When you walk into a courtroom, there is the common perception that the individual wearing the flowing robe and sitting on the elevated bench before you— the one yielding the gavel who everyone rises for — is the most powerful person in the American criminal justice system. Think Supreme Court. Think how landmark decisions in our nation’s history, from Plessy v. Ferguson to Brown v. Board, were sealed at the resounding end of a gavel. Think how lawyers on both sides must ask permission to approach the bench or how they can be tossed in jail if a judge feels they’re acting inappropriately.

Yet, this common perception is actually a misperception. The prosecutor is, by far, the most powerful actor in our justice system, wielding authority the judge does not. In fact, it’s hard to overstate the power and role of the prosecutor in our country’s criminal justice system. Prosecutors determine who to charge with a crime and which charges are filed. They decide when to drop charges, when to plea bargain and how prosecutorial resources are allocated and employed. In capital cases, they have power over life and death as they decide which charges carry a penalty of death. Prosecutorial powers are generally described as “nearly absolute.”

One former prosecutor is working hard to get his colleagues to wield this power in a more constructive and progressive fashion.

“Doing what I am doing now, working with prosecutors to better understand their mindset, I find they are mostly very nice people but are not being incentivized to think creatively,” says Adam Foss, a former prosecutor for the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office in Boston.

In 2016, Foss co-founded Prosecutor Impact, an advocacy organization seeking to highlight the need for prosecutors to provide alternatives to incarceration after giving a wildly popular TED talk on reinventing the role of the criminal prosecutor. Foss feels given our adversarial and highly politicized system of justice, many prosecutors operate in a “very fear-based and risk-adverse” fashion. And when the vast “majority of prosecutors are white, that plays out in a very specific way” which “is why the criminal justice system looks the way that it does.”

After contending that current metrics of performance like number or severity of convictions are counterproductive, Foss drives home the impact of the superior power of prosecutors. “Every day, people are brought to the doorstep of our criminal justice system and the one person that decides whether or not a person enters is the prosecutor.” In deciding how to charge those who do enter, he explains, “they dictate how that person will spend the rest of their time in that system. I can charge someone with felonies or I can charge them with a misdemeanor. I can charge them with mandatory minimum sentencing and, thereby, take all of the power away from the judge, or I can charge in a way where I have undue influence in the plea negotiations” so the judge is basically “rubber stamping what I do.”

“In Manhattan, last year, judges agreed with prosecutor recommendations on bail 100 percent of the time,” Foss says. “So, the prosecutor really is the lynchpin to this entire thing.”

Given the ongoing problems and racial disparities in mandatory minimum sentencing and the plea-bargaining process, such prosecutorial discretion carries particular weight for African-Americans as it is rife with potential for abuse and error. The endless quest to appear “tough on crime” and secure as many convictions as possible minimizes accuracy, proportionality and empathy. The National Registry of Exonerations reports an “estimated 43 percent of wrongful convictions arise from misconduct involving prosecutors, police, investigators, and other officials.” Between 1989 and 2012, there were over 1800 documented cases of persons convicted and later exonerated.

The Center for Prosecutor Integrity revealed that the most common types of ethical violations committed by prosecutors were failure to disclose evidence, use of inadmissible or false evidence, plea bargain misconduct, witness harassment, mischaracterizing evidence and “vouching” (when an attorney suggests or tells a jury they should believe a witness because the attorney believes that witness.)

Foss notes that, after “tough on crime policies put more weapons in our toolkit and shifted discretion away from judges and into our hands,” most prosecutors “were just never trained properly how to use that discretion.”

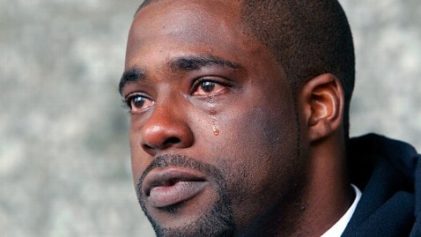

Prior to his own training for the most powerful position in the justice system, Foss faced a few prosecutors himself. And, unlike now, no one was celebrating him for it. Adopted at an early age by a white blue-collar couple, Foss had a few minor brushes with the law growing up before experiencing the first of several arrests for fighting and selling weed at age 19. Despite being African-American, his parents’ skin color would make the difference. “Because of my ‘white privilege,’ I was saved from the justice system and put back in college,” Foss says.

Initially considering a career in medicine, Foss changed direction upon an internship at his college’s legal services office. He left school and worked as a paralegal for a business litigation defense firm where, though “hating what I was doing, I could see the power of the law.” At the time, clarifies Foss, “none of this was aimed at social justice” but was more about “making as much money as possible.” Accordingly, he went on to law school to become an entertainment lawyer until fate stepped in once more in the form of an internship with a Boston court. There, Foss recognized “the gravity and size of the problems affecting people that look like us” and that “I had a stake in it and could do something about it.”

He’s been doing just that ever since. In 2008, Foss graduated cum laude from Suffolk University Law School, where he was awarded the prestigious Book Award from the Massachusetts Black Judges Conference. Four years later, the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office gave him the Brian J. Honan Award in recognition of both his work in the courtroom and his service to Boston-area communities. In 2013, Foss won the Access to Justice Section Council Prosecutor of the Year Award from the Massachusetts Bar Association and, not long after, was appointed to the state’s Juvenile Justice Advisory Committee by Gov. Deval Patrick.

More recently, Foss founded and continues to operate a reading program based out of the Suffolk County DA’s office. “My vision of prosecution is much more than what we do in the courtroom” he explains, as it “has a lot to do with preventing crime. And one thing that we know is a huge indicator of crime is how kids are reading at a third-grade level.”

Prosecutors read to kindergarteners on Mondays and follow these same children through third-grade before cycling back to kindergarten and repeating. The program, which started out with four prosecutors, now has over 40. In addition to closing the achievement gap, Foss says, the program’s other benefits include “combatting implicit bias because prosecutors are in public schools and communities” they were previously unfamiliar with, and both sides are “being exposed to people they’ve been conditioned to not respond well to and develop relationships with them early on.”

Foss also co-founded the Roxbury CHOICE Program, an effort to remodel the probation process from its current punitive intent into a transformative experience with the participation of the court, the probation department and the District Attorney’s Office. Operating out of the Roxbury Division of the Boston Municipal Court, CHOICE enables youths on probation to take on educational and vocational goals as an alternative to incarceration.

Last year, because of his work, Foss was one of a group of prosecutors from across the country invited to a New York City dinner with singer/activist John Legend. After hearing Foss speak, Legend — a vocal critic of mass incarceration — and his manager, Ty Stiklorius, pledged a large sum to support Foss’ organization, Prosecutor Integrity. Because of the demands of the new organization, which seeks to cultivate cultural competency, integrity and compassion among prosecutors, Foss decided to leave the Suffolk District Attorney’s Office.

“He very well could influence national policy,” says Professor Robert Proctor, a criminal defense attorney and clinical instructor in the Harvard Law School’s Criminal Justice Institute. Proctor first met Foss in a Boston court when the latter was a third-year law student training to become a defense attorney and encouraged him to consider becoming a prosecutor. Proctor feels Foss’ criminal defense sensibilities enabled his understanding of both sides of judicial policy while heightening his empathy for defendants. “He became very involved in the community and, particularly, with people of color and young adults in terms of outreach programs under the auspices of the Suffolk County DA’s Office.”

“Adam had a totally different approach to prosecution,” continues Proctor, noting Foss was not “gung ho about taking defendants to trial and hanging them as high as we can. He was more about trying to find alternative ways to resolve cases and this message was not always in sync with the DA’s office he worked for.”

Nonetheless, this different approach to prosecution is taking hold in America.

“In November 2016, something happened that has never happened in our democracy,” Foss says. “Five incumbent DAs were voted out of their offices because of their ‘tough-on-crime’ policies.” Altogether, he reports, a total of “14 out of 25 incumbents lost their seats” during a “year of only 25 DA elections.” Since “95 percent of incumbents traditionally win their elections, this was a major event.”

While many have failed to recognize the significance of this event, given the outcome of the controversial 2016 presidential race — and the importance of the organized and growing public backlash against tough-on-crime policies in states throughout the nation — Foss clarifies the stakes going forward.

“In 2018, there will be over 1000 prosecutor elections around the country,” he says. “This is going to be the most important year for criminal justice reform if we focus on this prosecutor issue.”