Has cinema become the de facto leader of the Black community? It would certainly seem so. After watching months of the new president entertain a Black “Celebrity Apprentice,” litany of entertainers, rappers, former athletes, the son of MLK and, most recently, Pastor Darrell Scott, there’s a nigh-palpable feeling that there’s a void. The community’s likely unanimous pick, Barack Obama, has long since handed Trump the keys and absconded to a Fortress of Solitude in Hawaii and other warm climates. In the wake of that departure, the sense of a Black public figure that captures our collective will, brilliance and imagination has been lacking.

Our likeliest ones are aging and have now more often functioned as symbolic figures to rally behind and uphold out of reverence; when Trump attacked John Lewis via Twitter on MLK Day weekend, the reaction was not only viral, but reverential in tone. He’s done so much for us. Respect our history. Respect our struggle. There’s a feeling that as those sort of pillars disappear — either from our imagination or the earth — the bench is looking decidedly thinner. There’s some hope in Ta-Nehisi Coates, but his sweet spot seems to be more the pen than the public pulpit, an impassioned, parsing thinker who distills the id of our struggle but is not interested in being the face of the Black movement so much as our brilliant moral scribe.

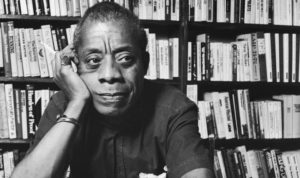

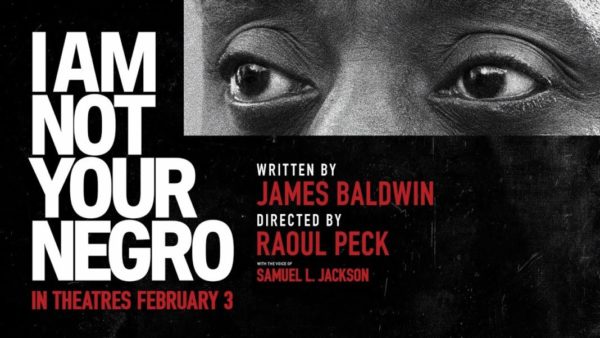

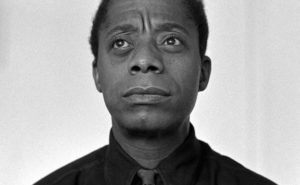

Recent theatrical releases, though, have managed to imprint the African-American narrative, adamantly stating our collective humanity to the mainstream. Ava Duvernay’s “13th” restated our systemic oppression, “Moonlight” our humanity and “OJ: Made in America” our injustice. This week, Raoul Peck’s vision of James Baldwin’s “I Am Not Your Negro” arrives in theaters to restore our conscience.

Voiced by Samuel L. Jackson, “Negro” is Peck’s reminder of Baldwin’s unfinished work, which bears a striking similarity to America’s own unfinished work in race relations and justice. The documentary is caustically poignant today. In its dissection of American, white-hot violent racism and steadfast apathy or aloofness to racial animosity, his words and the film’s images — detailing our struggles pre-, during and post-civil rights — function as a spoken-word performance, and over 90 minutes, the audience is essentially forced to binge-watch cyclical oppression and white indifference. Baldwin reminds us of as much in the film; through archival footage of Baldwin’s public appearances, Peck reminds us of the number of times Baldwin walked into the maw of white spaces, conscience intact, in a way that’s a stark parallel to the circus acts that have visited Trump.

It’s hard to say so definitively, but it’s not a long shot to suspect that Baldwin would reject an offer to sit with Trump. As a queer African-American male with outspoken views about America’s steadfast white nationalist agenda, he is the exact antithesis of what this administration would want to hear from. “I Am Not Your Negro” reminds us of the cost of such resistance, too; much of the documentary underscores the literal and figurative cost of being an active resister of American nationalism. It’s important to remember how inhospitable the times were for Baldwin and other Blacks. He foresaw the necessity to retreat to Paris, the distance chilling his perspective about America but also likely feeding the mania for the unfinished work that the documentary revolves around, a dissection of how that resistance cost us not only the lives of everyday Black citizens but also our biggest heroes at the time — Medger Evers, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Baldwin, in his guest lectures at university halls, couch-side with Dick Cavett and others, knew the stakes: Liberation would not happen without blood and bodies. And even as our bodies filled the coffers of white supremacy, the tithe was never enough.

“I Am Not Your Negro” challenges and accuses the limitations of white imagination to Black liberation. Amidst the protests, both past and present, Peck parallels the tone deafness of the mainstream, white Christian community, detailing how in the grips of our televised, bloody struggle to gain base-level recognition in the country, cloistered spaces like Hollywood continued to spin a counter-narrative that denied the resistance. The documentary makes use of films like “The Pajama Game” with Doris Day, Gary Cooper and the other celebrities of that era, all blithely creating work that reinforced an innocent, aloof, bucolic vision of America, where white smiles, love and bodies moved freely about the country, rain or shine. It’s telling that in 2017 so little has changed in this regard; as the 2017 Oscar nominees were announced, alongside of harrowing black narratives — “Fences,” “Moonlight” and “Hidden Figures” — there is the presumed leading horse of “La La Land,” a film that has its two white costars literally dancing above Los Angeles.

But maybe that doesn’t matter. Two weeks ago, as a legion of pink pussyhats, safety pins and sloganeering signs clogged the arteries of cities and social media feeds, a national conversation was sparked about the nature and motivation of protest in the form of a Black woman holding up a sign “Don’t Forget White Women Voted For Trump,” while nonchalantly enjoying a lollipop, three white women stand perched above the fray taking selfies, a harsh distillation of what Baldwin repeatedly underscored. There were many captions, think pieces and hashtags attached to the image already, but it’s helpful to add Baldwin’s own words to this image: “History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we literally are criminals. I attest to this. The world is not white. It never was white. It cannot be white. White is a metaphor for power.” Ironically, the Black woman pictured carries the last name “Peoples.” Imagine that.