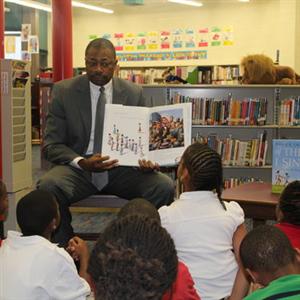

St. Louis PS Superintendent Kelvin Adams reads to elementary students/ Slps.orgSt. Louis Public Schools will end suspensions for students in preschool through second grade. The young children will receive in-class counseling and instruction on classroom expectations as an alternative, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Special Administrative Board member Richard Gaines said the action was an effort to decrease the region’s alarming number of out-of-school suspensions.

“We’re trying to keep more of them in [school] so we can work with them, so we can address issues with these children rather than sending them out,” Gaines said.

Changes will go into effect for the next school year.

The state of Missouri came under fire last spring when a study revealed that Black elementary school children were more likely to be suspended there than in any other state.

The study, conducted by UCLA’s Center for Civil Rights Liberties, found that Black students throughout Missouri were suspended more often than white students at a rate twice as high as the national average. But the numbers out of St. Louis Public Schools were most damaging to the state. Some 29.1 percent of the district’s elementary students were suspended in the 2011-2012 school year.

CCRL Director David Losen noted that “effective” schools did not have high numbers of suspensions.

“Effective schools keep kids in school and have a high amount of instruction time,” Losen told the Post-Dispatch in 2015.

Losen also confirmed the widely reported statistic that Black boys often receive the toughest punishment of all.

He told the Post-Dispatch, “What we’re coming to understand as a culture, there’s a tendency to perceive a situation involving Black males as being more dangerous than it actually is.”

Losen went on to say, “This type of large disparity impacts both the academic achievement and life outcomes of millions of historically disadvantaged children, inflicting upon them a legacy of despair rather than opportunity.”

Experts have referred to this phenomenon as the school-to-prison pipeline.

St. Louis Public Schools made significant changes a year after the study. In addition to the ban on suspensions, the district is offering therapy to elementary students with behavioral problems this year. Next year, drug treatment will be available to students with drug offenses. Teachers will be trained year-round on student trauma and ways to deal with the resulting behavior.

Superintendent Kelvin Adams said, “We just think it’s the right thing to do. What we’re trying to do is not say that our kids are bad, but that our kids need support.”