Nazi policies by using the U.S. as a model, assuring fellow Germans that America also had racist politics and policies, such as “special laws directed against the Negroes, which limit their voting rights, freedom of movement, and career possibilities.” One Nazi official even justified the practice of lynching: “What is lynch justice, if not the natural resistance of the Volk to an alien race that is attempting to gain the upper hand?”

The strong influence of Jim Crow on Nazi Germany is a testament to the potency and toxicity of American racism. Germany enacted strict laws after World War II banning Nazi symbols such as the swastika and banning hate speech that encouraged racial/religious violence. In America, the symbols of white supremacy remain, including Nazi emblems, and the Confederate flags and monuments that promote Black oppression. These symbols of American racism endure because of a failure to acknowledge a history of racial injustice against Black people, and a legal system that allowed it to happen.