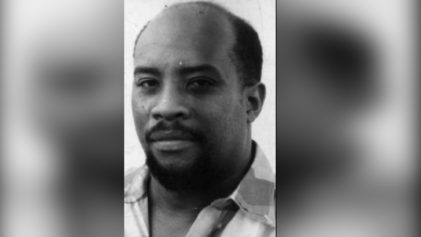

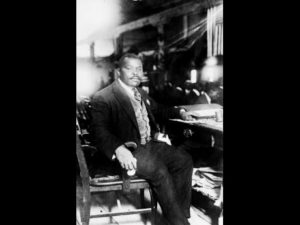

Marcus Garvey

It ought to be a matter of great embarrassment to Jamaica that a petition urging Barack Obama to pardon this country’s first national hero, Marcus Garvey, on his trumped-up 1923 conviction for mail fraud, couldn’t muster the 100,000 online signatures required for the White House to formally recognize the request and provide an initial response to it.

Worryingly, the effort didn’t fail just marginally. By the time the petition closed yesterday after its 30-day window on the White House’s website, it was 74,268 shy of the threshold. Or, put another way, the 25,734 persons who signed the document represented only 26 percent of the requirement.

For this, the Jamaican Government and its institutions must bear much of the blame, assuming that the Holness administration was sincere – which we believe it was – in supporting the demand for Garvey’s pardon. But others, too, failed.

Marcus Garvey, we recall, is Jamaica’s first designated national hero, for his achievements in lifting the consciousness and esteem of black people globally. But Garvey’s accomplishments loom larger when viewed through the prism and context of his period.

He was born within half a century of West Indian slavery. By the early 1920s, based in the United States, his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) had become a global organisation, with several million members in more than 40 countries. His ideas of black liberation had a profound impact on the thinking of the first generation of independence leaders in Africa and the Caribbean.

But Mr Garvey was brought down by America’s systemic opposition to black nationalism and the systematic efforts of its law-enforcement agencies and some of his black competitors. Indeed, it is now widely accepted that the fraud charges of which he was convicted in connection with his Black Star shipping line were concocted.

There are some who believe that Jamaicans should be unconcerned with how others cast the island’s hero. But it has long been Jamaican government policy, and the position of the Garvey family that the conviction represents an unwarranted stain on his character that should be removed.

In this context, acceptance of a presidential pardon is interpreted not as an agreement to guilt from which there is forgiveness, but as the easiest, and politically practical, way for America’s leader to acknowledge the wrong and to, by executive authority, seek to right it.

Read the full commentary here.