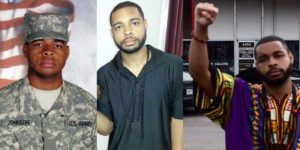

Micah Xavier Johnson

Micah Xavier Johnson — the accused gunman in last week’s Dallas shooting ambush that left five police officers dead and seven wounded, along with two injured civilians — has been widely condemned within and without the Black community for the incident, which is the greatest single killing of law enforcement since 9/11.

For the most part, African-Americans are not sympathetic to the alleged actions of Johnson, who was himself killed by a police bomb robot, according to reports. At the same time, voices within Black America have also expressed surprise, given the levels of rage among Black people over police violence, that such an incident had not occurred sooner.

Given the continuously intense dosages of oppression, deprivation, humiliation and murder to which Black people have been subjected, one would expect violent reactions to said oppression. Some Black voices have gone against the grain and have expressed an understanding of — and even a sympathy for — the alleged sniper’s motives. Violent reactions to racial oppression for the sake of liberation are nothing new, nor are they pretty or suitable for polite company. These are difficult issues to discuss, and yet they represent a reality that must be addressed. Later this year, the film “The Birth of A Nation,” which depicts the Nat Turner slave rebellion, will thrust this historical concept into the mix and put it to the test.

In an opinion piece in The New York Times, Michael Eric Dyson condemned Johnson’s alleged acts, expressing concern that he hijacked a peaceful protest, and in the process, the debate about the legitimate grievances of Black Americans.

“We, black America, are a nation of nearly 40 million souls inside a nation of more than 320 million people. And I fear now that it is clearer than ever that you, white America, will always struggle to understand us,” Dyson wrote. “We don’t want cops to be executed at a peaceful protest. We also don’t want cops to kill us without fear that they will ever face a jury, much less go to jail, even as the world watches our death on a homemade video recording. This is a difficult point to make as a racial crisis flares around us.”

Black people in America are a nation within a nation. There is a long history of revolutionary actors, of individuals and smaller groups within a nation who have taken matters into their own hands and have brought about change in the pursuit of justice, human rights and freedom through bloody violence. Are they heroes or are they villains? Often, today’s terrorists are given a makeover, becoming tomorrow’s heroes, leaders and statesmen and women. And when people find their backs against the wall, history has shown they will do what they must to resolve that back problem.

George Washington and the American founding fathers were considered terrorists by the British in their day. That Independence Day in 1776 was not meant for the enslaved Black folks. And while the white colonialist power structure was always intent on monopolizing the apparatus of violence, violent Black revolts in resistance to white oppression were carried thorough, however infrequently.

For example, Denmark Vesey, one of the founders of the AME church, was hanged in 1822 along with 34 others for being a ringleader in a slave revolt in Charleston, South Carolina. Vesey had preached a liberation theology of God’s deliverance of the people of Israel from bondage in Egypt.

In 1831, Nat Turner orchestrated a violent slave rebellion in Virginia, enlisting the support of 40 or 50 slaves, and killing 55 men, women and children in the process. Turner became a potent symbol for the Black power movement of the 1960s.

Throughout Africa and the African diaspora, anti-colonial liberation movements have employed violence. In an example of the largest slave rebellion in the history of the Western Hemisphere, Haiti became the first post-colonial independent Black republic as a result of a revolution against the French. For having the nerve to violently rise up against oppression, Haiti has paid a hefty price over the years.

Looking at the freedom struggle in apartheid-era South Africa, Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress were branded as terrorists. Although known as a statesman and man of peace in his later years, and father of the post-apartheid South Africa, Mandela had a revolutionary past that embraced militancy and armed struggle.

In response to the violent responses of Black people to their oppression, white power has reserved the right to impose violence, and own the violence by forbidding others to engage in it. And the oppressed always were expected to accept this. This, after all, is part of the power dynamic of white supremacy, in which whites are the purveyors of violence as a right, while Blacks who engage in violence do so under penalty of imprisonment or death. This is why, under the slave codes, it was not a crime for whites to kill Black people or rape Black women. This was even encouraged. However, a Black person accused of killing a white person or raping a white woman met a swift and certain death.

Whole classes of crimes were invented solely with Black folks in mind, with punishment that applied only to Blacks, because whites were unable under law to commit those offenses. In other words, it wasn’t just about the violence itself, but who was committing it — and against whom. This is why the U.S. disarmed Japan after World War II by means of enacting a new constitution, even as America — who had dropped two atomic bombs on Japan and placed Japanese-Americans in concentration camps — continued to amass nuclear weapons in an arms race with Russia.

“If you’re not ready to die for it, put the word ‘freedom’ out of your vocabulary,” Malcolm X once said. He believed that once Black people were willing to take an uncompromising step and bring about freedom “by any means necessary,” that they would not be alone. Malcolm reflected on the violence of revolutions:

There’s been a revolution, a black revolution, going on in Africa. In Kenya, the Mau Mau were revolutionaries; they were the ones who made the word “Uhuru” [Kenyan word for “freedom”]. They were the ones who brought it to the fore. The Mau Mau, they were revolutionaries. They believed in scorched earth. They knocked everything aside that got in their way, and their revolution also was based on land, a desire for land. In Algeria, the northern part of Africa, a revolution took place. The Algerians were revolutionists; they wanted land. France offered to let them be integrated into France. They told France: to hell with France. They wanted some land, not some France. And they engaged in a bloody battle.

So I cite these various revolutions, brothers and sisters, to show you — you don’t have a peaceful revolution. You don’t have a turn-the-other-cheek revolution. There’s no such thing as a nonviolent revolution. [The] only kind of revolution that’s nonviolent is the Negro revolution….

The white man knows what a revolution is. He knows that the black revolution is world-wide in scope and in nature…How do you think he’ll react to you when you learn what a real revolution is? You don’t know what a revolution is. If you did, you wouldn’t use that word.

A revolution is bloody. Revolution is hostile. Revolution knows no compromise. Revolution overturns and destroys everything that gets in its way. And you, sitting around here like a knot on the wall, saying, “I’m going to love these folks no matter how much they hate me.” No, you need a revolution.

Fast forward to today and the aftermath of Dallas. While no political leaders or public figures would dare to call Micah Johnson a hero, some Blacks and radical whites have characterized him as a hero on on social media.

Micah Xavier Johnson died for US. He died for OUR revolution. And it’s time to make his death meaningful so let’s make change

— Rahim (@HecticHEEM) July 8, 2016

RIP MICAH XAVIER JOHNSON! May your death not be in vain! https://t.co/RbDxQteLR3

— nick washington (@girlsugar) July 8, 2016

RIP MICAH XAVIER JOHNSON…for taking your own stand against the injustices…though your STAND wasnt PEACEFUL.i feel you brother

— perkBERRIshade (@b_lasalleperk) July 8, 2016

To some degree Micah Xavier Johnson is a hero to the blackman. I’m also tired of all the peaceful protests only to be killed like flies

— Black Lantern (@Vic_Scientist) July 8, 2016

Micah Xavier Johnson is a hero #BlackLivesMatter

— R.Nixon (@PlayerPlayer24) July 8, 2016

He stood on what he believed &He sacrificed hisself for his people. The mans a Patriot. RIP Micah Xavier Johnson ✊? https://t.co/ap15NEosIs

— R.I.P BIG PHIL (@_MadeInDuval2) July 8, 2016

Shoutout to Micah Xavier Johnson for doing what we all wanted to do.

— GMG $avvy (@tresavagefoe) July 8, 2016

Rip Micah Xavier Johnson, we need warriors like you

— POSITIVEN3RGYRL (@fuckRaychiel) July 8, 2016

Rip Micah Xavier Johnson True Hero ?

— HEFF (@TylerHEFFNER) July 8, 2016

Whatever the sentiments and reactions to the acts he is accused of committing, Johnson — who was upset about the killing of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge and Philando Castile outside Minneapolis — was methodical and had a system in place, a discipline, if you will. While in Poland for a NATO summit, President Obama referred to the ambush shooting as “vicious, calculated and despicable,” adding that, “We also know when people are armed with powerful weapons unfortunately it makes attacks like these more deadly.”

“This was a mobile shooter that has written manifestos on how to shoot and move. He did that. He did his damage. But we did our damage to him, as well,” said Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings, as reported by the Los Angeles Times. “This was a well-planned, well-thought-out, evil tragedy,” added Dallas police chief David Brown.

As Newsweek reported, Johnson posted on Facebook denouncing the lynching and brutalization of Black people.

“Why do so many whites (not all) enjoy killing and participating in the death of innocent beings,” Johnson wrote.

According to the U.S. Army, Johnson, 25, had served as a private first class in the Army Reserve from 2009 to 2015. Further, he was deployed to Afghanistan from November 2013 to July 2014. According to officials, he had “bomb-making materials, ballistic vests, rifles, ammunition and a journal of combat tactics in his home,” according to The New York Times, as well as a journal describing a tactic in which a gunman keeps moving in order to confuse the enemy. Apparently, he honed his military skills, maintained a training regimen, and conducted military exercises in his backyard. And he was prepared to kill.

Micah Johnson reminds us that the responses to oppression can be violent, just as the oppression itself — allowed to fester for years, unabated and unaddressed — is most definitely violent. It may be difficult to swallow, but it is real.