Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is recognized throughout the world as a civil rights champion. However, many of us underestimate Dr. King’s increasing focus on economic rights — and more important, economic empowerment — during his final years. A closer look at Dr. King’s final five years demonstrates the point.

For example, the 1963 Birmingham Campaign, which many people remember because of the Children’s Crusade and the police force’s use of water hoses and dogs, was not only about desegregating public facilities. The campaign also was about creating equal employment opportunities for Black residents in the downtown stores, which didn’t mind taking Black money but refused to help create Black income.

Similarly, the 1963 March on Washington also had a broader focus than many think. After all, the full name of the march was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. In addition to the civil rights topics that we usually associate with the march, such as desegregated public accommodations, desegregated schools and voting rights, the list of demands included:

- A massive federal program to train and place all unemployed workers on meaningful and dignified jobs at decent wages

- A national minimum wage act that will give all Americans a decent standard of living ($2.00 an hour was the target at the time.)

- A broadened Fair Labor Standards Act

- A federal Fair Employment Practices Act barring discrimination

It’s worth noting that the $2-per-hour minimum wage that the movement was seeking in 1963 is worth slightly more than $15 per hour in today’s terms. Thus, there is a direct connection to today’s campaigns that fight for $15 an hour, as well as to policy debates regarding raising the federal minimum wage to a living wage (and local government versions of such increases). In a very real sense, we are still fighting for the wages that Dr. King was demanding in 1963.

Fast forward past a Nobel Peace Prize, voting rights and other organizing efforts, and we come to 1966 and the Chicago Campaign, which targeted several issues, including housing segregation. The campaign led to an agreement that included a promise from mortgage bankers to end discrimination in mortgage lending, but there was little follow-through. The campaign also included Operation Breadbasket, through which demonstrations and consumer boycotts were used to pressure several major companies to expand employment opportunities for Black workers and contract opportunities for Black-owned businesses. The operation is estimated to have won 2,000 new jobs worth $15 million a year in new income for Chicago’s Black community in the first 15 months of its operation.

Today, racial discrimination in mortgage lending nationwide continues to be common, sometimes resulting in disproportionate loan denials and other times resulting in Black borrowers receiving loans at higher interest rates. And since homeownership is one of the largest components of household wealth, this disparity accounts for a significant portion of the racial wealth gap — a gap that has produced White wealth that is roughly 13 times the size of Black wealth ($144,200 vs. $11,200, respectively). Similarly, Black unemployment (7.9 percent) remains roughly twice the rate of White unemployment (4 percent), which has been the case ever since the federal government began tracking the statistic in the 1950s.

The following year, Dr. King and the SCLC launched the Poor People’s Campaign, arguably one of the most frequently mentioned topics when people think about Dr. King and economic empowerment. However, it’s important to note that, although the campaign’s goals included legislation for full employment and guaranteed income, King viewed the campaign as more than just a demand to address the symptoms of poverty. He saw it as a mechanism to address and transform the root causes of poverty. He saw the campaign as part of a wider revolution and social transformation that would challenge and change the very structures that create such poverty.

According to the Census Bureau, in 2015, 22.9 percent of Black families lived below the poverty line, representing only a modest gain since 1969, when 30.9 percent of Black families were in poverty, and the Black poverty rate remains more than twice as high as the White poverty rate. Clearly, the transformation that Dr. King called for did not take place, and our need to demand such change is more important now than ever.

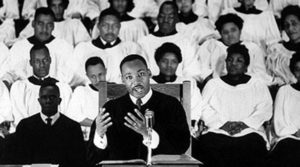

The need for such a transformation was one of the topics Dr. King spoke about in his 1967 address to the SCLC convention: “Where Do We Go From Here.” In addition, in that speech, Dr. King spoke unequivocally about the need for Black people to gain both political and economic power. King argued, “The plantation and ghetto were created by those who had power, both to confine those who had no power and to perpetuate their powerlessness.” And although he maintained that the struggle must always be based on love, he declared that, “love without power is sentimental and anemic.” Thus, his increasing focus on economic issues was not just about fairness and equality, but about power and “the strength required to bring about social, political and economic change.”

Given the goals of the Poor People’s Campaign, along with Dr. King’s evolving thoughts regarding power, it is no surprise that he decided to visit Memphis to support striking sanitation workers. During his first visit related to the strike, King delivered a speech in which he challenged the community to escalate the struggle, and he called for a general work stoppage beyond the sanitation workers. “If you let that day come, not a Negro in this city will go to any job downtown. And not a Negro in domestic service will go to anybody’s house or anybody’s kitchen.” Thus, Dr. King was making a bold statement regarding the power of Black labor; essentially, the city could not function without the labor of Black bodies.

However, Dr. King’s strategy for utilizing Black economic power was not limited to labor. Dr. King continued to encourage the Black community to use its collective economic power to pressure business. During his second visit, Dr. King delivered what would turn out to be his final speech, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” memorable for its prophetic vision of the movement’s eventual victory and the possibility that Dr. King would not be alive to see it through. What’s less discussed is that in this speech, King pointed out that “Collectively, we are richer than all the nations in the world, with the exception of nine,” and that the Black community had “an annual income of more than $30 billion a year, which is more than all of the exports of the United States and more than the national budget of Canada.” King advised Black Memphis to withdraw economic support from companies that did not support the striking sanitation workers, hiring Black workers and other elements of the civil rights agenda.

Moreover, in the same speech, Dr. King also promoted the strengthening of Black institutions. He called on the Memphis community “to take your money out of the banks downtown and deposit your money in Tri-State Bank,” the Black-owned bank, and to support the Black-led savings and loan association. He also encouraged community members to support the Black-owned insurance companies (of which there were 6 or 7 at the time). King’s point was, “We begin the process of building a greater economic base, and at the same time, we are putting pressure where it really hurts.”

Dr. King’s point remains valid today. Yes, Black wealth and income remains unacceptably low, while unemployment and poverty remain tragically high, especially in comparison to White America. Nevertheless, Black buying power is expected to reach “$1.4 trillion by 2020,” according to research done by the University of Georgia’s Selig Center for Economic Growth and reported by The Atlantic. That “is so much combined spending power that it would make Black America the 15th-largest economy in the world in terms of Gross Domestic Product.”

This is why recent calls for targeted boycotts, such as the Injustice Boycott, calls to support Black banks and mechanisms to increase support for Black businesses, such as the Backing Black Business site launched by Black Lives Matter, all have the potential for significant impact. However, for this to take place, the Black community must fully understand the strategies that Dr. King was calling for and implementing, and we must be fully committed to carrying those strategies out.