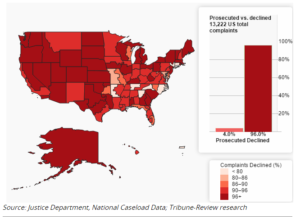

A look at various jurisdictions across the U.S. tells the story. For example, in the Northern District of Georgia, in which Atlanta is located, federal prosecutors declined to prosecute nearly 80 percent of police brutality cases. In the Southern District of Georgia (Augusta and Savannah), prosecutors declined nearly 99 percent of the time. Federal prosecutors in the Eastern District of Missouri, which includes St. Louis and Ferguson, declined such cases nearly 82 percent of the time. Meanwhile, that rate is 70 percent in the Southern District of New York (New York City), 95.5 percent in the Northern District of Illinois (Chicago) and 92.4 percent in the Central District of California (Los Angeles).

The federal law — Title 18, Section 242 — dates back to 1866. It was part of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, a Reconstruction-era law which was designed to protect the civil rights of emancipated slaves of African descent. The law provides penalties of up to life in prison or the death penalty for “Whoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, willfully subjects any person in any State, Territory, Commonwealth, Possession, or District to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States…”

Acts committed under color of law “include acts not only done by federal, state, or local officials within their lawful authority, but also acts done beyond the bounds of that official’s lawful authority, if the acts are done while the official is purporting to or pretending to act in the performance of his/her official duties,” according to the Justice Department website. The statute is meant to include police officers, prison guards and other law enforcement officials, judges, care providers in public health facilities, and other public officials. The crime need not be motivated by racism or other form of animus based on color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status or national origin of the victim.

Moreover, the requirement that the officer must “willfully” intend to violate someone’s civil rights emanates from a 1945 Supreme Court case called Screws v. United States. Like the 1866 statute, the Screws decision arose from problems involving Black people in the South, specifically the brutal beating death of Robert Hall, 30, a Black man by police in Baker County, Georgia in 1943. M. Claude Screws was the sheriff of Baker County. The incident arose after one of Screws’ deputies seized Hall’s pistol for no reason, and Hall went to Sheriff Screws’ house demanding its return. Subsequently, Screws sent two officers to Hall’s home on trumped up charges for stealing a tire, and those officers lynched him in the middle of town square, crushing Hall’s skull:

Hall, a young negro about thirty years of age, was handcuffed and taken by car to the court house. As Hall alighted from the car at the court house square, the three petitioners began beating him with their fists and with a solid-bar blackjack about eight inches long and weighing two pounds. They claimed Hall had reached for a gun and had used insulting language as he alighted from the car. But after Hall, still handcuffed, had been knocked to the ground they continued to beat him from fifteen to thirty minutes until he was unconscious. Hall was then dragged feet first through the court house yard into the jail and thrown upon the floor dying. An ambulance was called and Hall was removed to a hospital where he died within the hour and without regaining consciousness. There was evidence that Screws held a grudge against Hall and had threatened to ‘get’ him.

When local officials would not intervene, federal prosecutors used the Reconstruction-era law to charge the officers for killing a Black man. Unbelievably for the Jim Crow South, Screws and the officers were tried and convicted, fined and imprisoned for the crime.

Ultimately, the high court vacated the convictions of the white officers based on the vagueness of Section 242, interpreting the law to require that the government specifically prove willful intent, on which the jury that convicted the officers had not been instructed.

The good part is that the law has remained in place as a tool for the federal government to take action against police brutality and racially-motivated violence against Black people and others. However, the bad part is that the standard is so high, as prosecutors must prove willful intent on the part of officers, not to mention guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder — who declined to indict Officer Darren Wilson in the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri — wanted changes in the law before he left office.

“You should bring them if you are convinced it’s the right thing to do — and you’re convinced you can win,” Mark Pomerantz, a former New York federal prosecutor told the Star-Tribune. “To bring them and lose them doesn’t serve anyone’s interests.”

This is why so few police officers are held to account for the brutalization of Black people under a civil rights law meant to protect Black people after the Civil War. The law must be changed.