When generalizing about millennials, many don’t bother to differentiate between race, class or gender, erasing the very real divide faced in particular by Black millennials. The culturally myopic idea that we’re all the same and can be analyzed under the same umbrella is rooted in the same troubling ideology that views the white Western middle-class reality as the shared standard for everyone. It’s impossible for that to lend itself to a qualitative analysis when even within the Black millennial population, there are multiple existing intersections that create different realities for different young adults.

Although there are challenges that millennials face that have cross-cultural significance, such as the price of college tuition rising faster than inflation, 51 percent of millennials being underemployed and fears of never being able to get out of debt, that does not mean that the problem is equally felt by each racial group in a similar way. The truth is, Black millennials are facing problems that differentiate them from their peers.

A BYP100 report authored by Jon Rogowski, an assistant professor in the Department of Government at Harvard University, and Cathy J. Cohen, a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, specifically outlines how America’s legacy of systemic racism has affected Black youths in various aspects, leaving them far more vulnerable to socioeconomic hardships than their peers of other ethnicities.

BYP Announcement: The First Ever 'Black Millennials in America' Report has been Released! https://t.co/A7taiZglkw pic.twitter.com/Wr000Aw4ar

— Black Youth Project #BYP (@BlackYouthProj) November 4, 2015

America’s legacy of workforce discrimination has undoubtedly influenced young Black men and women’s employment status. When the national unemployment rate hit 5.3 percent, it was 9.6 percent for millennials, but significant variation existed within different millennial groupings. Unemployment rates for Black millennials of different age ranges are noticeably higher than Latino millennials and almost double the rate of white millennials within the same range. Just to drive home how troubling this is, the worst year of white unemployment over the past decade (12 percent in 2010) is better than the best year of Black unemployment (14 percent in 2007) over the same time period.

A scarcity of available jobs combined with America’s legacy of housing discrimination and redlining has greatly contributed to the fact that Black millennials experience poverty at rates far higher than their peers. In 2013, 32 percent of young Black people lived in poverty, compared to 21.3 percent of young Latinos and 16.9 percent of young white people.

Young Black men and women also are incarcerated at twice the rate of Latinos and far higher than the rate of whites. For example, in 2013, 1,092 out of every 100,000 18- and 19-year-old Black males were locked up, compared to 412 of Latino males and 115 white males of the same age. While the raw numbers are less for women, the ratio is still troubling. In the same year, 33 per 100,000 18- and 19-year-old Black females were incarcerated, compared to 17 Latino females and 7 white females.

Young Black men and women must deal with being targets of America’s prison-for-profit pipeline while also struggling to find work and elevate themselves out of poverty. But, when they do, other forms of discrimination await them in professional and academic settings. Black high school and college graduates are not only twice as likely to be unemployed as white graduates, but Black college grads also carry higher student debt.

To make matters far grimmer, the earning power of young Black graduates still lags far behind that of their white peers. In 2013, Black households headed by someone with a college degree earned $52,147 on average, while white households headed by someone with a college degree earned $94,351.

Here’s where the colorblind millennial assumptions truly fall apart: White millennials are simply getting more substantive assistance from their parents than Black millennials. A study on the racial wealth gap notes, “Single whites are much more likely to possess positive net worth, most likely due to benefits from substantial family financial assistance, higher-paying jobs and home ownership.” The study indicates that as much as 20 percent of their wealth can be attributed to formal and informal gifts from family members, most likely parents. Black and Latino millennials were far less likely to receive this type of help. One-quarter of baby boomers also provided their millennial children with money to pay their expenses so they could save money. Black and Latino millennials were far less likely to receive this type of help.

These economic realities are compounded by research from Clark University that reveals 80 percent of parents of Black millennials expect to be financially supported by their children, even though their kids earn less than their white peers. Black millennials also are far more likely to be asked by family members to borrow money. So, even when Black millennials graduate, find a good job and earn a decent wage, they face familial economic strains, while white millennials typically enjoy familial economic assistance. In a nation with a pronounced racialized gap, where employment, economic and law enforcement discrimination all still exist, we mustn’t erase how those issues disproportionately effect young Black adults.

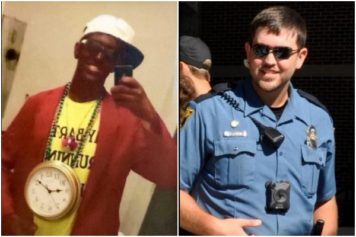

We also mustn’t erase the positives that Black millennials contribute to our community and to American society as a whole. It is Black millennials who cultivated and continue to lead the Black Lives Matter movement, which has highlighted and pushed forward the fight against police brutality and systemic racism.

It is Black millennials who have raised the bar of educational attainment compared to older Black generations in terms of high school graduation rates and attaining a college associate’s degree or higher. A recent study concluded that Black women are now the most educated group in the United States.

And it is young Black women who are taking their financial futures into their own hands, who are the driving force behind African-American women becoming the fastest-growing group of entrepreneurs in the nation.

The challenges that face this generation are plentiful, but they’re also unique, and attempting to lump them into the larger millennial group without proper context and nuance is to discount our difficulties and erase our successes.