Are you sick of racism on the job, or from the police, or in other areas of daily life? If you are Black in America, there is the greatest chance that discrimination is stressing you out and making you sick.

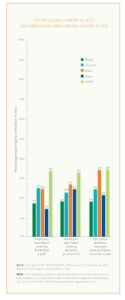

A study released by the American Psychological Association, based on a survey of 3,361 adults conducted by Harris Poll, found that almost seven in 10 adults have experienced discrimination. Further, 61 percent said they endure day-to-day discrimination, of which examples include being harassed or threatened, being treated disrespectfully or receiving poorer service than other people. And nearly 47 percent of adults reported experiencing major forms of discrimination, such as being passed over for a promotion, unfair treatment at the doctor’s office or police harassment. Across groups, employment discrimination was the most commonly reported experience.

American Psychological Association

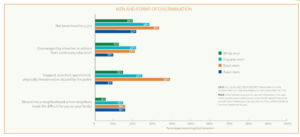

African-Americans are most likely to say they have experienced discrimination, with more than three in four Black adults reporting day-to-day discrimination, and two in five Black men saying they have been searched, abused or otherwise mistreated by the police. And Black, Asian, Latino and American Indian/Alaska native adults all responded that race is the main reason for the discrimination they have faced.

American Psychological Association

And even before people experience discrimination, just the anticipation itself is stressful. Three in 10 Latino and Black adults who experience discrimination once a week or more say they must be very careful about their appearance to avoid harassment or get good service.

“This heightened state of vigilance among those experiencing discrimination also includes trying to prepare for insults from others before leaving home and taking care of what they say and how they say it,” the report said.

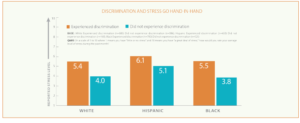

Among those people who report experiencing discrimination, average stress levels for people who report discrimination are higher for those who do not report any discrimination. On a 10-point scale — where 1 is “little or no stress” and 10 is “a great deal of stress,” this translates to 6.1 vs. 5.1 for Latinos; 5.5 vs. 3.8 for Blacks; and 5.4 vs. 4.0 for whites.

“What we found was there clearly was a link between discrimination and stress,” Jaime Diaz-Granados, APA’s executive director for education told USA Today. “It went across all groups. We found that those folks who reported discrimination reported a higher level of stress as well as poor health as compared to cohorts in the same group that reported not experiencing discrimination.”

The Stress in America survey also pointed to significant disparities in how people experience stress, suggesting that stress may also be linked to other health disparities. For example, certain demographic groups have higher stress levels, such as young people, women, adults with disabilities, and LGBT people. Hispanic adults have the highest stress levels. Moreover, 23 percent of adults who rate their health as “fair” or “poor” have a higher level of stress than those who report “very good” or “excellent” health.

American Psychological Association

“Stress takes a toll on our health, and nearly one-quarter of all adults say they don’t always have access to the health care they need,” said Cynthia Belar, Ph.D., APA’s interim chief executive officer. “In particular, Hispanics — who reported the highest stress levels — were more likely to say they can’t access a non-emergency doctor when they need one. This year’s survey shows that certain subsets of our population are less healthy than others and are not receiving the same level of care as adults in general. This is an issue that must be addressed.”

According to the APA survey, since 2007, money (67 percent in 2015) and work (65 percent) have been the top two sources of significant stress. This year, family responsibilities were the third most prevalent stressor for the first time (54 percent), followed by personal health concerns (51 percent), health problems affecting one’s family (50 percent), and the economy (50 percent).

The link between racism, stress and health has been established in other studies. In 2014, researchers from the University of Maryland, College Park found that racism makes people age faster by shortening the DNA biomarkers known as leukocyte telomere length. The shortening of telomeres reflects wear and tear on the body that can be influenced by stress, and can lead to a greater risk of early death and illnesses such as dementia, stroke, heart disease and diabetes.

“Our findings suggest that racism literally makes people old,” said David H. Chae, professor of epidemiology at UMCP’s School of Public Health, as reported by the Baltimore Sun. “Those who have internalized an anti-black bias may be less able to cope with racist experiences, which may result in greater stress and shorter telomeres,” Chae added.