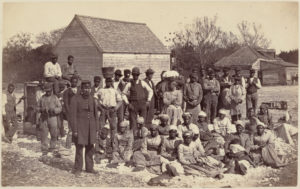

The enslaved people of General Thomas F. Drayton, 1862 © Henry P. Moore

A group of lawmakers has introduced legislation to recognize the 400 years of Africans in America. In a nation whose citizens do not know their history–where Black people know little of their millennia of existence before slavery, and whites know absolutely nothing about Black people aside from negative media imagery—this legislation is significant and something we must examine carefully.

The legislation, named the 400 Years of African-American History Act, is sponsored by U.S. Senators Tim Kaine and Mark Warner, Congressmen Bobby Scott, Don Beyer and Congressional Black Caucus Chair G.K. Butterfield, as WVEC reported. Co-sponsors of the legislation include Congressmen Randy Forbes and Scott Rigell of Virginia, and civil rights veteran Congressman John Lewis, with support from the NAACP and the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

The act would establish a commission to plan activities and programs in 2019, coinciding with the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Africans in America. Further, the commission would focus on the resilience and contribution of African-Americans, and acknowledge the pain and harm caused by slavery and racial discrimination.

“One of the things that I always stress in my classes… is that African-American history is American history,” Asst. Prof. Andrew W. Kahrl, who teaches African-American studies and history at the University of Virginia, told the Cavalier Daily. “This is not something that is some sort of an addendum or something that is separate and apart from what we traditionally think of as so called ‘American history.’”

The legislation is similar to others that have established commissions for English and Hispanic heritage, the 400th anniversary of Jamestown, Virginia and the 450th anniversary of St. Augustine, Florida. “If English lives matter, if Latino lives matter, then African-American lives matter, and they mattered every day since the landing” of the first Africans in America, Sen. Kaine said at a press conference, adding that the country would be “unrecognizable and much the poorer” without the contributions of African-Americans. “The story has a lot of pain to it, but it’s a story that has to be told to commemorate that we as a nation – had it not been for 400 years of African-American history – would be absolutely unrecognizable. What we hope to do with this bill is engage in something we should do to tell the story in a different way than it may have been told 50 to 100 years ago,” Kaine added.

“It’s a story that we need to continue to talk about, study and frankly get better at,” Sen. Warner said. “And I can’t think of a better opportunity than creating a federal national commission that would focus from both the [historical perspective], but equally important, looking forward about how we create a more perfect union that includes all Americans.”

“The commission established by this legislation will play a key role in recognizing, understanding, and celebrating the resilience and contributions of African-Americans in the history of our nation,” said Hilary Shelton, director of the NAACP Washington Bureau, noting the commission would also create an opportunity to discuss the growing influence of Black people in American life.

At a time when America is struggling with the racial sins of the past and present, it is impossible to set things right unless we know what actually happened. How does a nation heal itself if it fails to acknowledge who was hurt and who inflicted the damage, or is even unaware that the damage was done?

Rob Sigler wrote in the Oxford Eagle, a book of interviews with former enslaved Africans written during the Great Depression, as part of the Federal Writers Project, a division of the Works Project Administration of President Roosevelt’s New Deal program. At the time, the emancipated enslaved people of the prior century were dying out, and their oral histories were to be recorded and preserved for generations to come. Oral histories from around the South were published by the FWP in Washington, DC, and each state and county had at least one historian to record and transcribe the interviews and send them to the Library of Congress. “Due to the nature of some of the interviews, they were suppressed and filed away in the basement of the Archives building. When the various states volumes were printed, Mississippi had fewer interviews than many of the states. It was not until the 1970s the balance of the interviews were bundled up and sent to Washington,” Sigler said.

…[One] of the former slaves that was interviewed was Jane McLeod Wilburn. She had been born a slave near Lafayette Springs, east of Oxford. Her first owner was a man named Scrivener, who later moved to Oxford and Jane Wilburn came with the family. Later Angus MeLeod purchased her mother, three siblings and herself. He gave Jane to his wife Betsy.

She was to help with the house and be a nurse to the McLeod children. Miss Betsy taught her to read but she tried and failed to learn to write. She related to the interviewer that it was just fine with her that she never learned to write. As she stated, she might have ended up in “de pen” just like some other folks.

And as Steven J. Niven of The Root reported, this Slave Narrative Project provided compelling accounts of what Black people faced during their enslavement and struggle for liberation. One example is a Civil War-era letter written by Spotswood Rice–a soldier in the 67th Regiment of the United States Colored Infantry who had escaped from the plantation –to Kittey Diggs, the white woman who still owned his children. Rice wrote the letter from an Army barracks hospital bed near St. Louis:

I received a letter … telling me that you say I tried to steal, to plunder my child away from you. Now I want you to understand that Mary is my child and she is a God-given right of my own. You may hold on to her as long as you can, but I want you to remember this one thing: that the longer you keep my child from me, the longer you will have to burn in hell, and the quicker you will get there …

I want you to understand, Kittey Diggs, that wherever you and I meet, we are enemies to each other. I offered once to pay you forty dollars for my own child, but I am glad now that you did not accept it. Just hold on now as long as you can and the worse it will be for you. Never in your life did you give [my] children anything … not even a dollar’s worth of expenses. Now you call my children your property. My children [are] my own and I expect to get them.

There are many untold stories from the 400-year legacy of Black folks in America. Lest we conclude that slavery is merely ancient history with no connection to the present, it is important to reclaim this legacy and retell all its troubling, unsettling details, so that we may understand its impact on present day realities. If those who fail to learn from the lessons of history are condemned to repeat that history, then America has much to learn when it comes to its Black heritage and what it has done to African people on these shores.