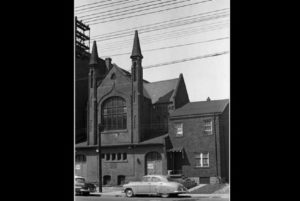

The British Methodist Episcopal church on Chestnut Street, as seen in 1953, around the time the dwindling congregation moved to Shaw Street. (J.V. SALMON)

The recent discovery of the British Methodist Episcopal Church — once the center of Black religious and political life in Toronto for over 100 years — is a reminder that Black history in Canada is also Black history in the United States.

As the Toronto Star reported, the church — formerly part of the U.S.-based African Methodist Episcopal Church denomination founded in Philadelphia in 1794 with Mother Bethel AME — was founded in 1845 by a small group of African-Americans living in Toronto. Several Black families had pooled their money to buy the $55.70 tract of land on Chestnut Street. The institution became a center of the abolition movement, as Frederick Douglass likely spoke to the congregation, which welcomed Black refugees fleeing slavery and state-sponsored terrorism “down South” via the Underground Railroad.

This was a refugee crisis of America’s creation. Britain had abolished slavery in 1833, and Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion led to a violent crackdown on Black people in Virginia, which prompted an exodus of enslaved Blacks into Canada by way of the Underground Railroad. In 1856, however, the Canadian AME ministers split from the mother church in the U.S. and renamed themselves the British Methodist Episcopal. The church wanted to align itself with Britain, which had abolished slavery. In addition, with the increase in kidnappings by bounty hunters looking for enslaved fugitives, the church wanted to ensure the safety of Canadian ministers who traveled to the states for conferences. The congregation moved locations in the 1980s, and the church was demolished to make way for a parking lot, its legacy forgotten and lost to ashes and rubble until last fall. The BME church of 200 congregants currently meets in a former Anglican church.

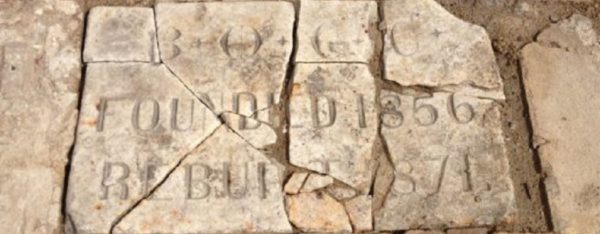

Foundations of British Methodist Episcopal Church of Toronto, the original site on Chestnut Street, uncovered during recent excavation in preparation for a new courthouse. Photos courtesy of Timmins Martelle Heritage Consultants Inc.

Hundreds of thousands of artifacts have been discovered on the site, which has been described by the Star as “one of the largest urban archaeological digs in North America” and “one of the most important blocks of black history in Toronto.” Items such as clothing, toys, tools and ceramics — even the church’s stone foundation and a basement which may have been used as a baptismal pool — provide a window into Black life from another era.

“We have to remember that many of us came [to Canada] because of the problems we had down south,” William Osborne, a retired BME minister who heads the church archives committee, told the Star. “I don’t think we have a proper record of our standing in the city.” The historic church assisted refugees with housing and jobs, and was a focal point for activism around racial injustice.

Given that a new provincial courthouse is being built on the site beginning next year, there is a realization that this heritage site must be preserved and commemorated.

Meanwhile, this year is the 20th anniversary of Black History Month in Canada, as Modupe Babatunde wrote in the Barrie Examiner, providing a timely opportunity to study the genesis of Black settlements in Ontario. Black people fleeing slavery from the U.S. used the long and dangerous journey along the Underground Railroad to make their way to freedom in Canada. After 1793, when Ontario — then called Upper Canada —passed the Upper Canada Abolition Act, Canada became a sanctuary for African-American refugees. Under the law, any child born of an enslaved mother would be free at age 25. Further, Upper Canada was the first territory to pass an anti-slavery act, which made enslaved refuges automatically free when they set foot in Ontario.

Along the Underground Railroad, Black people fleeing slavery in America were helped and guided by so-called conductors such as Harriet Tubman and Josiah Henson, and other Black and white abolitionists, many of whom were Quakers and Methodists. Typically, liberated Blacks who fled to Canada became laborers and railway workers upon arrival.

“It’s so unfortunate that even in school we hardly ever discuss this,” Blair Newby, director of the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Museum, told the Examiner. “American history covers a small extent of it, but we never mention that there was slavery in Canada before it was a haven, or that there was ever discrimination here.”

Newby noted that from the 1840s to the 1870s there were Black professionals, including doctors, lawyers and others, a chapter of Canadian history that has remained hidden.

The 1871 cornerstone of the British Methodist Episcopal Church on Chestnut St. Originally on the outside of the church, it was relocated to the basement floor after the Chinese United Church acquired the site in the 1950s. (Toronto Star)