The major takeaway from the study by Pew Research Center, which examines economic trends from 1971 until today, is that the middle class is shrinking. This is something which the public has known and felt for quite some time, and now the data proves it.

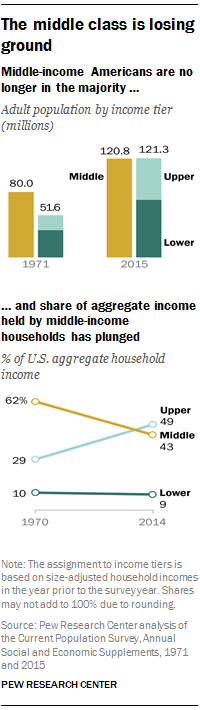

According to the report, after four decades of comprising the majority of Americans, the American middle class is now outnumbered by a combination of poor and wealthier households. As of early 2015, there were 120.8 million adults in middle-income households, as opposed to 121.3 million in the lower- and upper-income category, providing evidence of a tipping point in demographic changes, based on Pew’s analysis of government data.

During the more than forty year period, “the share of American adults living in middle-income households has fallen from 61% in 1971 to 50% in 2015. The share living in the upper-income tier rose from 14% to 21% over the same period. Meanwhile, the share in the lower-income tier increased from 25% to 29%,” according to Pew.

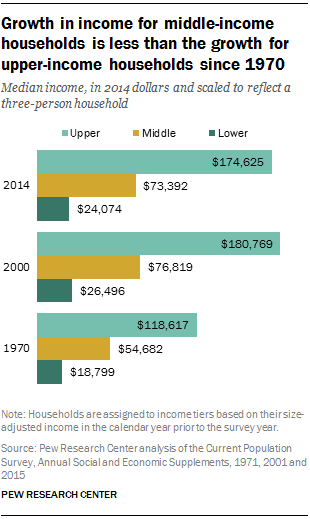

In addition, the wealthiest Americans have experienced a considerable increase in their share of the nation’s income. Middle-income people saw their share drop precipitously from 62 percent to 43 percent. Further, middle-income Americans are falling further down the ladder in the twenty-first century, with median income dropping 4 percent since 2000, and median wealth falling 28 percent from 2001 to 2013 due to the Great Recession of 2007-09.

“Among racial and ethnic groups, blacks and whites came out winners, but Hispanics slipped down the ladder,” the report said.

As for Black households, the news is mixed, and discouraging in the long-term. The Pew report found that Black adults experienced the largest long-term income increase among all demographic groups, and were the only racial group to witness a decline in their share of lower-income people. However, the study determined that African-Americans are substantially more likely to be lower-income, and less likely to emerge in the middle- or higher-income bracket. Over the four-and-a-half decades, Black lower-income households fell from 48 percent to 43 percent, as upper-income households increased from 5 percent to 12 percent.

For decades, Black unemployment has been double the white rate, as employers will not interview people with Black-sounding names, and whites with a criminal record and no college have better employment prospects than college-educated Blacks with a clean record. Banks and other financial institutions have redlined Black neighborhoods for years, blocking them from access to capital and loans that would build their businesses, homes and communities. Further, white vulture capitalists reserve predatory mortgages with high rates for Black and Latino households, a factor which led to the historic decimation of Black wealth since the Great Recession. Although the hollowing out of the American middle class is taking place, Black families have had it even harder. Despite the gains made over the years, Black people have come from a lower point, and struggle as economic racism continues to stifle their progress.

As the Black community prepares to celebrate Kwanzaa this month, it is an opportune time to consider the Nguzo Saba, or the Seven Principles, including unity, self-determination, collective work and responsibility, cooperative economics, purpose, creativity and faith.

If we fail to adhere to these noble concepts, Black America will find itself in the same predicament in another four decades, as we progress one step forward and move two steps backward.