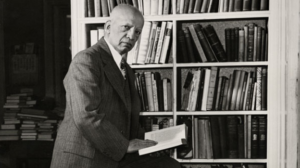

Carter G. Woodson, the ‘Father of Black History’

In Washington D.C., a humble three-story Victorian resting on the corner of 9th Street and Marietta Place, once the home of history-making author and historian Carter G. Woodson, is being turned into a museum. For nearly 30 years, the building served as the home and working headquarters for the man who became known as the “Father of Black History.” Not far from his home, a bronze sculpture of Woodson and a park have been dedicated to his legacy.

Nearly 600 miles away, in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Chicago, Woodson’s legacy is receiving entirely different treatment. An old library named in his honor is barely standing. The community is demanding that action be taken to save the library that houses a historic collection of Black literature. The building is quite literally falling apart, and nothing is being done to rectify it. The Carter G. Woodson Regional Library is being held up by scaffolding.

“You wouldn’t know that is was a library, that it was this incredible resource. This cultural center — museum, if you will,” Melvin Thompson told WGN.

Thompson is the executive director of the Endeleo Institute, a non-profit organization dedicated to building up the Washington Heights community. He isn’t exaggerating. The library is home to the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature, the largest collection of Black literature in the Midwest.

Named after Chicago’s first Black librarian, the collection features slave and genealogy records, historical periodicals, archival documents, reels of microfilm and original manuscripts from notable Black authors. Collecting these items was a passion for Harsh, who was inspired by her participation in the Black history organization started by Woodson. Harsh traveled throughout the South to find works about African-Americans during her years as director of the famous George Cleveland Hall Library. She also organized community programs for the library that brought in literary figures like Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes and Gwendolyn Brooks.

Harsh’s collection isn’t the only piece of the Woodson Regional Library with some age on it. The library is 40 years old, and the scaffolding supporting the entire front of the building’s structure has been in place for 14 years. The city of Chicago says that the poor design and construction of the library necessitated the scaffolding that is now protecting pedestrians from the safety hazard the building poses.

Vivian G. Harsh, Chicago’s first Black librarian

The fragile state of the Woodson Regional Library tells a story of neglect by the city. Thompson and the Endeleo Institute are spearheading a campaign to get the library the attention it so desperately needs.

“We just think that it’s deplorable that the city has neglected this library to the point that it’s in disrepair and unsafe,” Thompson said.

Sadder still is the fact that the neglected library was named in honor of Woodson, who is recognized as the founder of Black History Month. Woodson, the son of formerly enslaved people, was the second Black person to graduate with a Ph.D. from Harvard (after W.E.B. Du Bois). The late scholar and historian co-founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915. Their mission, in Woodson’s own words, was “to collect the records of the Negro and to treat them scientifically, in order that the race may not become a negligible factor in the thought of the world.”

Woodson felt a call to action in a reality where Black culture and individuality were arrested by the oppression of slavery and racism.

“The past of the Negro race has been so obscured and belittled by propagandists, that little is known of the creditable record of the race,” Woodson explained in a 1938 NBC radio program.

The ASALH fostered a sort of revolution that used history to paint a truer representation of African-Americans than what was presented in the films and textbooks of that time. The association published magazines, produced texts for schools and colleges, directed African-American research studies and held conferences, among other things. It effectively helped change not only how the country saw Black people but how Black people saw themselves. In 1926, Woodson founded Negro History Week, which was expanded into Black History Month in 1976.

Woodson worked tirelessly to ensure that the contributions of African-Americans were recognized, celebrated and remembered. Now, the regional library that bears his name and the extensive collection of Black history housed there are all but forgotten by the city of Chicago — an ironic and troubling turn of events. The Woodson Regional Library and its priceless contents deserve to be actively funded, preserved and protected the way its eponym always dreamed.

According to Thompson, every month 25,000 people visit the library and 8,000 books are checked out. These numbers indicate high interest in the services and content provided by the library and underscore the value of such a resource, at a time when national focus is fixed on African-American history and culture.

The long string of publicized police violence against Black citizens; racially motivated aggressive behavior engendered by presidential hopeful Donald Trump among his supporters; and angry protests against the expression of pro-Black sentiments threaten to push the nation back into the oppressive, segregated state that so many historical leaders like Woodson worked to change.

For this reason, it is all the more important to acknowledge and preserve Black history. If the country is to find real solutions to the systemic and overt racial woes that continue to plague it, it is crucial to have resources like the Woodson Regional Library for African-Americans who wish to learn about their people, and for all other races who must be educated on this vital part of American history.

The Endeleo Institute has been pressing the city of Chicago to maintain the Woodson Regional Library since 2013 — with few results, despite the fact that there is, at least in word, a city project underway to restore the library. The project is being managed by Chicago’s Fleet and Facility Management (2FM) and Chicago Public Library.

Meanwhile, state-of-the-art libraries have sprung up in the Beverly and Chinatown neighborhoods of the city. According to the Chicago Public Library website, the Beverly Branch, built in 2009, boasts “cathedral ceilings and clerestory windows.” The Chinatown Branch, opened just last summer, includes a “living” roof with Feng-Shui interior design. The appalling negligence of the city toward an important Black historical resource highlights the greater institutional racism that pervades Chicago government.

At a recent community meeting for the Woodson library project, both 2FM and Chicago Public Library were no-shows. The state of Illinois has granted nearly $10 million to Chicago Public Library for the Woodson project. Only $6 million has been paid out. The remaining funds are held up in a state budget stalemate. According to WGN, the city has plans to put the project up for bid at the end of the month.

When the project is finally launched, it will be a long overdue chance for the city to rectify the years of neglect that has allowed this cultural and historical resource to slip into ruin. It’s an opportunity to restore integrity to the building that houses important pieces of African-American history that the father of Black history, whose name boldly adorns the building, dedicated his entire life to preserving.