“She started vomiting with diarrhea,” Desir recalls. “I made oral rehydration for her, nothing worked. She died at 3 in the morning.”

She never made it to a hospital or clinic and so probably wasn’t counted as a cholera victim.

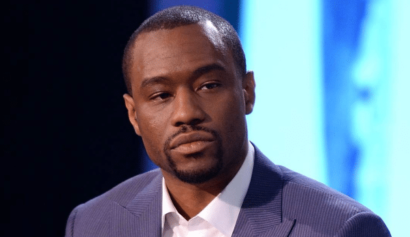

After burying his mother, Desir, a third-year student at Haiti’s University of Agronomy Sciences, nearly died of cholera himself.

Desir and his mother are among at least 770,000 Haitians struck down by cholera since late 2010 — almost 8 percent of the population. More than 9,200 have died. It’s the largest and most explosive cholera epidemic in modern times.

Since cholera is now endemic in Haiti, the epidemic continues. So far this year the disease has struck more than 7,800 people and killed nearly 100.

And there’s new evidence that the toll from Haiti’s ongoing cholera epidemic is significantly higher than official tallies suggest. Meanwhile, survivors appear to be making headway in a legal and public relations campaign to gain compensation from the agency they blame for introducing cholera to the island nation: the United Nations.

A study, which appears this month in “Emerging Infectious Diseases,” indicates Haiti’s official count of cholera cases and deaths are a big understatement. A house-to-house survey in four communities — two urban and two rural — has uncovered nearly three times more cholera deaths in the first six months of the epidemic than officially recorded. In some hard-to-reach villages, researchers found, cholera killed 1 in every 20 residents in the early months of the outbreak.

“It is likely that many other areas in the country suffered similar rates of death occurrence,” says Dr. Francisco Luquero of Doctors Without Borders, an author of the study.

It’s widely believed that — possibly just a single soldier — brought cholera to Haiti during deployment from Nepal, where cholera is a perennial threat. Before Haiti’s epidemic began in October 2014, the disease hadn’t been known in Haiti, this hemisphere’s poorest country.

Poor sanitation at a U.N. camp for peacekeepers allowed cholera-contaminated sewage to enter a tributary of Haiti’s largest river, the Artibonite. Within days, hundreds of people downstream, like Jean-Clair Desir and his mother, were falling ill. The disease subsequently spread to the entire country.

Read more at www.npr.org