Communities with high economic inequality also tend to have lower upward social mobility. The question is whether there is a causal relationship between the two, as a new study endeavors to answer.

The predominant line of reasoning among economists is that hard times give people the incentive to do what they need to do to climb the economic ladder of success. However, a Brookings Institution study suggests that when young people from the low end of the socioeconomic spectrum succumb to hopelessness — and believe that a middle-class existence is unattainable — they might invest less in their own future.

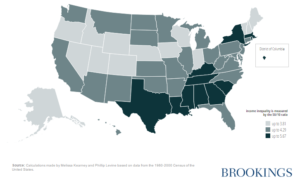

The authors of the study are Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow and University of Maryland economics professor Melissa S. Kearney, and Wellesley economics professor Phillip B. Levine. When examining graduation rates by state, they found that at least one-quarter of students who begin high school in states with high inequality — Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia and Washington, D.C. — fail to graduate in four years, as opposed to 10 percent in the lower inequality states of Vermont, Wisconsin, North Dakota and Nebraska.

Further, low-income youth — especially boys — are 4.1 percentage points more likely to drop out of high school by age 20 if their community is a high-inequality location rather than a low-inequality area.

“Income inequality can negatively affect the perceived returns to investment in education from the perspective of an economically disadvantaged adolescent,” Kearney and Wellesley wrote. “Perceptions beget perceptions.”

“Specifically, we posit that greater levels of income inequality could lead low-income youth to perceive a lower return to investment in their own human capital. Such an effect would offset any potential ‘aspirational’ effect coming from higher educational wage premiums,” they add.

The Brookings research examined income inequality among people in the lower half of the spectrum. The authors found that the focus on “lower-tail” inequality is more meaningful in the lives of poor young people, given that the middle is a more realistic goal at achievement.

Social mobility is a topic of great concern these days, as moving upward on the economic ladder is more difficult in the U.S. than in just about any other advanced, industrialized nation. Further, Kearney and Levine point out that while mobility has not changed much in America and has remained stagnant, income inequality has increased — not because the bottom is falling farther behind people in the middle, but rather because people at the top of the distribution are leaping ahead and away from the middle.

There are a number of possible factors that the authors examine for this relationship, including “differences in educational inputs, poverty rates, demographic composition, and other factors.” They conclude there is something going on, a sense of what they call “economic despair” that has teens making educational decisions based on the perceived returns, and the sense that success is unlikely because there is such a steep mountain to climb.

Further, and paradoxically, the survey results found that for low-income students in states with high economic inequality, academic performance does not play as much of a role in dropping out of school. In the least unequal states, 51 percent of dropouts said they dropped out because of poor performance, as opposed to only 21 percent in the most unequal states.

Brookings cites other research indicating that while nearly all 9th graders want to go to college, by the 11th grade, students of low socioeconomic status are significantly less likely to plan to enroll in college, even when their test scores are high.

“There are important policy implications for what types of programs are needed to improve the economic trajectory of children from low-SES backgrounds,” they write. “Successful interventions would focus on giving low income youth reasons to believe they have the opportunity to succeed. Such interventions could focus on expanded opportunities that would improve the actual return to staying in school, but they could also focus on improving perceptions by giving low-income students a reason to believe they can be the ‘college-going type.'”

Potential forms of intervention include mentor and early childhood parenting programs, and community initiatives that help to instill high expectations and positive behavior in young people, build self esteem, and provide a road map to graduation.

For Black youth who live in communities of high inequality, low aspirations and high despair, these findings are very relevant. Consider the reality in which many Black young people, particularly young men and boys find themselves. There is a dearth of professional role models, particularly outside of entertainment and sports. The underfunded, over-policed educational system in communities of color often serves as a school-to-prison pipeline, with students made to feel criminalized by cops and metal detectors. The school buildings look like prisons, and the dilapidated conditions of the physical structures make Black teens feel unwanted, as the ceiling of opportunity and expectations is as tangible as the school ceiling crumbling from up above.

When the community and society do not care about the well-being of these children, and place little to no hope in their potential for greater heights, what else can we expect? Because they do not see bigger and better things in their neighborhood, because they witness their friends and family going to prison or getting killed, with jail as a rite of passage, how can Black youth achieve if we give them nothing to work with?