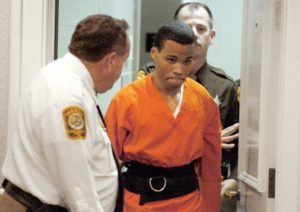

Lee Boyd Malvo pleaded guilty and was given two life sentences for the murder of Kenneth Bridges and the shooting of Caroline Seawell in 2002. (Mike Morones/The Free Lance-Star via AP)

BALTIMORE (AP) — A U.S. Supreme Court decision triggering new sentences for inmates serving mandatory life without parole for crimes committed as juveniles has had a far greater effect: The ruling is prompting lawyers to apply its fundamental logic — that it’s cruel and unusual to lock teens up for life — to a larger population, those whose sentences include a parole provision but who stand little chance of getting out.

The court in January 2016 expanded its ban on mandatory life without parole for juveniles to more than 2,000 offenders already serving such sentences, saying teens should be treated differently than adult offenders because they’re less mature, prone to manipulation and capable of change. The court found that all but the rare juvenile lifer whose crime reflects “permanent incorrigibility” should have a chance to argue for freedom one day, and dozens serving mandatory terms have since been re-sentenced and released.

But legal challenges also are being argued on behalf of offenders sentenced to life with parole for crimes they committed as teens — a population totaling some 7,300 inmates nationwide, according to Ashley Nellis at advocacy group The Sentencing Project.

“Even states that do have parole, it doesn’t give a lot of reason for hope,” Nellis said. “The Supreme Court was very clear to say that age-related factors need to be considered at re-sentencing or parole review, but the feedback we’re seeing is that those factors aren’t being considered.”

Other courts are applying the 2016 ruling to those whose life-without-parole sentences weren’t mandatory or were negotiated as part of a plea deal. In Florida, more than 600 inmates are potentially eligible for new sentences because court decisions there require a new look at anyone serving life for crimes committed as minors — even if their sentences were optional or included the possibility of parole.

The Supreme Court has not ruled on these other circumstances, but some state courts have. In January, New Jersey’s Supreme Court ordered new sentences for two former teen offenders with de facto life terms. One was serving 110 years, with parole eligibility after 55 years; the other had 75 years, with parole eligibility after serving 68. The court noted both defendants would “likely serve more time in jail than an adult sentenced to actual life without parole.”

The number of years inmates must serve before parole eligibility varies by offense and state: In Tennessee, a lifer must serve 51 years. In Texas, 40. Lifers could qualify for a hearing after 10 years in Michigan, but that doesn’t mean they’ll get one. In 44 states, parole boards are appointed by governors, and review processes vary greatly. Some boards review prisoner files without in-person interviews. Some states specify factors to consider; others allow significant discretion.

If a prisoner is denied, he’ll likely wait several years for another chance and sometimes isn’t told why.

Chester Patterson, 63, has been behind bars for 45 years in Michigan. At 17, he fatally shot a store clerk during a robbery. He got life with the possibility of parole after 10 years. Patterson has earned degrees, completed a substance-abuse program, worked in the library and avoided disciplinary tickets. He’s also been denied parole at least five times, according to records. Each time, the board sends a notice that says, “no interest.” He’s awaiting a decision after his most recent hearing in April.

“I am not that same 17-year-old kid. I will never commit another crime again,” Patterson wrote to The Associated Press. “I caused a terrible tragedy for which I will always be sorry and shameful. What more can I say to the family? I have been here for almost a half of a century, and the parole board is still saying no.”

His case isn’t unique. In Florida, a state Supreme Court ruling last year said that juvenile offenders who were eligible for parole must be re-sentenced to ensure they have a real opportunity for release. The ruling came in the case of Angelo Atwell, who got life with the possibility of parole after 25 years for a murder he committed in 1990 at age 16. When it came time for Atwell to argue for his freedom, the state calculated his presumptive release date as 2130 — 140 years after sentencing.

“While technically Atwell is parole eligible, it is a virtual certainty that Atwell will spend the rest of his life in prison,” the justices wrote, and his sentence, “virtually indistinguishable from a sentence of life without parole, is therefore unconstitutional.”

Atwell awaits a new sentencing hearing.

Iowa’s highest court in 2013 found that the governor didn’t comply with the U.S. Supreme Court when he commuted the life-without-parole sentences of 38 juveniles to life with the possibility of parole after 60 years, because they wouldn’t be eligible until they surpass their life expectancy. “Oftentimes, it is important that the spirit of the law not be lost in the application,” the court wrote.

More legal challenges have been filed in North Carolina, Illinois and Missouri, among other states.

Maryland, Oklahoma and California are the only three states that require the governor to sign off on parole recommendations for lifers. Last year, the American Civil Liberties Union sued Maryland, arguing that a life-with-parole sentence doesn’t afford prisoners a meaningful shot at release because governors for two decades haven’t approved any petitions. Even Parris Glendening, the former Maryland governor who set the standard when he declared in 1995 that “life means life,” says the system he designed is dysfunctional.

“What happens with lifers now, I had some responsibility. And I say that not with pride, but with regret,” Glendening told the AP. “What we’re finding now is people who are juveniles … they are now aging in prison, are probably a threat to no one at this stage. It’s a question of humane treatment: Is it humane or cruel and unusual to have someone sitting in jail at 50, 60, 70 for an offense committed half a century ago?”

Maryland’s parole commission in October began reviewing all 271 lifers who committed crimes as juveniles, according to commission chairman David Blumberg. As of May, the commission had reviewed 76 cases: 45 have been scheduled for additional hearings, 20 were referred for psychological risk assessments and nine were refused parole. Two asked for postponements. None has been released.

Gov. Larry Hogan said he and his team take the process seriously.

“They meet with the inmate. … They talk with the victim’s families and witnesses and spend months and months,” he said. “And in a few cases, I was convinced that people had served their debt to society and deserved a second chance, and several of them were people that were convicted at a very young age and had served long, long sentences and had been model prisoners and really rehabilitated themselves.”

But Hogan hasn’t approved any parole bids for juvenile lifers. The commission, on average, has recommended fewer than two prisoners serving life sentences for parole per year since 1995, according to public defender James Johnston, who says the state’s system contravenes the essence of the Supreme Court rulings.

Johnston is at the forefront of a battle over whether even Maryland’s juvenile life-without-parole sentences fall under the high court’s mandate for review. Prosecutors say no, because the sentences aren’t mandatory.

In June, Johnston argued before a Maryland judge that Lee Malvo, one of the D.C. snipers who terrorized the Washington area for a month in 2002, deserved a new sentence. He was 17 and pleaded guilty to murder charges in Virginia and Maryland. He received life without parole in both states, but a Virginia judge recently ruled the term unconstitutional and ordered Malvo re-sentenced.

In Maryland, prosecutors say the judge made an informed decision. A ruling is pending.

Another of Johnston’s clients, Robert Boyd, was sentenced to life at 16 for his role in a home invasion that turned deadly in Baltimore. Boyd was the lookout, standing watch on the porch. The man who fired the fatal shot was acquitted at trial.

In prison, Boyd earned degrees, stayed out of trouble, coached boxing. For years, he unsuccessfully applied for parole. But in April 2016, he was released on probation after Johnston convinced a judge to reopen the case, arguing that Maryland’s system didn’t afford Boyd a meaningful chance at parole and was therefore unconstitutional.

“Maryland inmates serving life sentences are forced to resort to the court system instead of the parole system, because the parole system offers no real chance of release,” Johnston said. “The focus has shifted from … taking advantage of whatever is offered to you behind bars. That no longer results in release or even gets you closer to the door. Instead, you’ve got to find a reason to get back in front of a judge.”

By the time Boyd was released, after 34 years behind bars, even Brian Murphy, the prosecutor who tried the case in 1982, offered to testify on his behalf.

“It was not the intention of anybody back then that guys like this wouldn’t get paroled,” Murphy said. “It doesn’t sound fair or legal.”